Mapping Participatory Budgeting in Kenya’s Counties

Posted: March 13th, 2020 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Accountability and Transparency, citizen feedback, Citizen Generated Data, Governance, kenya, openstreetmap, OSM, World Bank | Tags: Citizen Generated Data, Counties, Open Data, Participatory Budgeting | Leave a comment »

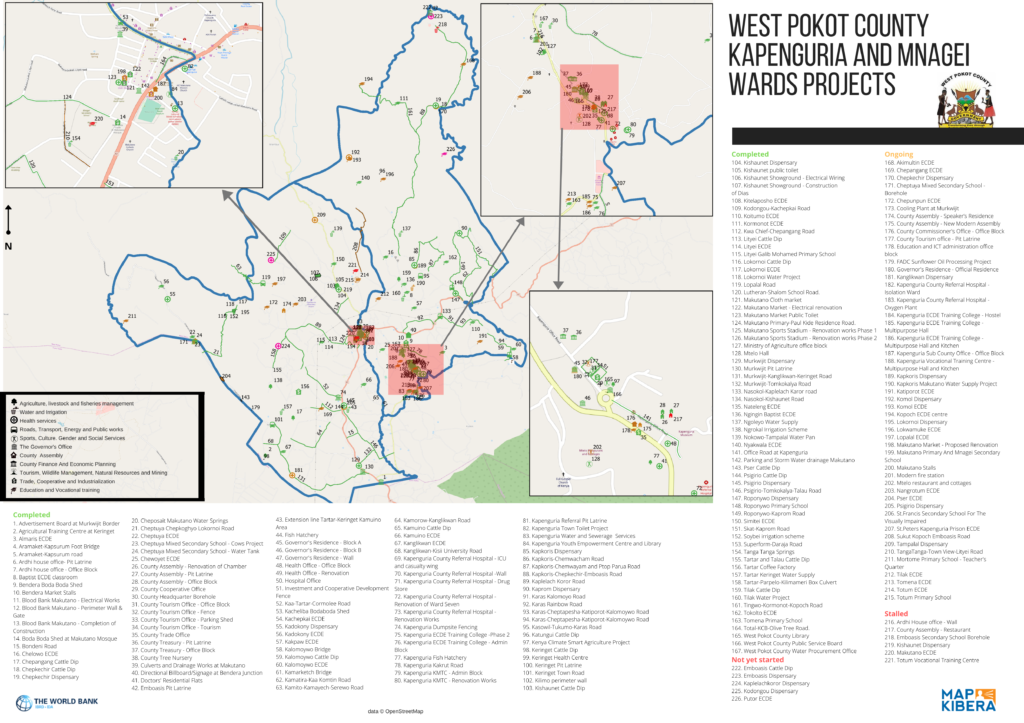

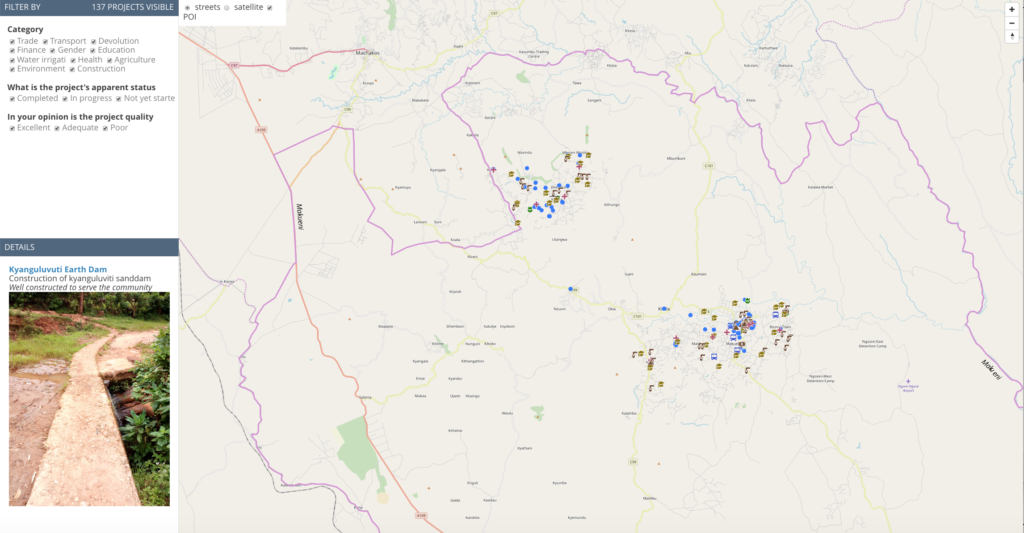

GroundTruth Initiative has been working for the past two years with three county governments in Kenya, along with partners the World Bank and Map Kibera Trust, to map and gather detailed feedback on county-funded projects. By training both county officials and local youth, while working cross-departmentally on data resources, GroundTruth has helped refine a process for citizen engagement which both increases transparency and accountability and provides much needed data and digital maps for the county.

In 2010, Kenya created a new constitution which focused on devolution of power to 47 new counties. Rather than focus development planning and budgets entirely at the national level, or in sub-regions which encompassed vastly different terrain and needs, the new constitution gave power to local officials and governors in the counties. Along with that came a need for new systems for finance and data. Starting up new processes and linking them to national systems was best done through digital means, but not all counties were ready technologically for these requirements.

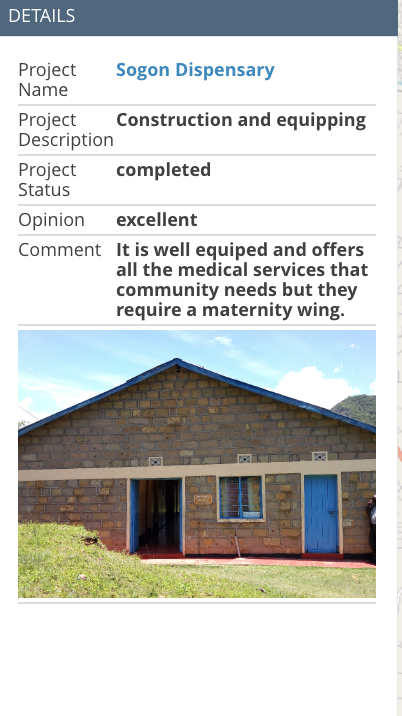

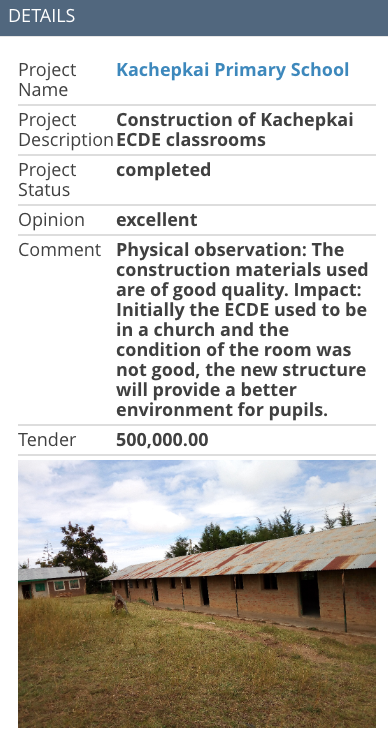

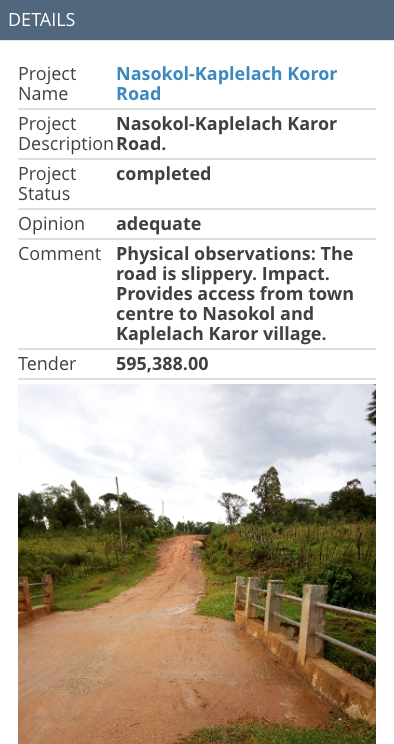

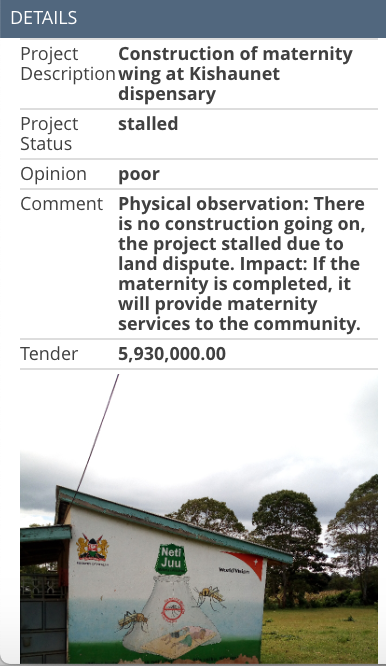

In 2015, the World Bank began to support select counties to engage their citizens in a process of participatory budgeting. Citizens gathered in each subsection of the county, down to the village level, and prioritized the greatest needs. Budgeted projects included everything from new hospital wings to small dams and footbridges to new water points and classrooms. The process repeated each year, but it was difficult to track progress on the projects and to know where they were located so as to best allocate resources the following year. There were very few up to date digital or print maps showing county projects or pre-existing social resources and features.

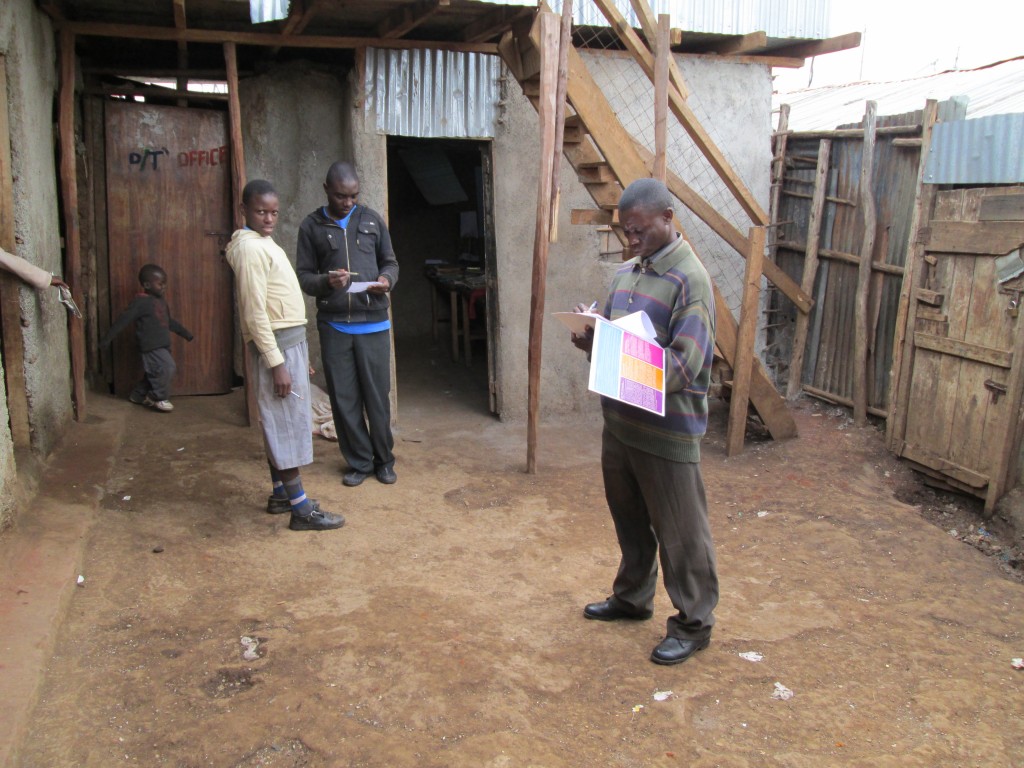

GroundTruth Initiative started working with counties in 2017 to help them create such maps. In partnership with Map Kibera Trust, GT worked with Makueni, Baringo, and West Pokot counties to use OpenStreetMap to develop a base map for their counties and map the county’s projects. As part of the process, county officials from Budgeting, M&E, Lands and Planning, ICT, and other departments were trained to use Open Data Kit and the Kobo Toolbox to survey their territory. In order to carry out the process efficiently and increase citizen involvement and project feedback, youth from each ward were also trained. Together, they not only mapped the project locations and basic details by visiting each project, but also photographed them and took notes on their completion status, operational status, and apparent quality.

This feedback was compiled by GroundTruth on a demonstration website for each county. The maps were also developed into print versions which could be used during the PB meetings themselves, and used and shared by officials who are often more comfortable with printed maps.

The work has paid off, as some counties have now completed a second phase of the project, receiving additional training on how to execute the process themselves and how to work with the data. All the maps and data stored in OpenStreetMap is open; the feedback on the projects is visible through the linked website. The purpose of the maps is to help the counties and the public to be able to track projects and budget expenditure. In the new phase of work completed in December 2019, budgeted contract amounts are also included on the site.

By working closely with both youth and government Data Fellows, Map Kibera and GroundTruth are currently supporting the counties to continue to utilize the process and better integrate it with their finance, M&E and planning departments, and work with their new GIS officers. Meanwhile, other counties are looking to work with the same process. The future of devolved governance and citizen accountability through mapping looks bright.

New Report Published on Sustainability in OpenStreetMap for Development

Posted: March 10th, 2020 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Governance, openstreetmap, OSM, Research, Sustainability, World Bank | Tags: openstreetmap, sustainability | Leave a comment »

A new report, written by GroundTruth director Erica Hagen for the World Bank’s GFDRR (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery), examines sustainability challenges and strategies for the use of OpenStreetMap in developing countries.

Over the past several years, OpenStreetMap (OSM) has been used by an increasing number of aid and development organizations, like the World Bank’s Open Cities initiative, with the aim of supporting a wide variety of development and humanitarian objectives. OSM mapping has taken place in response to natural disasters (like the Haitian and Nepalese earthquakes), in order to empower slum communities (such as Kibera, in Nairobi), to help mitigate or prevent disease outbreaks (Ebola, and Malaria), or simply to promote the use of open map data among government officials and others already using GIS (for example in Kinshasa, DRC).

However, mapping efforts have frequently run into challenges as mappers and data users try to navigate issues of open data and technology to keep data and maps current and impactful. It can be difficult to keep trained volunteer mappers engaged, build and fund mapping organizations, engage governments productively, develop local management capacity, create successful mapping businesses around OSM, to name just a few.

This research explores the many facets of OSM in development and its “sustainabilityâ€. It examines the definition of sustainability, reviews existing literature about sustainability in ICT4D, and identifies four dimensions of “sustained benefit†which can help us to understand factors that will influence longer-term success. The paper identifies seven different kinds of actors which typically work with OSM in developing economies, and their particular challenges, illustrated by several case study examples.

The report then suggests a way forward for funders, practitioners, and others to move toward greater benefits for all given the constraints of OSM globally, the ethical considerations of digital open mapping, and the challenges of open source and open data projects generally as technology matures.

Sustainability in OpenStreetMap: Building a more stable ecosystem in OSM for Development and Humanitarianism

A white paper prepared for the Open Data for Resilience Initiative, GFDRR Labs, World Bank.

Looking Back with Making All Voices Count

Posted: May 23rd, 2017 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: kenya, openstreetmap, Research | Tags: Evaluation, Impact, MAVC | Leave a comment »I’ve recently had the opportunity to spend some time learning and thinking about Map Kibera’s work, thanks to a practitioner research grant from Making All Voices Count.

Those who work in the NGO and nonprofit sphere like me might not be surprised to learn that we’ve had precious little opportunity to do evaluation on our work over the past 8 years. So, I welcomed this chance to look into some of the impacts and possibly unintended directions that our work has taken during this time.

While I’ve written about Map Kibera a number of times from the reflective standpoint, I hadn’t had the chance to try to track down some of the specific results. Especially when it comes to who’s using our maps and data, and for what. We have a strong commitment to open data, meaning that you can easily access our information and maps either directly through our website, or through OSM itself. That means it’s hard for us to know who has used them (and if you have, but haven’t been in touch with us to let us about it, please help me out by emailing me!).

I haven’t yet fully analyzed everything I’ve gathered through a series of interviews, focus group discussions, and by reviewing our social media and visitors logs over the years, but a few things have stood out so far. Here is just a sampling:

-

There were a number of cases we were able to track down of data being used without our knowing about it. For open data, that’s a success, right? It means that there have been changes in actual programming for Kibera, especially in targeting interventions to specific geographical areas, finding local partners, and directing donor resources. Information by itself may not produce systemic changes, but could redirect resources in an uncoordinated way to places that most need it. In other words, it can make aid more effective. With some coordination this might be a stronger effect.

-

With some support by intermediaries such as Map Kibera, information like maps can help produce larger systemic shifts. But the level of support required is a question – given that this isn’t typically well resourced. We had some impacts particularly within the education system which were large considering the amount of funding we had, but we couldn’t sustain intensive support. A larger question about the appropriate role of such an intermediary came up again and again.

-

Trust among stakeholders is one major outcome, which has little to do with technology and a lot to do with relationship building. In this sense, information and maps are a kind of tool for getting on the same page, perhaps, or removing some of the bias on either side. There is a lot of mistrust in informal settlements (between citizens and government, citizens and NGOs or CBOs, schools and education officials, etc). This needs to be overcome for improvements in key sectors like education and water/sanitation, two areas I looked into.

-

The value of “being recognized†or being made visible was something that came up repeatedly. A perceived legitimization through transparency. I think there are two things here: being able to speak out or have “voice†in the sense of self-representation; and becoming legible – that is, transparent – which may have more to do with knowing the facts than giving voice to opinions and perspectives.

-

Keeping data up-to-date is a huge challenge. And it can hinder scaling up and expansion because of the effort required.

-

Technology is still a challenge, in that most people don’t use the internet OR may have smartphones but still don’t use them to their full capacity. Offline outreach and printed materials are key, still.

-

Those taking part in our projects over the years have seen a lot of personal benefit, and some of this has been unexpected (on my part). For instance, the value of contests and credentials – winning an online contest for a news story, even an obscure one without any prize, was a huge highlight, as was gaining press credentials or even a simple ID badge to be identified as a member of the organization.

Clearly there is a lot to unpack in each of the points above, and there are many more topics to explore as well! If this is of interest to you, stay tuned for the publication.

Making Education Information Available to All in Kibera

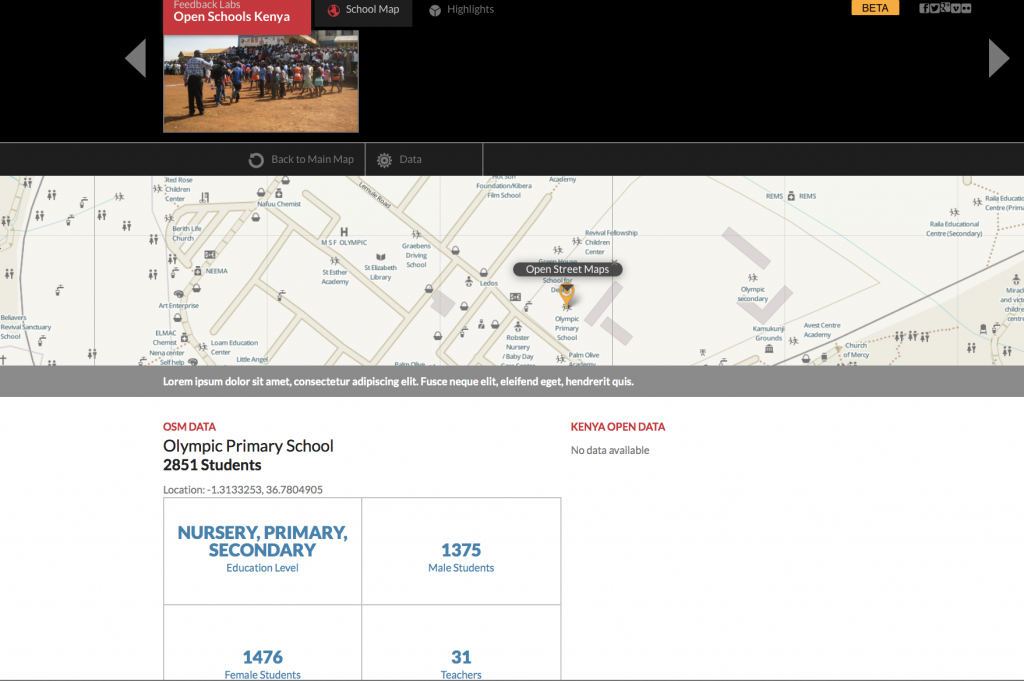

Posted: July 9th, 2014 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, kenya, openstreetmap | Tags: education, Feedback Labs, Gates Foundation | 1 Comment »How can all the information about Kenyan schools, including data released by the Kenyan government, and citizen mapping, have a greater impact on education? We’ve been working for the past few months on a project to make information about schools much more available and useful in Kenya. It’s a joint operation between GroundTruth Initiative, Map Kibera, Development Gateway, Feedback Labs, and the Gates Foundation among others.

Many people collect information about education – and they sometimes make it open and free to use. So, why isn’t it easy to find information about a particular school – for a parent, or for an education researcher? Much of the information that’s out there isn’t connected to the other data – and especially when it comes to informal schools, which provide a great deal of the education services in places like informal settlements.

Citizen data – like mapping schools using OpenStreetMap – should also be easy to combine and compare with official education data. And finally, all this info could be accessible and useful to everyone from parents to policymakers.

So, we’ve started with Kibera as a test location for the Open Schools Kenya project.

Over the past few months, the Map Kibera team has engaged parents, school leaders, and education officials in Kibera to find out how the informal school sector can be more visible, and to assess the demand for information on education. Now, a widespread effort is underway by Map Kibera to make sure that the schools data that the team collected a few years ago is still accurate, and to add new info as well. We’re also collecting photos of each school, no matter how small. Every one will have a page on the website, really bringing the informal school sector to light. Formal schools in Kibera will be there too.

Much of the work so far has been around engaging important leaders in the community, who care about local kids getting the best education. Mikel Maron of GroundTruth was recently in Nairobi working on the project and will be updating in a separate post about this busy trip. Ultimately, the community wants to know more about its schools, and to improve them. So do education supporters throughout Kenya.

But beyond this important mission of organizing and making interoperable many data sets across the vast education sector in Kenya, we’re also working on an ambitious hypothesis: that parents and community leaders in education will want to provide feedback on schools, which in turn will inform policy and improve individual schools. Ultimately, our platform will be a place where people can not only be consumers of information, but will provide their own opinions and suggestions on schools, and, importantly, submit corrections and updates to the data on the site. Given the early positive response to these ideas, we’re optimistic that this will be possible in Kibera and also Kenya-wide.

The project is not just about education, either. It has far-reaching potential in other sectors as well. We hope to demonstrate that citizen data, official data, academic research and more can come together and be part of a conversation with those on the ground who feel the impact most of government policy in every sector – ordinary citizens. And, that this kind of conversation means that people “own†their own information, and we can see the beginnings of a true “feedback loop†or dialogue between citizens and government, through the medium of shared data.

This article was originally posted on the Map Kibera blog, July 3, 2014.

Challenges of OpenStreetMap in Institutions

Posted: March 4th, 2014 | Author: mikel | Filed under: openstreetmap | Leave a comment »This Thursday, the World Bank will hold an event on how large organizations can better engage with projects that involve OpenStreetMap. That’s my take anyway! I’ll be part of a panel with good folks like Nithya Raman from Transparent Chennai and Rob Baker from, um, everything. I’m hoping this is a good chance to get some strong ideas percolating through the bureaucratic membranes. My slides are here. You should come and maximize with us! (storify stream of the event here)

Ahead of the event, I’m reflecting (rambling?) on what’s been challenging for me to bring OpenStreetMap, citizen journalism, and participatory technologies into the institutional context of large development organizations. This interests me because bringing together “community” and “authoritative” data and approaches will produce better results. I’m coming from the assumption that the methodologies of these tools in community development are pretty sound on their own, and we have good ways to continually improve what we do. The struggle I want to examine is the associated organizational change in large institutions. That’s where the gap in impact lies, not in anything fundamental in the methodologies.

The event came to be after I successfully bugged Stephen Davenport (who’s now at the World Bank) to publish a somewhat forgotten, but proven very useful, Draft HowTo Note on Community Mapping. I regularly included this document in a package to introduce our work to others (as well as the Case Study on Map Kibera and LearnOSM). And I soon learned the HowTo would be an independently published chapter. (It’s published, read it.) And we’d hold an event with smart and influential people (that means you).

Scaling Up? From http://www.flickr.com/photos/wlscience/3071678864/

So we are “maximizing” at the event. Or, let’s make it bigger. I’ve often been asked about scaling up community mapping. Like, it’s great that you mapped one neighborhood, now let’s do the entire city, the entire district, the country, 12 countries. It doesn’t work like that. Communities can’t be “industrialized”, but always take intensive engagement. That doesn’t mean that things can’t “grow” … they can very fast as evidenced by the OpenStreetMap community as a whole. But that networked growth occurs by building relationships at all scales, not simply multiplication. Still, if you want to map the 100 largest slums in the world, I do have a plan, it just won’t be a cookie cutter model.

There’s a big mismatch in time scale. Organizations work on project timelines and annual budget timelines. Notice the substantial increase in projects initiated late in the fiscal year. Projects end when they end. Communities don’t end. A thriving community of mappers takes way more time to develop than a project timeline, and especially with a real physical community, there are relationships and expectations that extend beyond the institutional structure. I don’t have a good answer for this, and I expect to see this completed solved on Thursday ;).

World Bank projects approved by month. Is it just because it’s better to start projects in June? From http://www.chezvoila.com/blog/datadive2

Publications also must deal with time scale mismatch. The original research for the Interactive Community Mapping chapter started about 3 years ago. And the research was excellent, but the conclusions were drawn at that point in the past. Choose another arbitrary point in time, and you get another conclusion. In Kibera, the gap between “need for information” and “government engagement” has closed substantially, and there’s a different story in the balance of “results” and “process oriented” methodologies. Map Kibera Trust has successfully undertaken both modes repeatedly, in many places, engaging community and delivering specific results for a number of partners, including government, most excellently in the 2013 election work. This years-long timeline was actually by design! While there wasn’t a solid results-driver to start, the whole approach was pretty new at that point, and the political climate in Kenya very different. Learning was desired and required, and this needed to play out over the years to be effective.

On the other hand, Ramani Tandale has had a lot of promise and interest, but hasn’t reached that potential yet. Specifically, the original “need for information” was driven by the urban sector of the World Bank, to integrate this work into slum upgrading programs (which were excellent actually). But then the Tech Team Lead in that Tanzania office left, and a number of other schemes didn’t materialize. In other words, the convening role of the World Bank did not have real long term consequence for the community. At least not yet. Despite that, we’ve worked to continue the Tandale project and the people of Tandale have shown incredible interest, such as paying for internet out of their own savings group funds! But they have not received the organizational support, despite the starring role Tandale takes in many World Bank presentations, nor yet the continued solid connection to government to respond to needs. Organizational support and this final connection may be the most difficult piece of the puzzle.

Incentives are super complicated. All of us need to survive, many of us want to contribute something more. It’s a hard balance, and harder still for someone strugggling economically. Ground Truth has had so many different structures in this way. In Tandale, the university students did actually get a stipend for the “industrial training module”, which was paid out of project funds. That’s standard arrangement apparently. True, it didn’t have much correlation with long term interest … the 2 or 3 strongest folks have stuck with it out of their enthusiasm (though they’ve benefited financially too from their continued engagement). That’s natural. It is worth considering that financial incentive operates at all levels; even government officials in many places expect to receive a “per diem” for taking part in a training, or travelling to a conference (especially from the World Bank!). I don’t think you can simply equate presence or absence of financial reward with motivational success.

But clearly there are other benefits. One of the key benefits, and key distinctions of “Interactive Community Mapping” from participatory mapping of the past, is the connection to a global technical commons like OpenStreetMap. Just like OSM has fundamentally changed GIS into a global network, the same goes for participatory GIS. What this means is that data contributed for one purpose, like community engagement, still exists for special purpose mapping, and vice versa. The commons has its own sustainability, and allows for unintended use … the honest reckoning that we don’t know all the potential applications for these maps, but the option is there. It connects community members directly to a global network of mappers, who can share not only data, but share a data community. What “ICM” and “PGIS” do have in common is an acknowledgement that some places are not even accessible to professionals, or that professionals would do a comparatively worse job then people who know a place.

Mappers in Nepal, Mapping for the Philippines. From http://kathmandulivinglabs.org/blog/crisis-in-the-philippineswe-are-with-you/

With a global network structure, new organizational roles are emerging. Some call these infomediaries. There are “local organizations” whose specific mission is to support use of ICT practices in civil society and communities … they work between global technical networks and the needs of local communities. That is what Map Kibera Trust has become. It’s a gap in Tanzania so far. For HOT in Indonesia, there is for all real purposes a “HOT Indonesia” organization, which runs itself and serves this purpose. The groups taking part in GFDRR’s OpenCities fit this role. Many of the groups GroundTruth has worked with (as international ICM “experts”) fit this mold, such as Grassroots Jerusalem and Transparent Chennai. Kenya has a number of these kinds of groups, including Open Data Institute, Mzalendo, Map Kibera, to some extent Ushahidi/iHub, etc.

Some other quick final thoughts, but I think potent ideas for large organizations looking to do community mapping.

With a global network structure, people in large organizations can be directly involved in communities. OpenStreetMap is meant to be easy for anyone to contribute to, and gets easier all the time. Yet, it’s a rare person developing the space for a project inside large organizations that learns to map before designing a project. It’s takes about 30 minutes, and it will make everything a lot more real and easier to talk about.

While we’re at it, can we just stop hedging with “Interactive Community Mapping”, and just talk about OpenStreetMap?! Aside from balloon and kite mapping, which is a different awesome technology, no one is using Google Map Maker seriously for this kind of work. Let’s get on with it and acknowledge, OpenStreetMap is winning, the world needs OpenStreetMap.

And last, asking a favor. Update contracts to reflect open source and open data. The projects I work on are specifically about production for the commons. Yet most contracts still hold intellectual property rights of the work of the contract. This requires further discussion and annexes to standard contracts, every time. I’m sure we can solve this just once.

See you on Thursday!