Mapping Participatory Budgeting in Kenya’s Counties

Posted: March 13th, 2020 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Accountability and Transparency, citizen feedback, Citizen Generated Data, Governance, kenya, openstreetmap, OSM, World Bank | Tags: Citizen Generated Data, Counties, Open Data, Participatory Budgeting | Leave a comment »

GroundTruth Initiative has been working for the past two years with three county governments in Kenya, along with partners the World Bank and Map Kibera Trust, to map and gather detailed feedback on county-funded projects. By training both county officials and local youth, while working cross-departmentally on data resources, GroundTruth has helped refine a process for citizen engagement which both increases transparency and accountability and provides much needed data and digital maps for the county.

In 2010, Kenya created a new constitution which focused on devolution of power to 47 new counties. Rather than focus development planning and budgets entirely at the national level, or in sub-regions which encompassed vastly different terrain and needs, the new constitution gave power to local officials and governors in the counties. Along with that came a need for new systems for finance and data. Starting up new processes and linking them to national systems was best done through digital means, but not all counties were ready technologically for these requirements.

In 2015, the World Bank began to support select counties to engage their citizens in a process of participatory budgeting. Citizens gathered in each subsection of the county, down to the village level, and prioritized the greatest needs. Budgeted projects included everything from new hospital wings to small dams and footbridges to new water points and classrooms. The process repeated each year, but it was difficult to track progress on the projects and to know where they were located so as to best allocate resources the following year. There were very few up to date digital or print maps showing county projects or pre-existing social resources and features.

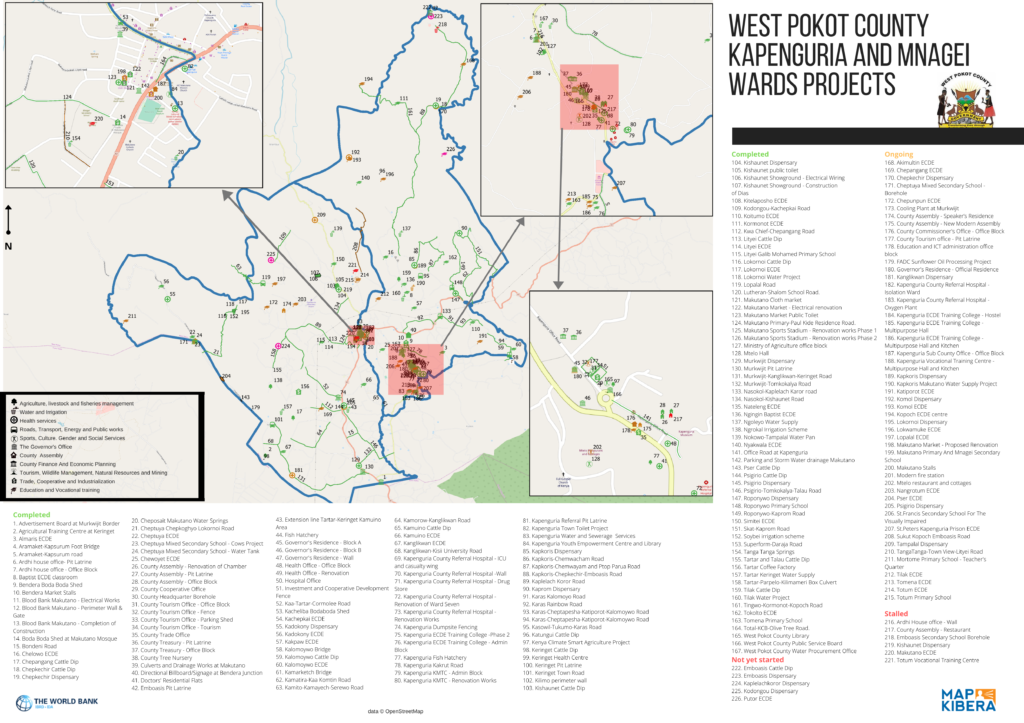

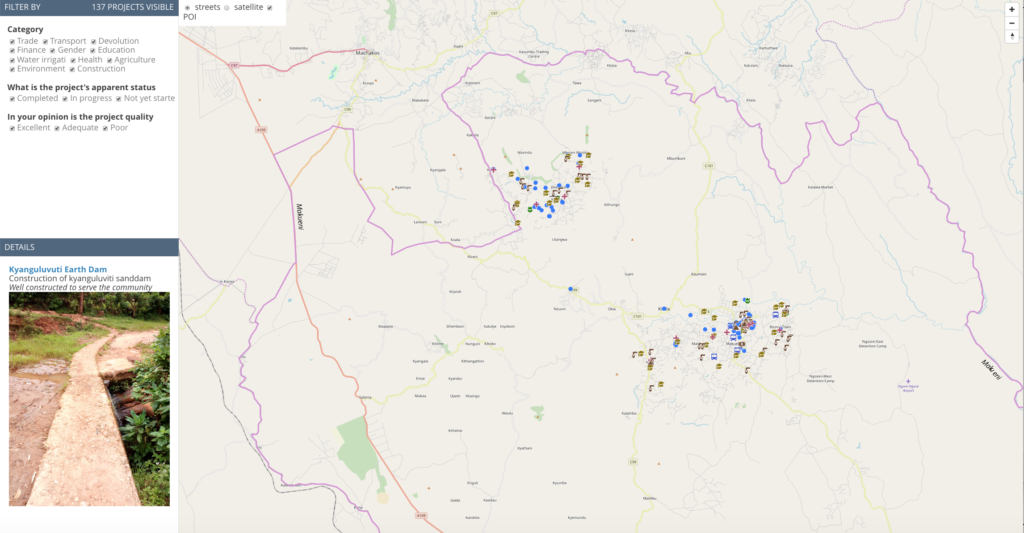

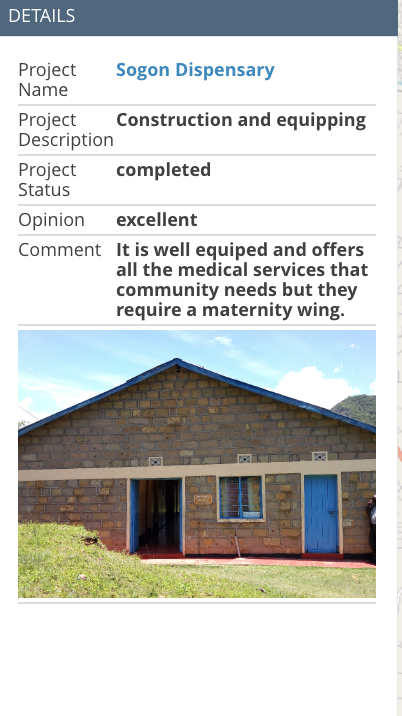

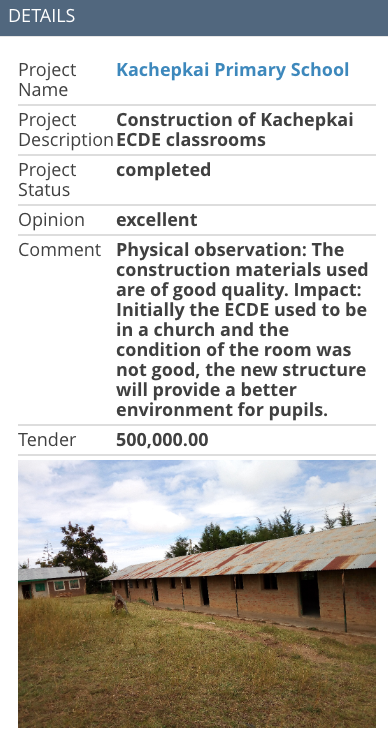

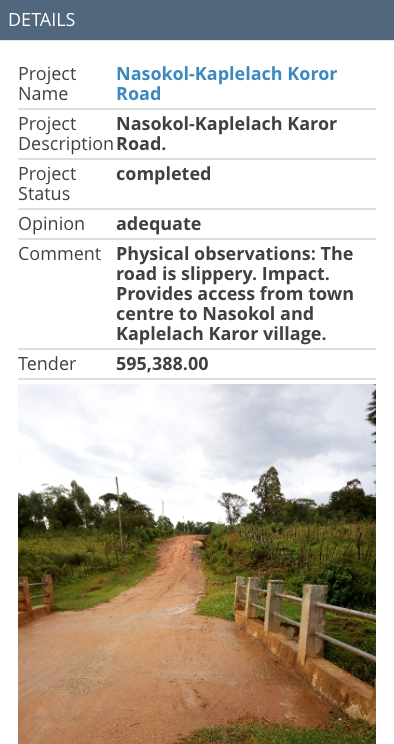

GroundTruth Initiative started working with counties in 2017 to help them create such maps. In partnership with Map Kibera Trust, GT worked with Makueni, Baringo, and West Pokot counties to use OpenStreetMap to develop a base map for their counties and map the county’s projects. As part of the process, county officials from Budgeting, M&E, Lands and Planning, ICT, and other departments were trained to use Open Data Kit and the Kobo Toolbox to survey their territory. In order to carry out the process efficiently and increase citizen involvement and project feedback, youth from each ward were also trained. Together, they not only mapped the project locations and basic details by visiting each project, but also photographed them and took notes on their completion status, operational status, and apparent quality.

This feedback was compiled by GroundTruth on a demonstration website for each county. The maps were also developed into print versions which could be used during the PB meetings themselves, and used and shared by officials who are often more comfortable with printed maps.

The work has paid off, as some counties have now completed a second phase of the project, receiving additional training on how to execute the process themselves and how to work with the data. All the maps and data stored in OpenStreetMap is open; the feedback on the projects is visible through the linked website. The purpose of the maps is to help the counties and the public to be able to track projects and budget expenditure. In the new phase of work completed in December 2019, budgeted contract amounts are also included on the site.

By working closely with both youth and government Data Fellows, Map Kibera and GroundTruth are currently supporting the counties to continue to utilize the process and better integrate it with their finance, M&E and planning departments, and work with their new GIS officers. Meanwhile, other counties are looking to work with the same process. The future of devolved governance and citizen accountability through mapping looks bright.

Announcing Release of New Map Kibera Research: Open Mapping from the Ground Up

Posted: October 12th, 2017 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Accountability and Transparency, OSM, Research | Leave a comment »Earlier this year, I was fortunate to have the chance to research some of Map Kibera’s work over the past 8 years in the area of citizen accountability and transparency. I was interested especially in whether the maps made in Kibera had had an impact beyond the life of each project, since they were available online on OpenStreetMap and our own website, and distributed offline via paper maps and wall murals. I looked at three sectors we’d worked on —  education, water and sanitation, and security — and interviewed those who had commissioned, been given, or discovered the related maps in some way. I looked particularly at whether citizens had been able to use the maps to improve accountability and governance. This research has now been published as part of the Making All Voices Count Practitioner Research and Learning series.

The results were surprising. I found that maps had been used for a wide variety of purposes which we hadn’t known about before, including arguing for policy changes and reallocating donor resources in Kibera.

The research process involved first trying to track the maps, which was not easy. The Map Kibera team, working with research assistant Adele Manassero, asked around in Kibera, looked on social media, combed through blog posts, and otherwise tried to find out who used our maps and why. Working with open data can be messy this way. We found a number of people who said they had indeed been working with our data. Some were from various NGOs, others were in government. We also followed up on those we’d handed out the map to directly, like school heads and community leaders.

The schools map in particular, which had been the most widely distributed of our maps by far in paper form, had been used for many purposes. It had even been photocopied by the local education official to hand out to visitors. The local Member of Parliament had used it to reach out to the informal schools and create a WhatsApp group to communicate about key school information — Â and to petition Parliament for increased education resources for students in Kibera.

Part of the message here is that by sharing information widely, both digitally and on paper, AND with the backing and network of a trusted local team — Map Kibera — you can make room for impacts beyond a narrow project purpose usually associated with data collection. With all of the emphasis in ICT4D on designing directly for the end user, data collection is usually still done for the end user called the donor — or the organization’s HQ, or governmental higher-ups. Sometimes this data doesn’t even get used. In this case, I found that the better we targeted a variety of local potential “end usersâ€, like leaders of local associations, teachers, and CBOs, the more we saw uptake and impact even without intensive chaperoning of the information. Maps wound up being repurposed. This is the way, I believe, open data is supposed to work.

I suppose then the question is, why did it work this way, when so often it doesn’t? I found that collection and sharing of information by trusted local residents helped lend validity to the information, improve trust and communications between government and citizens, and bring informal sectors into the light in a way that benefitted the community. If anyone wanted to know where the data came from, the folks collecting it were right there, visible, identifiable and relatively unbiased. They could also be called upon to make corrections. Schools indeed have reached out, and recently a lot of updates were made to that data by the team. The analog method of change — being able to call someone, who lives in your neighborhood, and refer to a paper visual — is key to local social impact, even if the information collected is digital.

I’ll be blogging about a number of other things I found interesting out of this research in the weeks to come. Stay tuned!