Open-Community-Collaborative Data for Land Rights and Tenure

Posted: March 25th, 2014 | Author: mikel | Filed under: events, talks | Leave a comment »Presenting today at 2014 Land and Poverty Conference

Open-Community-Collaborative Data for Land Rights and Tenure

The generation, management, and distribution of land tenure and land rights spatial data is generally restricted in traditional closed information architectures, in part for legitimate legal and security reasons. However, the gap thus far in adoption of more innovative open data practices means a missed opportunity to address critical issues of accountability and access to land rights data for the most marginalized. Open data communities, such as the OpenStreetMap (OSM) project, have proven to be transformational collaboration platforms in domains like disaster response, and now several projects show promise for this open approach to land rights. This paper explores two distinct kinds of contribution from the OSM approach. Firstly examined is the direct use of OSM as a core engagement activity for advocacy, planning, and accountability by communities asserting their rights for representation and security. Lessons from projects in Kibera, Indonesia, East Jerusalem, and La Boquilla, Columbia are detailed. Secondly, OSM is looked at as a starting technical software base & community model for collaborative, open geographic data creation & sharing, forked (in the open source sense) for adaptation to the particular access rules and data structures required for land tenure registration.

OpenStreetMap is a free and open map database of the entire world, build from the active collaboration of tens of thousands of volunteers globally. It is sometimes called the “Wikipedia of Maps”, since contributing to OSM is open to absolutely everyone, and the data and code ecosystem are all in the commons, licensed for re-use and re-distribution. Such “crowd-sourced” initiatives have been held up to intense scrutiny, and have been found to meet or exceed the data quality of traditional sources, and are certainly more accessible. Thus, OSM has been adopted by companies, governments, universities, international organizations, and software developers. The domain of disaster response, particularly through the work of the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT), has been transformed by the practice of OSM, after the devastating 2010 Haiti earthquake, where OSM became the base map for the response. More recently, Typhoon Haiyan saw over 1000 contributors map millions of features and damage point, for use by organizations such as the American Red Cross, UNOCHA, MSF, the World Bank, and the New York Times.

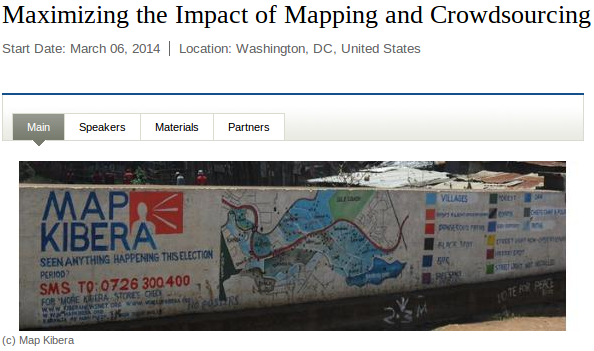

In the first part, community mapping in OSM has proven a valuable supplement to official tenure process, or to help communities advance their rights agenda. A core principal of OSM is that the most accurate map will be made, with the right basic training, by people residing in a location, not necessarily survey and cartographic experts. This especially holds true in communities at risk of dispossession by authorities, where official maps may portray a geographic mis-reality more conducive to their plans, or the community itself may not be physically accessible and suspicious of outsiders. Take the Kibera slum of Nairobi, the object of many controversial upgrading and resettlement plans, was a blank spot on official maps, until the public infrastructure (including roads and paths, sanitation infrastructure, health services, etc) was mapped by Map Kibera in OSM. This project (and now organization) taught young residents the technology to make the map themselves, and represent their community. Being a completely open system, the goal was not to map private residences, but to make visible the community as a whole, and of particular interest here, track the events and reactions to upgrading programs. Spatial data is used as the context for citizen media, in the form of bloggers and videographers, who geolocate stories on the Voice of Kibera, an instance of the Ushahidi platform. Stories have covered demolitions in Soweto East, resettlement to the “decanting site”, and most recently efforts for the Nubian community (the original settlers of the slum) to gain title and recognition. The community, evidence based perspective, linked to specific locations, shared openly, both online and offline, has provided a much needed monitoring and accountability function in these contentious processes.

Another example is found in Indonesia, where HOT undertook a wide ranging effort to collect data in OSM for disaster preparedness risk models. This project involved training and connections with a large number of actors, from disaster preparedness agencies of the Indonesian government, to university students, to city officials, planting the seed of an open data community in Indonesia. As is often the case with open data, unexpected uses and connection arose, specifically with the ACCESS civil society strengthening program. Part of ACCESS activities involved “poverty mapping”, participatory mapping of community infrastructure and socio-economic data, a step to create community development plans. These poverty maps were created on paper in a facilitated process, and while quite detailed, beautiful and useful, the opportunity for re-use, analysis, and access to these maps were limited. HOT adapted the OSM workflow to these participatory processes, which allowed for better and easier data collection, and connection into a host of open source tools to visualize and analyse that data. A major change to OSM tools was made to handle private and secure data. While communities were comfortable sharing openly geographic data on community infrastructure, they did not want to share detailed socio-economic information. To accommodate that, the OSM editing tools were adapted to work with multiple databases, both the open, public database, as well as private database. This provides a means to selectively share community data, without invoking another tool.

In the second part, OSM is examined as both a technical and community starting point to open creation and sharing of tenure data. It’s entirely fair to say that OSM has been the most successful approach to collaborative geographic data ever. That’s due to some key decisions of the architecture, such as flexible tagging rather than rigid ontology, and transparent history of individual contributors. The software ecosystem is quite robust, including what might be the most user friendly map editing client developed, iD. The community approach is decentralized, distributed responsibility, yet quite unified through clear purpose. However, not all kinds of data are appropriate for OSM, as OSM focuses on visible infrastructure, land use, and some administrative boundaries, but by community convention, does not contain cadastre (among many other things). As well, OSM is completely open for anyone to edit, and that is simply not possible for land tenure data; there must be some process for validation and protection of submissions. There are other projects that have started with OSM architecture and principals, and adapted to a different database. For instance the USGS prototyped its use for the National Map; the Moabi project is deploying OSM architecture for collaboration on natural resource extraction data; and the before mentioned poverty mapping project in Indonesia. In order to support approaches like the Social Tenure Domain Model, there are very particular adaptation requirements to OSM. Access control to both data editing and data structures is required, and experiments show that OSM architecture is amenable to such changes. Just as crucial, OSM makes individual contributors visible, and relies on their participation, communication and collaboration. Despite the necessary institutional element of land tenure, a successful program must retain such individual empowerment.

Challenges of OpenStreetMap in Institutions

Posted: March 4th, 2014 | Author: mikel | Filed under: openstreetmap | Leave a comment »This Thursday, the World Bank will hold an event on how large organizations can better engage with projects that involve OpenStreetMap. That’s my take anyway! I’ll be part of a panel with good folks like Nithya Raman from Transparent Chennai and Rob Baker from, um, everything. I’m hoping this is a good chance to get some strong ideas percolating through the bureaucratic membranes. My slides are here. You should come and maximize with us! (storify stream of the event here)

Ahead of the event, I’m reflecting (rambling?) on what’s been challenging for me to bring OpenStreetMap, citizen journalism, and participatory technologies into the institutional context of large development organizations. This interests me because bringing together “community” and “authoritative” data and approaches will produce better results. I’m coming from the assumption that the methodologies of these tools in community development are pretty sound on their own, and we have good ways to continually improve what we do. The struggle I want to examine is the associated organizational change in large institutions. That’s where the gap in impact lies, not in anything fundamental in the methodologies.

The event came to be after I successfully bugged Stephen Davenport (who’s now at the World Bank) to publish a somewhat forgotten, but proven very useful, Draft HowTo Note on Community Mapping. I regularly included this document in a package to introduce our work to others (as well as the Case Study on Map Kibera and LearnOSM). And I soon learned the HowTo would be an independently published chapter. (It’s published, read it.) And we’d hold an event with smart and influential people (that means you).

Scaling Up? From http://www.flickr.com/photos/wlscience/3071678864/

So we are “maximizing” at the event. Or, let’s make it bigger. I’ve often been asked about scaling up community mapping. Like, it’s great that you mapped one neighborhood, now let’s do the entire city, the entire district, the country, 12 countries. It doesn’t work like that. Communities can’t be “industrialized”, but always take intensive engagement. That doesn’t mean that things can’t “grow” … they can very fast as evidenced by the OpenStreetMap community as a whole. But that networked growth occurs by building relationships at all scales, not simply multiplication. Still, if you want to map the 100 largest slums in the world, I do have a plan, it just won’t be a cookie cutter model.

There’s a big mismatch in time scale. Organizations work on project timelines and annual budget timelines. Notice the substantial increase in projects initiated late in the fiscal year. Projects end when they end. Communities don’t end. A thriving community of mappers takes way more time to develop than a project timeline, and especially with a real physical community, there are relationships and expectations that extend beyond the institutional structure. I don’t have a good answer for this, and I expect to see this completed solved on Thursday ;).

World Bank projects approved by month. Is it just because it’s better to start projects in June? From http://www.chezvoila.com/blog/datadive2

Publications also must deal with time scale mismatch. The original research for the Interactive Community Mapping chapter started about 3 years ago. And the research was excellent, but the conclusions were drawn at that point in the past. Choose another arbitrary point in time, and you get another conclusion. In Kibera, the gap between “need for information” and “government engagement” has closed substantially, and there’s a different story in the balance of “results” and “process oriented” methodologies. Map Kibera Trust has successfully undertaken both modes repeatedly, in many places, engaging community and delivering specific results for a number of partners, including government, most excellently in the 2013 election work. This years-long timeline was actually by design! While there wasn’t a solid results-driver to start, the whole approach was pretty new at that point, and the political climate in Kenya very different. Learning was desired and required, and this needed to play out over the years to be effective.

On the other hand, Ramani Tandale has had a lot of promise and interest, but hasn’t reached that potential yet. Specifically, the original “need for information” was driven by the urban sector of the World Bank, to integrate this work into slum upgrading programs (which were excellent actually). But then the Tech Team Lead in that Tanzania office left, and a number of other schemes didn’t materialize. In other words, the convening role of the World Bank did not have real long term consequence for the community. At least not yet. Despite that, we’ve worked to continue the Tandale project and the people of Tandale have shown incredible interest, such as paying for internet out of their own savings group funds! But they have not received the organizational support, despite the starring role Tandale takes in many World Bank presentations, nor yet the continued solid connection to government to respond to needs. Organizational support and this final connection may be the most difficult piece of the puzzle.

Incentives are super complicated. All of us need to survive, many of us want to contribute something more. It’s a hard balance, and harder still for someone strugggling economically. Ground Truth has had so many different structures in this way. In Tandale, the university students did actually get a stipend for the “industrial training module”, which was paid out of project funds. That’s standard arrangement apparently. True, it didn’t have much correlation with long term interest … the 2 or 3 strongest folks have stuck with it out of their enthusiasm (though they’ve benefited financially too from their continued engagement). That’s natural. It is worth considering that financial incentive operates at all levels; even government officials in many places expect to receive a “per diem” for taking part in a training, or travelling to a conference (especially from the World Bank!). I don’t think you can simply equate presence or absence of financial reward with motivational success.

But clearly there are other benefits. One of the key benefits, and key distinctions of “Interactive Community Mapping” from participatory mapping of the past, is the connection to a global technical commons like OpenStreetMap. Just like OSM has fundamentally changed GIS into a global network, the same goes for participatory GIS. What this means is that data contributed for one purpose, like community engagement, still exists for special purpose mapping, and vice versa. The commons has its own sustainability, and allows for unintended use … the honest reckoning that we don’t know all the potential applications for these maps, but the option is there. It connects community members directly to a global network of mappers, who can share not only data, but share a data community. What “ICM” and “PGIS” do have in common is an acknowledgement that some places are not even accessible to professionals, or that professionals would do a comparatively worse job then people who know a place.

Mappers in Nepal, Mapping for the Philippines. From http://kathmandulivinglabs.org/blog/crisis-in-the-philippineswe-are-with-you/

With a global network structure, new organizational roles are emerging. Some call these infomediaries. There are “local organizations” whose specific mission is to support use of ICT practices in civil society and communities … they work between global technical networks and the needs of local communities. That is what Map Kibera Trust has become. It’s a gap in Tanzania so far. For HOT in Indonesia, there is for all real purposes a “HOT Indonesia” organization, which runs itself and serves this purpose. The groups taking part in GFDRR’s OpenCities fit this role. Many of the groups GroundTruth has worked with (as international ICM “experts”) fit this mold, such as Grassroots Jerusalem and Transparent Chennai. Kenya has a number of these kinds of groups, including Open Data Institute, Mzalendo, Map Kibera, to some extent Ushahidi/iHub, etc.

Some other quick final thoughts, but I think potent ideas for large organizations looking to do community mapping.

With a global network structure, people in large organizations can be directly involved in communities. OpenStreetMap is meant to be easy for anyone to contribute to, and gets easier all the time. Yet, it’s a rare person developing the space for a project inside large organizations that learns to map before designing a project. It’s takes about 30 minutes, and it will make everything a lot more real and easier to talk about.

While we’re at it, can we just stop hedging with “Interactive Community Mapping”, and just talk about OpenStreetMap?! Aside from balloon and kite mapping, which is a different awesome technology, no one is using Google Map Maker seriously for this kind of work. Let’s get on with it and acknowledge, OpenStreetMap is winning, the world needs OpenStreetMap.

And last, asking a favor. Update contracts to reflect open source and open data. The projects I work on are specifically about production for the commons. Yet most contracts still hold intellectual property rights of the work of the contract. This requires further discussion and annexes to standard contracts, every time. I’m sure we can solve this just once.

See you on Thursday!