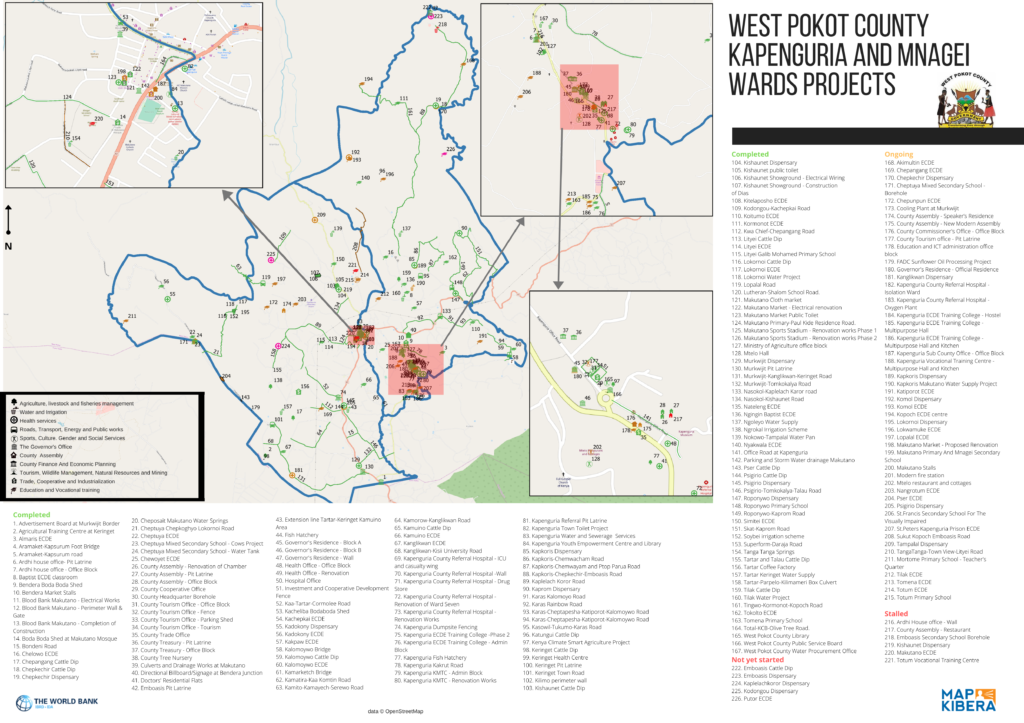

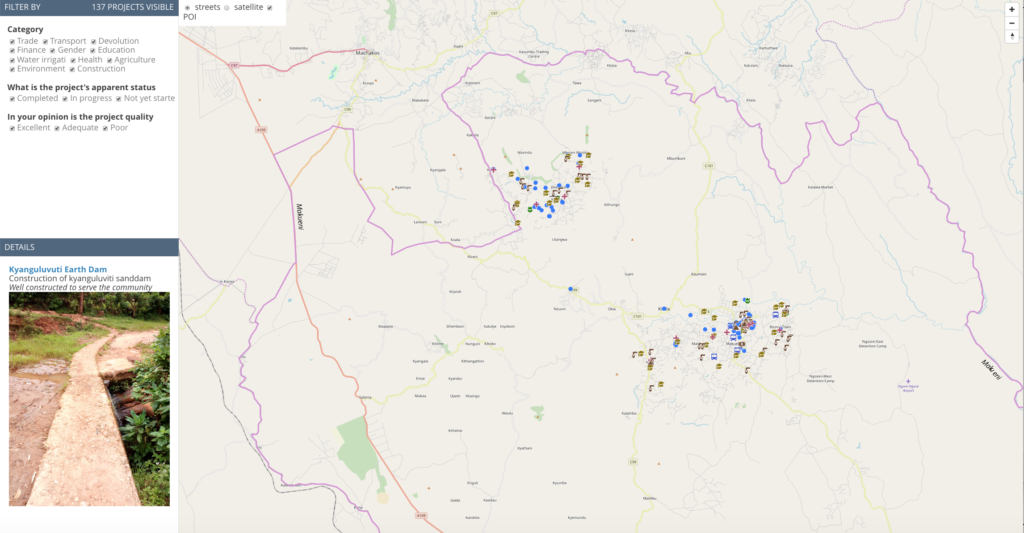

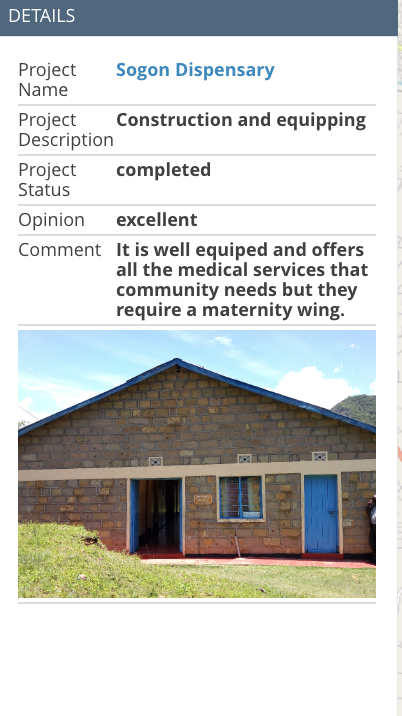

Mapping Participatory Budgeting in Kenya’s Counties

Posted: March 13th, 2020 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Accountability and Transparency, citizen feedback, Citizen Generated Data, Governance, kenya, openstreetmap, OSM, World Bank | Tags: Citizen Generated Data, Counties, Open Data, Participatory Budgeting | Leave a comment »

GroundTruth Initiative has been working for the past two years with three county governments in Kenya, along with partners the World Bank and Map Kibera Trust, to map and gather detailed feedback on county-funded projects. By training both county officials and local youth, while working cross-departmentally on data resources, GroundTruth has helped refine a process for citizen engagement which both increases transparency and accountability and provides much needed data and digital maps for the county.

In 2010, Kenya created a new constitution which focused on devolution of power to 47 new counties. Rather than focus development planning and budgets entirely at the national level, or in sub-regions which encompassed vastly different terrain and needs, the new constitution gave power to local officials and governors in the counties. Along with that came a need for new systems for finance and data. Starting up new processes and linking them to national systems was best done through digital means, but not all counties were ready technologically for these requirements.

In 2015, the World Bank began to support select counties to engage their citizens in a process of participatory budgeting. Citizens gathered in each subsection of the county, down to the village level, and prioritized the greatest needs. Budgeted projects included everything from new hospital wings to small dams and footbridges to new water points and classrooms. The process repeated each year, but it was difficult to track progress on the projects and to know where they were located so as to best allocate resources the following year. There were very few up to date digital or print maps showing county projects or pre-existing social resources and features.

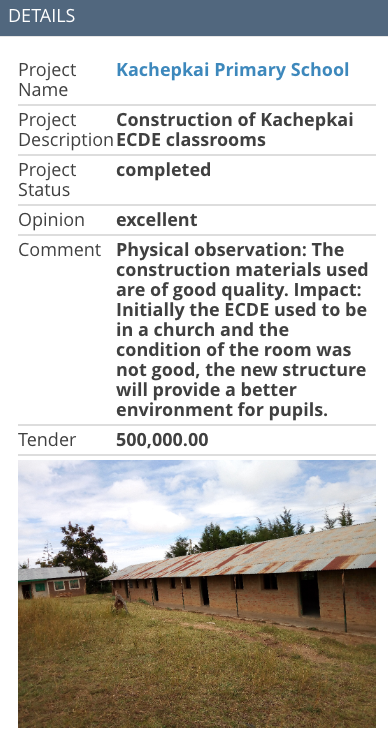

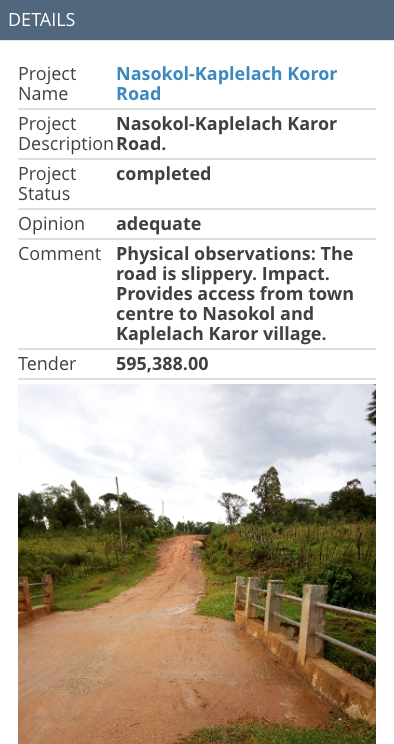

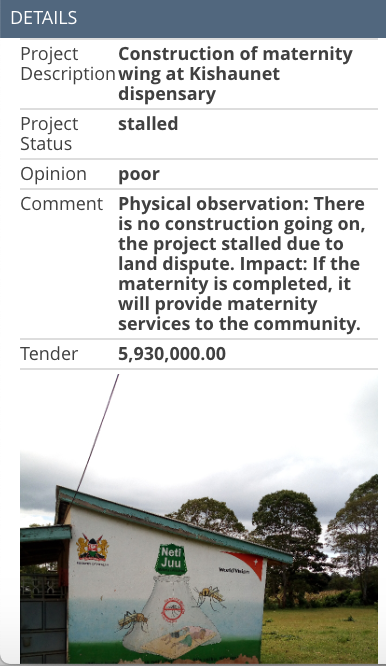

GroundTruth Initiative started working with counties in 2017 to help them create such maps. In partnership with Map Kibera Trust, GT worked with Makueni, Baringo, and West Pokot counties to use OpenStreetMap to develop a base map for their counties and map the county’s projects. As part of the process, county officials from Budgeting, M&E, Lands and Planning, ICT, and other departments were trained to use Open Data Kit and the Kobo Toolbox to survey their territory. In order to carry out the process efficiently and increase citizen involvement and project feedback, youth from each ward were also trained. Together, they not only mapped the project locations and basic details by visiting each project, but also photographed them and took notes on their completion status, operational status, and apparent quality.

This feedback was compiled by GroundTruth on a demonstration website for each county. The maps were also developed into print versions which could be used during the PB meetings themselves, and used and shared by officials who are often more comfortable with printed maps.

The work has paid off, as some counties have now completed a second phase of the project, receiving additional training on how to execute the process themselves and how to work with the data. All the maps and data stored in OpenStreetMap is open; the feedback on the projects is visible through the linked website. The purpose of the maps is to help the counties and the public to be able to track projects and budget expenditure. In the new phase of work completed in December 2019, budgeted contract amounts are also included on the site.

By working closely with both youth and government Data Fellows, Map Kibera and GroundTruth are currently supporting the counties to continue to utilize the process and better integrate it with their finance, M&E and planning departments, and work with their new GIS officers. Meanwhile, other counties are looking to work with the same process. The future of devolved governance and citizen accountability through mapping looks bright.

New Report Published on Sustainability in OpenStreetMap for Development

Posted: March 10th, 2020 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Governance, openstreetmap, OSM, Research, Sustainability, World Bank | Tags: openstreetmap, sustainability | Leave a comment »

A new report, written by GroundTruth director Erica Hagen for the World Bank’s GFDRR (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery), examines sustainability challenges and strategies for the use of OpenStreetMap in developing countries.

Over the past several years, OpenStreetMap (OSM) has been used by an increasing number of aid and development organizations, like the World Bank’s Open Cities initiative, with the aim of supporting a wide variety of development and humanitarian objectives. OSM mapping has taken place in response to natural disasters (like the Haitian and Nepalese earthquakes), in order to empower slum communities (such as Kibera, in Nairobi), to help mitigate or prevent disease outbreaks (Ebola, and Malaria), or simply to promote the use of open map data among government officials and others already using GIS (for example in Kinshasa, DRC).

However, mapping efforts have frequently run into challenges as mappers and data users try to navigate issues of open data and technology to keep data and maps current and impactful. It can be difficult to keep trained volunteer mappers engaged, build and fund mapping organizations, engage governments productively, develop local management capacity, create successful mapping businesses around OSM, to name just a few.

This research explores the many facets of OSM in development and its “sustainabilityâ€. It examines the definition of sustainability, reviews existing literature about sustainability in ICT4D, and identifies four dimensions of “sustained benefit†which can help us to understand factors that will influence longer-term success. The paper identifies seven different kinds of actors which typically work with OSM in developing economies, and their particular challenges, illustrated by several case study examples.

The report then suggests a way forward for funders, practitioners, and others to move toward greater benefits for all given the constraints of OSM globally, the ethical considerations of digital open mapping, and the challenges of open source and open data projects generally as technology matures.

Sustainability in OpenStreetMap: Building a more stable ecosystem in OSM for Development and Humanitarianism

A white paper prepared for the Open Data for Resilience Initiative, GFDRR Labs, World Bank.

Announcing Release of New Map Kibera Research: Open Mapping from the Ground Up

Posted: October 12th, 2017 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Accountability and Transparency, OSM, Research | Leave a comment »Earlier this year, I was fortunate to have the chance to research some of Map Kibera’s work over the past 8 years in the area of citizen accountability and transparency. I was interested especially in whether the maps made in Kibera had had an impact beyond the life of each project, since they were available online on OpenStreetMap and our own website, and distributed offline via paper maps and wall murals. I looked at three sectors we’d worked on —  education, water and sanitation, and security — and interviewed those who had commissioned, been given, or discovered the related maps in some way. I looked particularly at whether citizens had been able to use the maps to improve accountability and governance. This research has now been published as part of the Making All Voices Count Practitioner Research and Learning series.

The results were surprising. I found that maps had been used for a wide variety of purposes which we hadn’t known about before, including arguing for policy changes and reallocating donor resources in Kibera.

The research process involved first trying to track the maps, which was not easy. The Map Kibera team, working with research assistant Adele Manassero, asked around in Kibera, looked on social media, combed through blog posts, and otherwise tried to find out who used our maps and why. Working with open data can be messy this way. We found a number of people who said they had indeed been working with our data. Some were from various NGOs, others were in government. We also followed up on those we’d handed out the map to directly, like school heads and community leaders.

The schools map in particular, which had been the most widely distributed of our maps by far in paper form, had been used for many purposes. It had even been photocopied by the local education official to hand out to visitors. The local Member of Parliament had used it to reach out to the informal schools and create a WhatsApp group to communicate about key school information — Â and to petition Parliament for increased education resources for students in Kibera.

Part of the message here is that by sharing information widely, both digitally and on paper, AND with the backing and network of a trusted local team — Map Kibera — you can make room for impacts beyond a narrow project purpose usually associated with data collection. With all of the emphasis in ICT4D on designing directly for the end user, data collection is usually still done for the end user called the donor — or the organization’s HQ, or governmental higher-ups. Sometimes this data doesn’t even get used. In this case, I found that the better we targeted a variety of local potential “end usersâ€, like leaders of local associations, teachers, and CBOs, the more we saw uptake and impact even without intensive chaperoning of the information. Maps wound up being repurposed. This is the way, I believe, open data is supposed to work.

I suppose then the question is, why did it work this way, when so often it doesn’t? I found that collection and sharing of information by trusted local residents helped lend validity to the information, improve trust and communications between government and citizens, and bring informal sectors into the light in a way that benefitted the community. If anyone wanted to know where the data came from, the folks collecting it were right there, visible, identifiable and relatively unbiased. They could also be called upon to make corrections. Schools indeed have reached out, and recently a lot of updates were made to that data by the team. The analog method of change — being able to call someone, who lives in your neighborhood, and refer to a paper visual — is key to local social impact, even if the information collected is digital.

I’ll be blogging about a number of other things I found interesting out of this research in the weeks to come. Stay tuned!

OSM: Mapping Power to the People?

Posted: June 5th, 2015 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: OSM, tech | Tags: Community, data, future of OSM, power | 2 Comments »As you probably know, OpenStreetMap is a global project to create a shared map of the whole world. A user-created map, that is. Of course, in a project where anyone can add their data, there are many forms this can take, but the fundamental idea allows for local ownership of local maps — a power shift from the historical mapping process. Now, if I want to add that new cafe in my neighborhood to the OSM map, I can do it, and quickly. And I don’t have to worry that I’m giving away my data to a corporate behemoth like Google — open and free means no owner.

But lately I’ve noticed a trend away from the radical potential of such hyperlocal data ownership, as OSM gets more widely used and recognized, inspiring everyone from the White House to the Guardian to get involved in remote mapping (using satellite imagery to trace map details onto OSM, like roads and building outlines). But remote activities still require people who know the area being mapped to add the crucial details, like names of roads and types of buildings. So why is the trend worrying?

Since first training 13 young people in the Kibera slum to map their own community using OSM, in 2009, I have focused quite a bit on questions of the local — where things actually happen. And the global aid and development industry, as anyone can see who has worked very closely with people anywhere from urban slums to rural villages, tends to remain an activity that begins in Washington (or at best, say, Nairobi’s glassy office buildings) and ends where people actually live. Mapping, on the other hand, is an activity that is inherently the other way around — best and most accurately done by residents of a place. And, I would argue, mapping can therefore actually play a role in shifting this locus of decision making.

More poetically perhaps, I also see maps as representations of who made them rather than a place per se. So if the community maps itself, that’s what they see. And that can shift the planning process to highlight something different — local priorities. After all, a resident of a place knows things faster, and better, than any outsider, and new technology can in theory highlight and legitimize this local knowledge. But just as easily, it seems, it can expedite data extraction.

Even more importantly, as any social scientist will tell you, a resident of a place knows the relevant meaning and context of the “facts†that are collected — the story behind the data. An outsider often has no idea what they’re actually looking at, even if it seems apparent. (An illustrative anecdote: I was recently in Dhaka and we noticed a political poster with a tennis racket symbol. We wondered why use a tennis racket to represent this candidate? That’s not a tennis racket — it’s a racket-shaped electric mosquito zapper, said one Bangladeshi. What you think you see is not the reality that counts!)

So, when the process of mapping gets turned around — with outlines done first by remote tracing and locals left to “fill in the blanks†for those outside pre-determined agendas, that sense of prioritization is flipped. In spite of attempts to include local mappers, needs are often focused on the external (usually large multilateral) agency, leaving just a few skilled country residents to add names to features in places they’ve never set foot in before.

There are degrees of local that we are failing to account for. Thinking that once we’ve engaged anyone “local†(ie, non-foreign) in a mapping project we’ve already leveled the playing field is letting ourselves off the hook too easily. By painting the local with one brush we fail to engage people within their own neighborhood (not to mention linguistic, ethnic group or gender). We underestimate the power of negative stereotypes in every city and country against those in the direst straits, including pervasive ideas of lack of ability, tech or otherwise. This is especially problematic when dealing with the complex dynamics of urban slums, in my experience. But any place where we hope to eventually inspire a cadre of local citizen mappers who care about getting the (data) story right, it’s crucial to diversify.

Having dealt with these challenges nearly from day one of Map Kibera, I’m particularly sensitive to the question “How does a map help the people living in the place represented?†You might say that development agencies and governments have a clear aim for their maps that will help in very important ways. Therefore, a faster and more complete map from a technical standpoint is always better. (Indeed, getting support for open maps in the first place is quite an achievement). But more often than you’d think, the map seems to be made for its own sake or to have a quick showpiece.

Even if our answer is that the map would help if disaster struck, that seems to be missing the point and might not even be true in most cases. Strong local engagement and leadership are said to be “best practice†even in cases of disaster response and preparedness, though they aren’t yet the norm. Since the recent earthquake in Nepal, there has been a very successful mapping response thanks to local OSMers Kathmandu Living Labs. But critically, this group had been working hard locally for some time. And we should see this as a great starting point for widespread engagement, not an end product.

Another problem is that established mapping processes in the field aren’t questioned much, even when it comes to OSM. Since mapping is often something people do who are techies of some kind — GIS people, programmers, urban planners — organizers sometimes seem to forget to simplify to the lowest common denominator needed for a project. Does the project really need to use several types of technological tools and collect every building outline? Does every building address need to be mapped? If not, it just seems like an easy win — why not collect everything? One reason not to is because later when you find you need local buy-in, even OSM may be viewed as an outsider project meant to dominate a neighborhood, a city, especially in sensitive neighborhoods where this has indeed been a primary use of maps. I wonder if people will one day want to create “our map†separately from OSM. A different global map wiki which is geared toward self-determination, perhaps? That would be a major loss for the OSM community.

Perhaps I seem stuck on questions of “whose map†and “by whom, for whom?†Well, that’s what intrigued me about OSM in the first place. We used to talk a lot about the democratizing potential of the internet, about wikis and open source as a model for a new kind of non-hierarchical online organizing. Now, it’s clear that because of low capacity and low access, it’s actually pretty easy to bypass the poor, the offline, the unmapped. And because of higher capacity among wealthier professionals and students in national capitals globally, it’s easier for them to do the job of mapping their country instead. Of course there isn’t anything wrong with people coming together digitally over thousands of miles to create a map. In an idealistic sense it’s a beautiful thing.

But the fact is, we (that is, technologists and aid workers — both foreign and not) still tend to privilege our own knowledge and capacity far and away over that of the people we are seeking to help. We can send messages to the poor through a mobile phone, strategize on what poster to put up where, but the survey to figure out who lives there and what they care about? Still done by outsiders, hiring locals only as data extractors. As knowledge and expertise used to make decisions becomes more data-driven and complex, a class of expert and policy maker is created that is even more out of reach. Access has always been messy. Now (thanks in part to mobile phone proliferation and without much further analysis), we hardly talk about access anymore. The fad has shifted to “big data†and other tech uses at the very top.

To me, OSM was always so much more than just a place where people shared data. It was one small way to solve this problem of invisibility bestowed by poverty.

The possibilities of OSM to empower the least powerful are still tantalizingly close on the horizon. With just a few tweaks to existing thinking, I hope we can tip the scale — we can prioritize the truly local and allow the global to serve it. But to do so we must resist glib and lazy thinking around how those processes actually work. We must pay attention to order of operations (who maps first? whose data shows up as default?), and subtleties of ownership and buy-in, and we must examine who we think of as “localâ€.

But most of all, and most simply, we have to reorient our thinking in designing mapping projects. It could be quite straightforward, for instance:

- integrating more localized thinking into training courses and OSM materials, suggesting that people on the margins (such as slumdwellers) can and should be learning OSM tools as well;

- training people to think about social context and local priorities not just technology;

- doing more offline outreach and print map distribution; creating new map renderings highlighting levels of local and remote mapping;

- making it the norm that residents of a neighborhood be involved in early project planning;

- engaging with people who have long done offline forms of data gathering and mapping in their communities.

- Considering that first pass on a blank map might matter.

- And considering that leading local technical mappers start to conceptualize their roles more as mentors to communities and to new mappers in those places than as expert consultants to foreign organizations. I’ve seen the light bulb go on when that happens.

Yes, ultimately, we will do best to address the incentive structures of international funding which are keeping us from achieving what we’d all undoubtedly wish to see, which is everyone getting the opportunity to put themselves on the map.

Many will say that it is just too hard, too time consuming, too cumbersome, too expensive, too — something — to really prioritize local in the way I’m talking about. We’ll never hit “scale†for instance. Something needs to be done now. But I would ask you to reconsider. I believe that in fact, sensitive and thoughtful engagement with communities is the only real path to scale and sustainability for many kinds of “crowd-†or “citizen-†based data work that is now happening, and most certainly the only way to reach the real target of any development-oriented data effort — actual improvements in the lives of the world’s poor and marginalized.

This post also appears here on Medium.