Mapping Participatory Budgeting in Kenya’s Counties

Posted: March 13th, 2020 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Accountability and Transparency, citizen feedback, Citizen Generated Data, Governance, kenya, openstreetmap, OSM, World Bank | Tags: Citizen Generated Data, Counties, Open Data, Participatory Budgeting | Leave a comment »

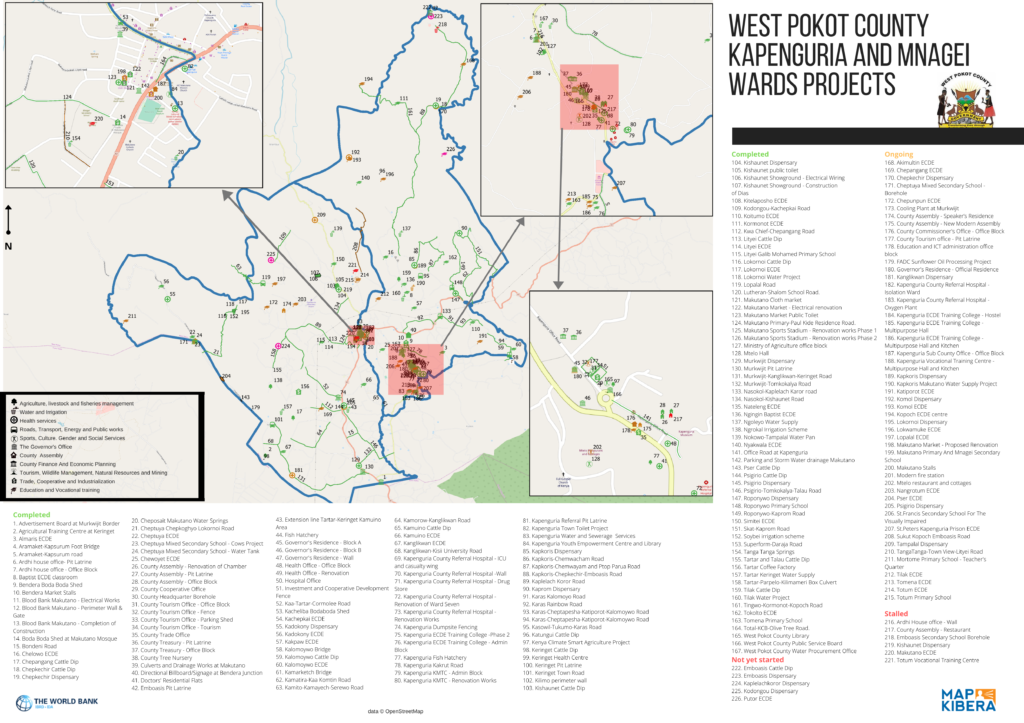

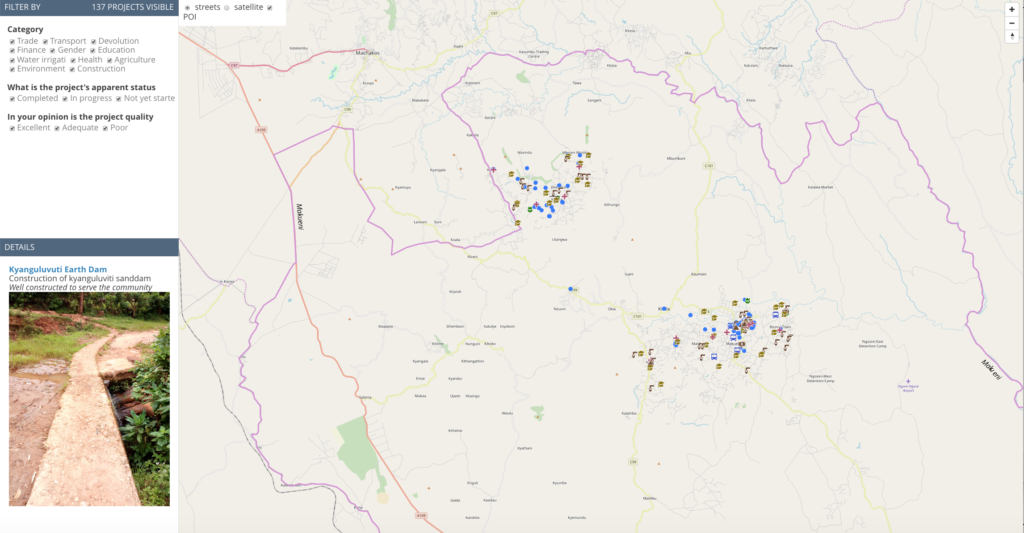

GroundTruth Initiative has been working for the past two years with three county governments in Kenya, along with partners the World Bank and Map Kibera Trust, to map and gather detailed feedback on county-funded projects. By training both county officials and local youth, while working cross-departmentally on data resources, GroundTruth has helped refine a process for citizen engagement which both increases transparency and accountability and provides much needed data and digital maps for the county.

In 2010, Kenya created a new constitution which focused on devolution of power to 47 new counties. Rather than focus development planning and budgets entirely at the national level, or in sub-regions which encompassed vastly different terrain and needs, the new constitution gave power to local officials and governors in the counties. Along with that came a need for new systems for finance and data. Starting up new processes and linking them to national systems was best done through digital means, but not all counties were ready technologically for these requirements.

In 2015, the World Bank began to support select counties to engage their citizens in a process of participatory budgeting. Citizens gathered in each subsection of the county, down to the village level, and prioritized the greatest needs. Budgeted projects included everything from new hospital wings to small dams and footbridges to new water points and classrooms. The process repeated each year, but it was difficult to track progress on the projects and to know where they were located so as to best allocate resources the following year. There were very few up to date digital or print maps showing county projects or pre-existing social resources and features.

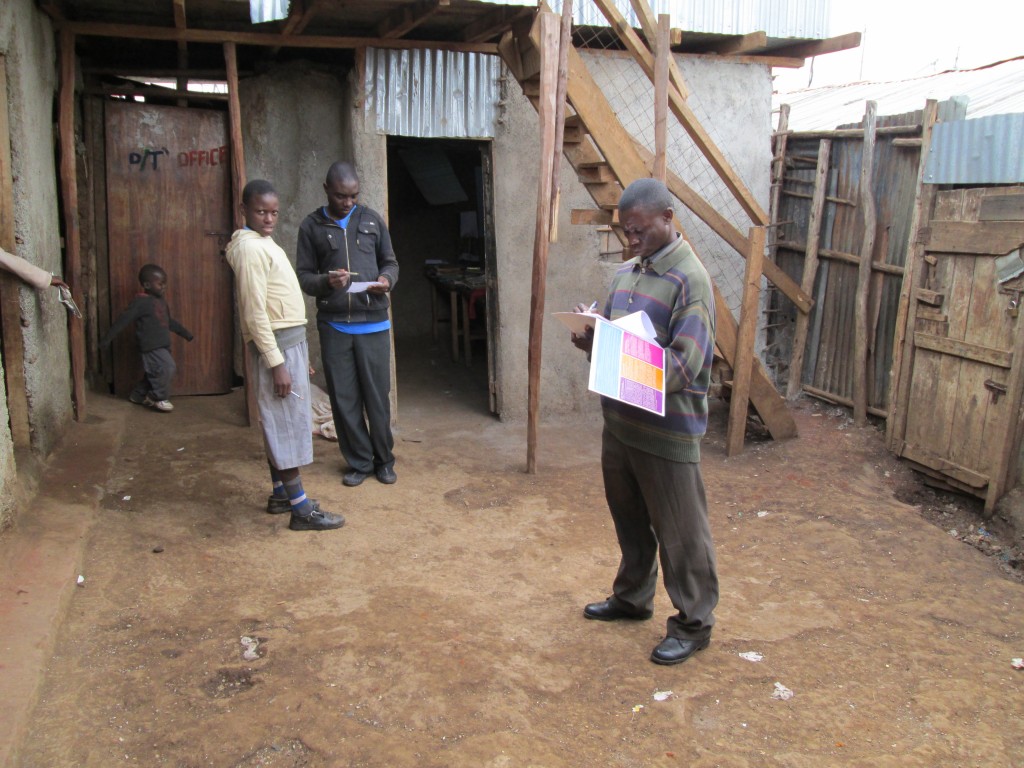

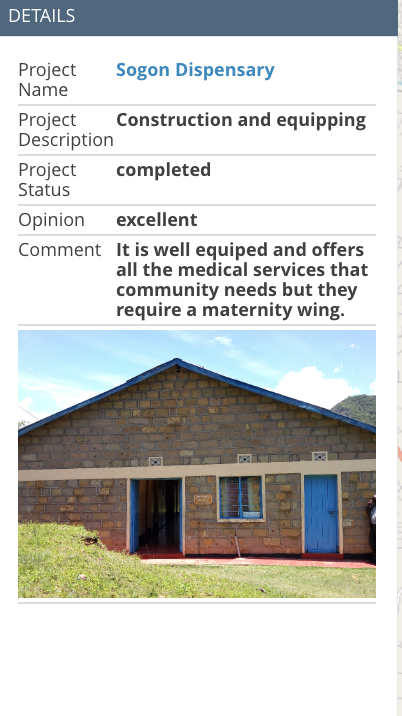

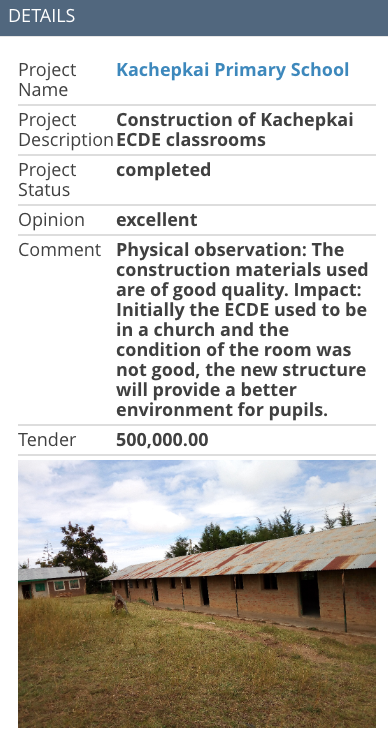

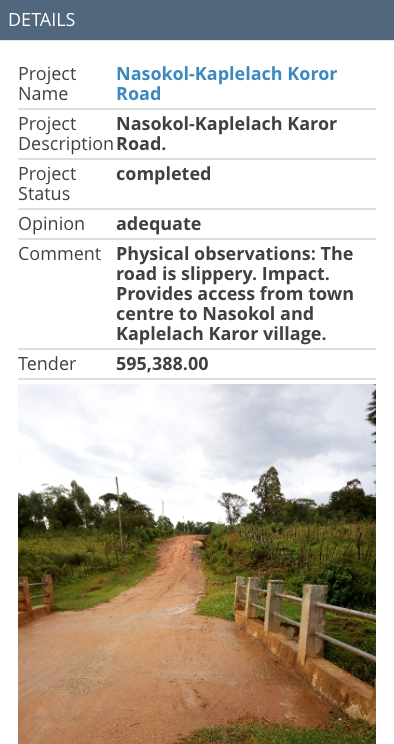

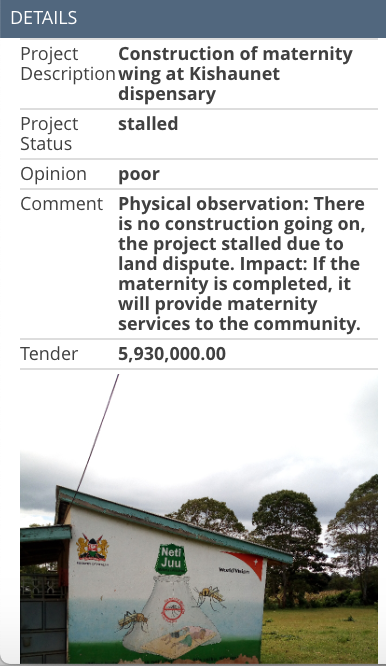

GroundTruth Initiative started working with counties in 2017 to help them create such maps. In partnership with Map Kibera Trust, GT worked with Makueni, Baringo, and West Pokot counties to use OpenStreetMap to develop a base map for their counties and map the county’s projects. As part of the process, county officials from Budgeting, M&E, Lands and Planning, ICT, and other departments were trained to use Open Data Kit and the Kobo Toolbox to survey their territory. In order to carry out the process efficiently and increase citizen involvement and project feedback, youth from each ward were also trained. Together, they not only mapped the project locations and basic details by visiting each project, but also photographed them and took notes on their completion status, operational status, and apparent quality.

This feedback was compiled by GroundTruth on a demonstration website for each county. The maps were also developed into print versions which could be used during the PB meetings themselves, and used and shared by officials who are often more comfortable with printed maps.

The work has paid off, as some counties have now completed a second phase of the project, receiving additional training on how to execute the process themselves and how to work with the data. All the maps and data stored in OpenStreetMap is open; the feedback on the projects is visible through the linked website. The purpose of the maps is to help the counties and the public to be able to track projects and budget expenditure. In the new phase of work completed in December 2019, budgeted contract amounts are also included on the site.

By working closely with both youth and government Data Fellows, Map Kibera and GroundTruth are currently supporting the counties to continue to utilize the process and better integrate it with their finance, M&E and planning departments, and work with their new GIS officers. Meanwhile, other counties are looking to work with the same process. The future of devolved governance and citizen accountability through mapping looks bright.

Looking Back with Making All Voices Count

Posted: May 23rd, 2017 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: kenya, openstreetmap, Research | Tags: Evaluation, Impact, MAVC | Leave a comment »I’ve recently had the opportunity to spend some time learning and thinking about Map Kibera’s work, thanks to a practitioner research grant from Making All Voices Count.

Those who work in the NGO and nonprofit sphere like me might not be surprised to learn that we’ve had precious little opportunity to do evaluation on our work over the past 8 years. So, I welcomed this chance to look into some of the impacts and possibly unintended directions that our work has taken during this time.

While I’ve written about Map Kibera a number of times from the reflective standpoint, I hadn’t had the chance to try to track down some of the specific results. Especially when it comes to who’s using our maps and data, and for what. We have a strong commitment to open data, meaning that you can easily access our information and maps either directly through our website, or through OSM itself. That means it’s hard for us to know who has used them (and if you have, but haven’t been in touch with us to let us about it, please help me out by emailing me!).

I haven’t yet fully analyzed everything I’ve gathered through a series of interviews, focus group discussions, and by reviewing our social media and visitors logs over the years, but a few things have stood out so far. Here is just a sampling:

-

There were a number of cases we were able to track down of data being used without our knowing about it. For open data, that’s a success, right? It means that there have been changes in actual programming for Kibera, especially in targeting interventions to specific geographical areas, finding local partners, and directing donor resources. Information by itself may not produce systemic changes, but could redirect resources in an uncoordinated way to places that most need it. In other words, it can make aid more effective. With some coordination this might be a stronger effect.

-

With some support by intermediaries such as Map Kibera, information like maps can help produce larger systemic shifts. But the level of support required is a question – given that this isn’t typically well resourced. We had some impacts particularly within the education system which were large considering the amount of funding we had, but we couldn’t sustain intensive support. A larger question about the appropriate role of such an intermediary came up again and again.

-

Trust among stakeholders is one major outcome, which has little to do with technology and a lot to do with relationship building. In this sense, information and maps are a kind of tool for getting on the same page, perhaps, or removing some of the bias on either side. There is a lot of mistrust in informal settlements (between citizens and government, citizens and NGOs or CBOs, schools and education officials, etc). This needs to be overcome for improvements in key sectors like education and water/sanitation, two areas I looked into.

-

The value of “being recognized†or being made visible was something that came up repeatedly. A perceived legitimization through transparency. I think there are two things here: being able to speak out or have “voice†in the sense of self-representation; and becoming legible – that is, transparent – which may have more to do with knowing the facts than giving voice to opinions and perspectives.

-

Keeping data up-to-date is a huge challenge. And it can hinder scaling up and expansion because of the effort required.

-

Technology is still a challenge, in that most people don’t use the internet OR may have smartphones but still don’t use them to their full capacity. Offline outreach and printed materials are key, still.

-

Those taking part in our projects over the years have seen a lot of personal benefit, and some of this has been unexpected (on my part). For instance, the value of contests and credentials – winning an online contest for a news story, even an obscure one without any prize, was a huge highlight, as was gaining press credentials or even a simple ID badge to be identified as a member of the organization.

Clearly there is a lot to unpack in each of the points above, and there are many more topics to explore as well! If this is of interest to you, stay tuned for the publication.

Making Education Information Available to All in Kibera

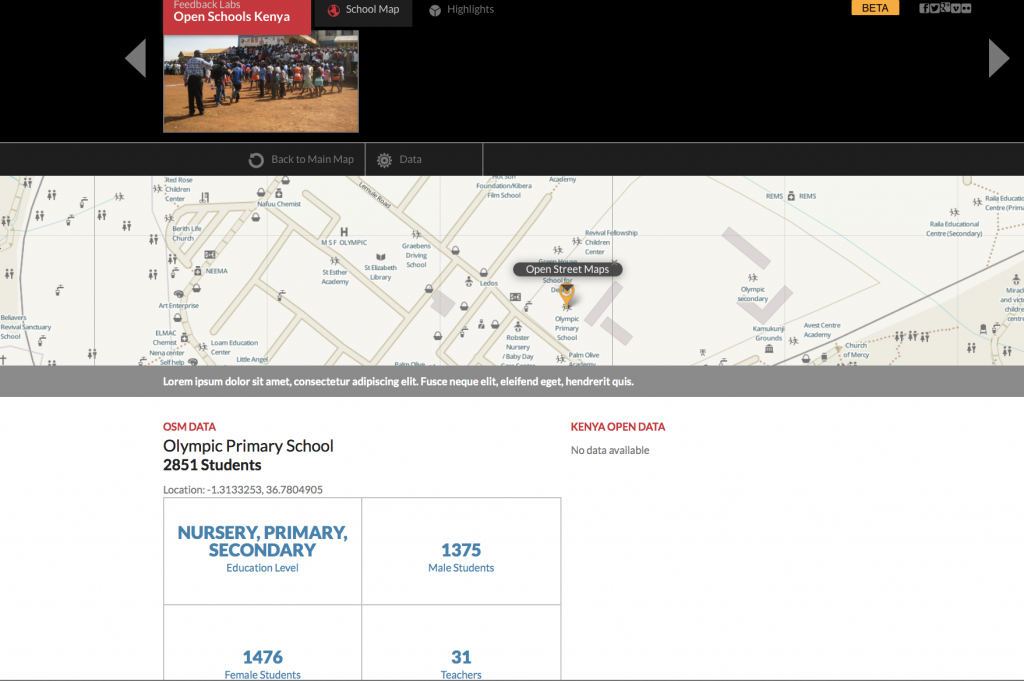

Posted: July 9th, 2014 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, kenya, openstreetmap | Tags: education, Feedback Labs, Gates Foundation | 1 Comment »How can all the information about Kenyan schools, including data released by the Kenyan government, and citizen mapping, have a greater impact on education? We’ve been working for the past few months on a project to make information about schools much more available and useful in Kenya. It’s a joint operation between GroundTruth Initiative, Map Kibera, Development Gateway, Feedback Labs, and the Gates Foundation among others.

Many people collect information about education – and they sometimes make it open and free to use. So, why isn’t it easy to find information about a particular school – for a parent, or for an education researcher? Much of the information that’s out there isn’t connected to the other data – and especially when it comes to informal schools, which provide a great deal of the education services in places like informal settlements.

Citizen data – like mapping schools using OpenStreetMap – should also be easy to combine and compare with official education data. And finally, all this info could be accessible and useful to everyone from parents to policymakers.

So, we’ve started with Kibera as a test location for the Open Schools Kenya project.

Over the past few months, the Map Kibera team has engaged parents, school leaders, and education officials in Kibera to find out how the informal school sector can be more visible, and to assess the demand for information on education. Now, a widespread effort is underway by Map Kibera to make sure that the schools data that the team collected a few years ago is still accurate, and to add new info as well. We’re also collecting photos of each school, no matter how small. Every one will have a page on the website, really bringing the informal school sector to light. Formal schools in Kibera will be there too.

Much of the work so far has been around engaging important leaders in the community, who care about local kids getting the best education. Mikel Maron of GroundTruth was recently in Nairobi working on the project and will be updating in a separate post about this busy trip. Ultimately, the community wants to know more about its schools, and to improve them. So do education supporters throughout Kenya.

But beyond this important mission of organizing and making interoperable many data sets across the vast education sector in Kenya, we’re also working on an ambitious hypothesis: that parents and community leaders in education will want to provide feedback on schools, which in turn will inform policy and improve individual schools. Ultimately, our platform will be a place where people can not only be consumers of information, but will provide their own opinions and suggestions on schools, and, importantly, submit corrections and updates to the data on the site. Given the early positive response to these ideas, we’re optimistic that this will be possible in Kibera and also Kenya-wide.

The project is not just about education, either. It has far-reaching potential in other sectors as well. We hope to demonstrate that citizen data, official data, academic research and more can come together and be part of a conversation with those on the ground who feel the impact most of government policy in every sector – ordinary citizens. And, that this kind of conversation means that people “own†their own information, and we can see the beginnings of a true “feedback loop†or dialogue between citizens and government, through the medium of shared data.

This article was originally posted on the Map Kibera blog, July 3, 2014.

Citizen election reporting in Kenya: A breakthrough in online-offline collaboration

Posted: May 2nd, 2013 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, kenya | Tags: elections, kenya, reporting | Leave a comment »The Kenyan elections were more than a month ago, but a debate continues in the crisis mapping community about whether the various technologies deployed to track and respond to outbreaks of violence were a confused and possibly dangerous mess, or a successful contribution to what was ultimately a peaceful (if disputed) process.

DO WE REALLY NEED ALL OF THOSE PROJECTS??? Do we really need 3 maps, 7 phone numbers, and several web-forms? Is that really such a crazy bad idea to have one coordinated number/web-form that could then have in the back-end multiple responders and organizations working together? – Anahi Ayala  (ICT Works blog post)

The criticism goes on to describe this duplication as irresponsible and dangerous, especially supposing that the submitted information has no real response mechanism.

While it’s true that having multiple public numbers for submitting information about one election is not ideal, I believe that behind the scenes was a much more encouraging process that has only just begun. Here’s why I think that in the balance, technology was part of the solution, not the problem, during Kenya’s elections:

1) Unprecedented collaboration among technologists, at least at a pilot level.

Map Kibera took part in elections monitoring by mapping and reporting through SMS, blogs and video throughout the election period on our multimedia sites, Voice of Kibera and Voice of Mathare in two slums. Kepha Ngito, our executive director, offers this extensive writeup of how the process looked behind the scenes, definitely worth a read. Map Kibera already had been working with Ushahidi-based websites and video news for three years in Kibera, and with blogging and video in Mathare for about two years; therefore neither project was created specifically for the election. Given our status as an established community-based group focusing on reporting and local information, we were ready to take on this event without creating any new technology.

As elections neared, more organizations began to set up temporary programming around election reporting. In particular, our team joined events held by Ushahidi around their Uchaguzi platform, and we began to think about how to collaborate: they as a national scope project and ourselves in-depth in two key communities. Ultimately, some members of our team worked throughout the election at the iHub headquarters of Ushahidi to monitor their reports coming in from Kibera and Mathare, and share our more detailed and verified reports with their system. This meant both reports and response could be tightly coordinated.

Would it have made sense to have used only one reporting number, that of Uchaguzi for instance? No, because Uchaguzi is no longer active, while Map Kibera is building up a long term citizen engagement including this SMS number. It made more sense to work on interoperability and coordination.

2) Unprecedented coordination among community-based groups

What was the key to all the information coming in, and the verification process?

At the community level, there was unprecedented coordination among a variety of agencies who normally do not work together. Concerned groups put aside whatever challenges normally keep them operating separately, and pledged support to each other in order to serve the good of the community. This kind of network is a real breakthrough in coordination locally given the challenges that often prevent such teamwork, and it naturally came from desire for security in the slum not any outside impetus. As Kepha writes:

KCODA, Pamoja FM, Map Kibera, Kamukunji Pressure Group, CREAW, the Langata District Peace Committee, Community Policing groups and the office of the District Commissioner joined efforts to create a network called the Kibera Civic Watch Consortium, a body that would respond to and coordinate the community’s efforts to maintain peace and provide interventions where possible. (Kepha Ngito, How slum communities came together to help prevent election violence)

3) Response and verification

It was this background offline coordination that would allow for immediate election-day verification and constant liaising with security groups, both official and community led, in case of any problem. The online-offline coordination often involved both SMS into the system, and phone calls to security or other key people to keep tensions down.

…We stationed our trained citizen reporters in each polling station to be relaying SMS news to our verification team to be verified and approved before being posted on our Voice of Kibera and Voice of Mathare websites.The Map Kibera verification team dealt with every information that came in, calling back and forth to establish the facts and figures about every report sent in. Our video teams rushed to scenes, most of which were not known or easily accessed by the mainstream or foreign press to capture instant news which they edited and uploaded on Youtube. Members also took photos and posted them to our blogs and Facebook group. In this verification process, the team succeeded in dismissing several false alarms, wrong information and propaganda for violence. In addition and in response, security organs and emergency service providers enhanced their presence in these areas highly reducing chances of violence. In one instance, when many reports were sent about youth gathering around in groups in one area of Kibera, after several phone calls with the security organs, the Police Commissioner authorized a chopper to fly around conducting a security check, the crowds soon dispersed and calm returned. (Kepha Ngito, How slum communities came together to help prevent election violence)

I heard a number of claims floating around about technology platforms being directly responsible for police or security response. I would advise that these be investigated closely. In the case of both Kibera and Mathare, if anything it was this type of “online†or SMS-based reporting in conjunction with offline personal and official networks, connected often through ordinary phone calls, which activated response, not a pure technical system.

Bringing together the various kinds of technical reporting options with great local networks can create response processes that are effective, but not overly sensitive to false alarm reports.

4) Good citizen election monitoring is not “pure†crowdsourcing. We and others relied on establishing networks and offline meetings and coordination to build participation.

Another misconception is that every SMS number was targeted for the general public. Actually, the Map Kibera SMS line was and is primarily used by our volunteer reporters to send information from prearranged locations like polling stations. For the election, aside from our members, the Kibera Civic Watch Consortium sent in many reports during the election. The numbers are publicized to general residents, but operate mostly through carefully cultivated users.

I think there is a basic misconception that “crowdsourcing” something like election violence will happen with anonymous individuals. In tight-knit communities, this is simply not the case. They may text into a nationally publicized number, but those reports are not always the ones you want or can rely on. Verification is needed, which means local networks are still key. My hunch is that when people report through a local system the information is more likely to be accurate, because they know the faces behind the tech.

Particularly in more marginalized, insecure, or informal communities, people come together based on relationship networks, and being known and trusted as a leader in the community is an earned privilege that does not come easily nor is it taken lightly. People do not often trust something new that is introduced from “outside”.

National scale projects targeted to single events like elections should heavily support existing community level initiatives, and community-level initiatives around information need to be long-term investments into the community fabric. This means not just new technology projects which are still rare, but also traditional community media or data-driven local planning groups.

5) We’re still working out what works best in the space, so multiple projects are important for narrowing it down. A top-down model won’t work for citizen-based technology in emergencies, at least not for a long while.

While coordination and duplication avoidance is good, we are talking about places where the normal emergency response functions need supplementation and should be supplemented. I don’t know if a single top-down system for emergencies is ever going to work in Kenya, but it certainly hasn’t yet. I’ve seen way too many everyday crises happen with absolutely no response at all save for neighbors helping neighbors (and literally saving each others’ lives on a daily basis). In that sense people need access to options and a variety of ways to draw attention to and publicize an urgent situation. It’s also in the spirit of the technology world to keep trying out new ideas and iterating.

On the other hand, it’s true that some might irresponsibly publicize reporting channels that seem to promise response they can’t deliver, and technology is most certainly something we are now seeing organizations use to make themselves look good even at the expense of the public. We should ask whether there were unnecessary institutional barriers or unethical motivations to any lack of coordination or collaborative spirit, and direct our transparency lens that way. If competition for funding or funder requirements inhibited the social benefit of working together, as it usually does, then these incentive systems should be exposed. Also, the opportunism of pop-up and parachute technology projects just a week or so before the election is a distraction, and there were several of these as well. But what I think we’ve seen here is a partial triumph of civic collectivism over the usual silos created by the donor marketplace, which is why I’m seeing the glass as half-full. It could stand to be filled up all the way.

But here’s the most important trend that gives me hope:

7) A sea-change is underway in terms of how people engage with information in Kenya: they feel it’s their right and responsibility to speak out and to protect peace by countering rumor; and they increasingly feel they have tools with which to do so.

This is my hunch, but since 2009, I believe that the positive side of social media has had an impact in Kenya – or at least in Nairobi. I noticed during the election that people expected to be able to counter incorrect news and information sources by using their Facebook account or Twitter or one of the projects referenced here – they have grown used to reporting themselves and no longer rely exclusively on traditional media sources. When they see something happening, they expect someone local – if not themselves, then a neighbor – to be able to take a photo, send a message, somehow communicate.

This means that rumors can be countered more quickly, and leaves room for peace activists (most Kenyans) to organize and amplify accurate and helpful messages and at least contribute to the conversation, creating a more balanced discussion.

During these elections there was a new sense of the importance and responsibility that citizens have for being information collectors, transmitters, publicizers, verifiers, and the inkling that the standard channels of information aren’t the only ones that exist anymore – and that citizens have the responsibility to not only voice opinions but keep the rumors down, to participate in peace. Real crisis prevention has much more to do with local leadership, coordination, and behind the scenes response than the information that’s necessarily visible online. But that isn’t to say that creating visibility, keeping track of the truth and bringing information out of the dark in close to real time isn’t extremely valuable – it connects and inspires those who want to keep the peace and provides the opportunity for a local counter narrative to the dominant media.

Don’t risk missing the bigger story here: the simple act of residents recording actual ground level events themselves will have a long-term transformative impact on society – nowhere perhaps, as profoundly as in places like informal settlements.

This post originally appeared at Disruptive Witness.

Â

On citizen engagement and “feedback loopsâ€

Posted: January 28th, 2013 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, kenya, tech | Leave a comment »This post also appears on Disruptive Witness.

Citizen feedback on development and aid projects has been a kind of “holy grail†for aid for a few years now. The latest discussion comes in a recent blog post, “Consumer Reports for Aid“, by Dennis Whittle of the Center for Global Development. This is one of my very favorite topics, too. And, I eagerly sought the same kind of thing in 2009 when we began working in the Kibera community.

But here’s why we might be awaiting such feedback loops – in the model of Yelp or Consumer Reports – until the cows come home, dedicated hackathons notwithstanding.

When we tried to activate a citizen feedback loop in Kibera with Map Kibera, we thought that having a communication mechanism for residents to post comments about aid projects on the ground could revolutionize the way not only NGOs practiced, but the way the community viewed and took ownership over development. On Yelp, if I leave feedback, either positive or negative, I feel more connected to the businesses in my community and helping them succeed, fail or improve. In short, I feel a subtle sense of ownership. If the local NGOs and projects in a place like Kibera could be put online and rated by citizens, or various services commented upon in a detailed way, then maybe we’d have some real and meaningful feedback. USAID and big donors would respond to that, not to some puffed up self-reporting.

In fact, when we launched Voice of Kibera, that was one of the first ideas we had about what it might become. It wouldn’t necessarily be the news reporting site we have now; maybe it would allow people to mark services and organizations and comment on them.

It’s clear to me now why that didn’t happen – though, as you’ll see, we’re still working on the broader goal.

1) It’s hard to overestimate the complexity of a neighborhood of some 200,000 citizens, several tribes, a variety of languages, and little government whatsoever, that has existed in spite of the government’s desire to wipe it out and whose often transient residents have to struggle every day to make a living. I’m talking about one place, but I might be referring to many urban informal or extremely poor neighborhoods in the world which are the target of large amounts of aid dollars. There is a way things get done, and a reason why they get done that way – an entrenched system in which both the aid donors, government, and local actors play a role. People are very sensitive to the micropolitics that could impact their lives much more seriously than in wealthier environments. Offending the wrong person, or pleasing the right one is an important determinant of success.

Being in the business of engaging people, soliciting and publicizing their honest and informed views, and getting accurate data out there is a big job, and in my view far too little attention is being focused by techies or donors on the community side of this equation. Ultimately that’s what Map Kibera seeks to do, but it takes a lot more than setting up a web platform.

In this context, the role of a trusted representative is very important – who represents local opinion? Is it just whoever gets on Twitter while their neighbors still don’t have a mobile phone? In our excitement over technology there are always those who figure this out and can then hijack the process. System gaming problem? Not solved.

2) International aid is a mainstay of the Kibera and many other poor communities’ economies. This is what the international aid juggernaut has wrought. Yes, most Kiberans work outside of the aid industry and its various projects, but were you to do a critical analysis of the local economy and jobs, you would find that NGO jobs are the best paid and most stable, and come with a reputation upgrade, while “appreciations†– a soda at the end of a meeting, or a bit of airtime, cash or t-shirts – will be given out to a myriad of community members who attend any sort of event or meeting. Therefore, how do you build loyalty and good ratings on your Development Yelp? By intelligently executing a project that everyone relies upon day to day, that has impact, and legitimate sustainability (meaning the NGO jobs “should†be phased out eventually)? Or by winning a popularity contest by fitting the expectations for other perks? It’s a lot easier to do the latter. The incentives and potential rewards for supporting a claim that an NGO is doing great work are very high. Saying something negative can get you in trouble. We’re talking about tight-knit communities here. Why spend time giving critical feedback when it’s potentially going to get you in trouble?

3) In fact, why spend time giving feedback at all? Time and energy are very precious resources when you live in a place where parents are forced to leave small children to play unsupervised all day because they need to work and can’t pay for daycare. You’ll need to distribute some appreciation to get participation, unless participants are using a system for rating large-donor projects they’ve been beneficiaries of (see Danish Refugee Council example below), in which case much of the feedback might be in the form of calling out the continuing need for more assistance.

4) Many might respond that anonymizing this information will solve some of the problems I’ve mentioned. That’s essentially the route that Global Giving went with most of the stories on its Storytelling platform. But in that case, you don’t have very detailed knowledge about specific interventions or programs, which to me is the ultimate goal. Also, in most instances, asking for anonymous information from people is perhaps the purest yet least effective method of crowdsourcing. Anonymous inputs means you cannot hold people accountable for false information, and also removes a key incentive – to have an online presence and visibility. Even with Yelp, that’s clearly a motivator – a little bit of egotism.

So how do you make visible the inherent knowledge in a community of what works and what doesn’t? Certainly every Kibera resident has a lot of valuable knowledge, that, for instance, the vaunted bio-toilet is just stinking up the corner and no one’s using its supposed cooking gas. There is indeed a desire in Kibera, at least, to weed out the unproductive and even fake “briefcase†or “ghost†organizations that are supposed to reside there, but which aren’t in evidence on the ground, which means there is some latent incentive to provide data.

That’s why we hope our teams on the ground at Map Kibera and others like them will become the trusted informational resource for the community and will do a kind of due diligence on the local organizations and projects. In fact, this is a standard role that journalists play in a community – accountability and investigation. New kinds of citizen journalists and information centers can fill this role in places where there is limited news coverage. These informants aren’t anonymous at all – but they are protected by association with a network and local reputation.

In fact, an idea the Map Kibera team had was to create a directory of organizations and projects in the area where each group could have a page explaining what they do. The neutral nature of this project would invite in organizations in order to allow people to know who’s doing what where, and basic transparency would be built in. It would also help those tiny initiatives of regular community members – the orphanages, day cares, and youth groups – without much money or tech savvy to have some visibility and essentially prove their value. Mikel and I worked on this a little bit in a different format with Grassroots Jerusalem at www.grassrootsalquds.net. We are still seeking funding to finish this platform and establish it in Nairobi. Once that’s done, I think we can rely on our dedicated team to fact-check reports and post about various initiatives, and because they’re trusted members of the community, they can retrieve detailed opinions of citizens, both positive and negative and quote them on the site.

There is another way this could all work, which is to create a loop about government and large donor projects (those less likely to have a presence in the community) or simply highlight needs that require attention locally. This is more akin to the FixMyStreet concept, calling out local issues which have no project yet attached in hopes of triggering government or other support. We’ve tried to do this in Tandale, a slum in Dar es Salaam. There, we trained a team of reporters who’ve mapped the area and now post blog reports about conditions in the slum. See http://tandale.ramanitanzania.org/blog/. In this case, the loop has so far failed to close on the government or other responder’s side, in spite of initial promise. Here is where an influential third party can play an important role, such as the World Bank or UN.

I also found interesting this example of the Danish Refugee Council trying to solicit feedback on its work, which might not be a model to copy but gives a pretty accurate picture of what types of complaints a system might field. This is what a loop would often amount to: “We are requesting for power to charge our mobile phones, in order to reduce the challenges about the power and sent more SMS feedback.†Response: “According to your prioritization, DRC doesn’t provide electricity to any community.†Basically, that’s a no. I’m not sure that gets us much further, yet, than fielding such requests for more assistance. But, it does make public a normally very private exchange between donors and beneficiaries, when they are in that traditional relationship common to development schemes. I think this is a step in the right direction, because the more we open up these processes the more likely they will be open for questioning and productive critique.

The fact is that every “complaint†about “service delivery†is actually a citizen claiming a right – clean water, for instance – often in a place where there is no easy solution and there is a systemic and ultimately, political reason why neither NGOs nor government have yet to provide for such needs. Usually, that reason has little to do with the government (or big NGO/World Bank/UN etc) not knowing that the problem exists, sometimes in great detail.

The more that trustworthy community information representatives can detail and report and map and publicize and pressure and comment – and, do real journalism about – about the particular issue, the more likely that some downward accountability will be injected into the system. It’s also more likely that community members will begin to understand the forces at work in their neighborhoods and analyze what’s happening around them. It’s hard to imagine an information asymmetry as critical to address as that between residents of poor communities and major players in the development and government arenas, the 6 foot view vs the 30,000 foot.