Mapping Participatory Budgeting in Kenya’s Counties

Posted: March 13th, 2020 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: Accountability and Transparency, citizen feedback, Citizen Generated Data, Governance, kenya, openstreetmap, OSM, World Bank | Tags: Citizen Generated Data, Counties, Open Data, Participatory Budgeting | Leave a comment »

GroundTruth Initiative has been working for the past two years with three county governments in Kenya, along with partners the World Bank and Map Kibera Trust, to map and gather detailed feedback on county-funded projects. By training both county officials and local youth, while working cross-departmentally on data resources, GroundTruth has helped refine a process for citizen engagement which both increases transparency and accountability and provides much needed data and digital maps for the county.

In 2010, Kenya created a new constitution which focused on devolution of power to 47 new counties. Rather than focus development planning and budgets entirely at the national level, or in sub-regions which encompassed vastly different terrain and needs, the new constitution gave power to local officials and governors in the counties. Along with that came a need for new systems for finance and data. Starting up new processes and linking them to national systems was best done through digital means, but not all counties were ready technologically for these requirements.

In 2015, the World Bank began to support select counties to engage their citizens in a process of participatory budgeting. Citizens gathered in each subsection of the county, down to the village level, and prioritized the greatest needs. Budgeted projects included everything from new hospital wings to small dams and footbridges to new water points and classrooms. The process repeated each year, but it was difficult to track progress on the projects and to know where they were located so as to best allocate resources the following year. There were very few up to date digital or print maps showing county projects or pre-existing social resources and features.

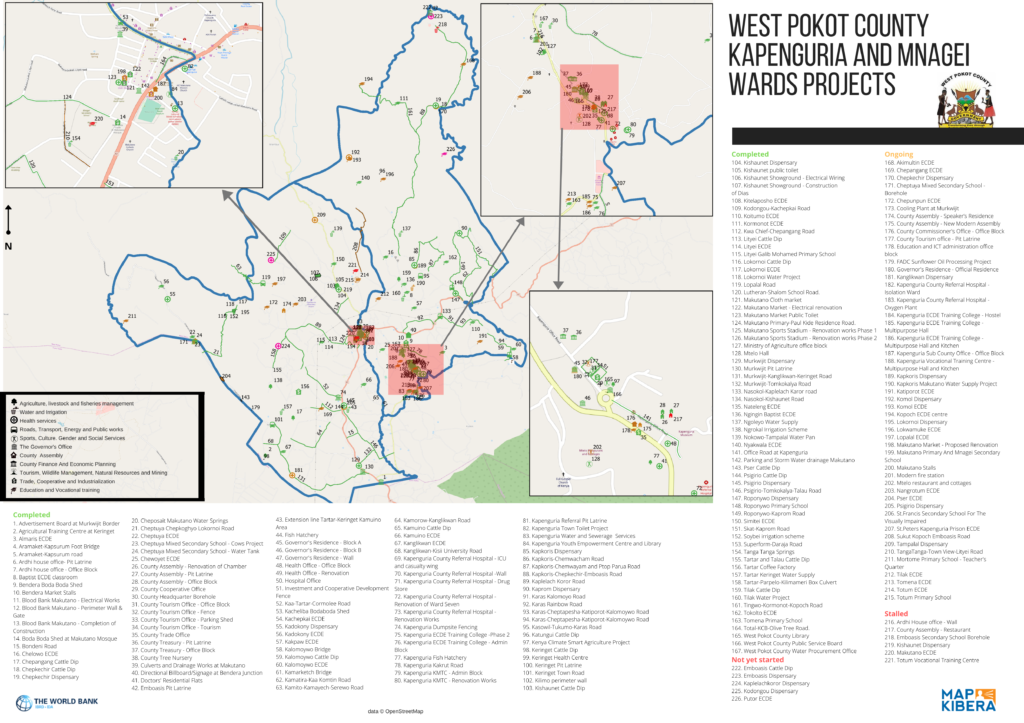

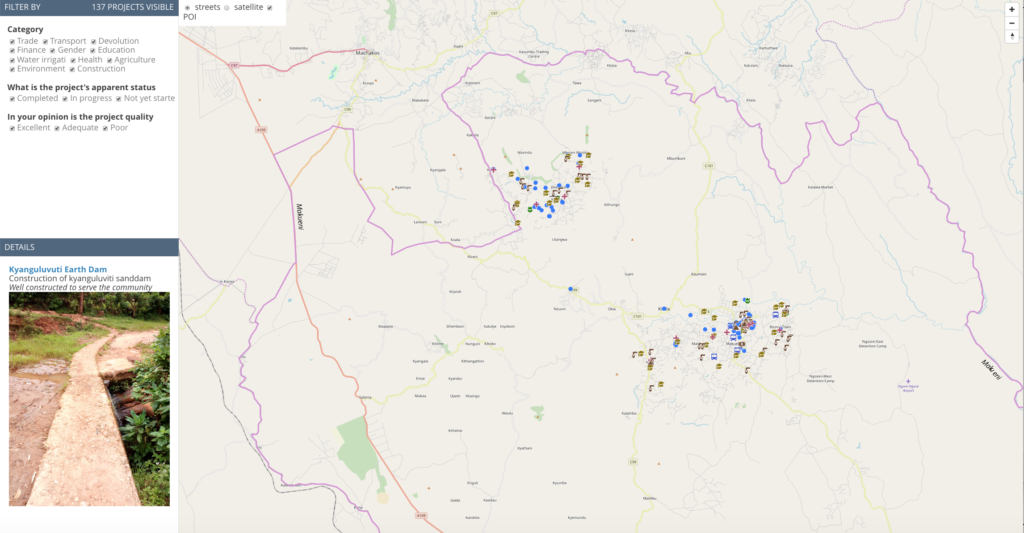

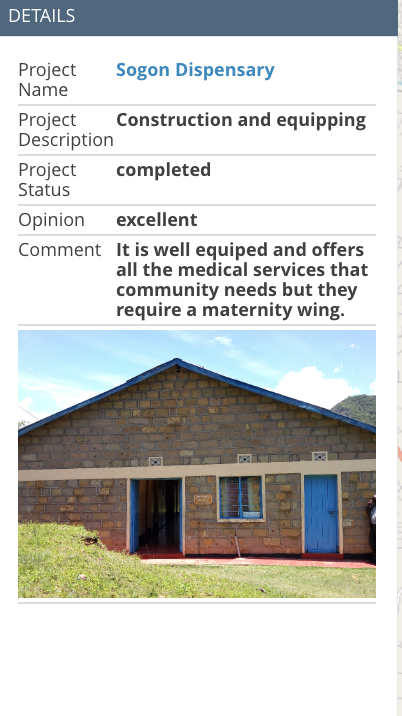

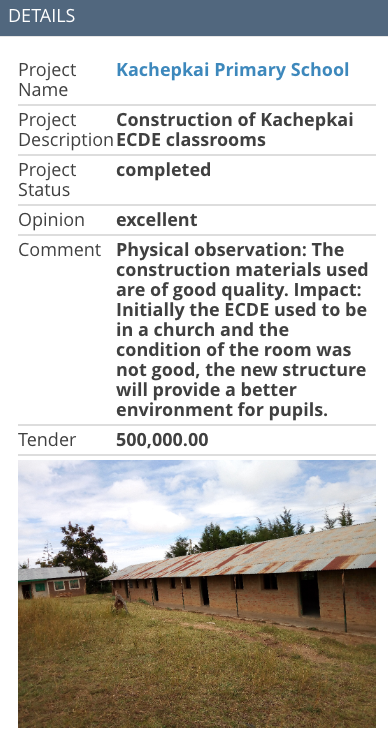

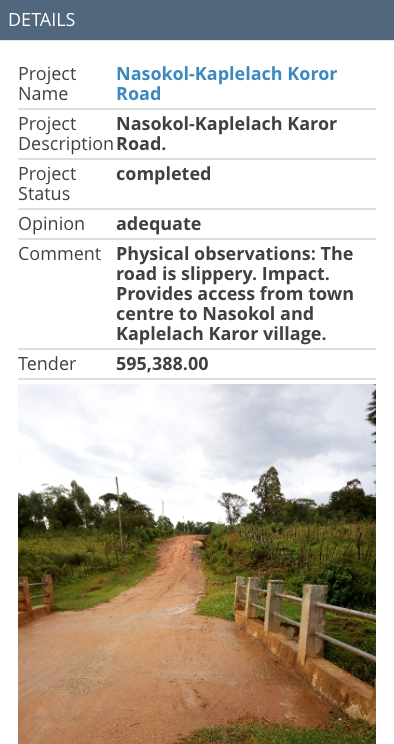

GroundTruth Initiative started working with counties in 2017 to help them create such maps. In partnership with Map Kibera Trust, GT worked with Makueni, Baringo, and West Pokot counties to use OpenStreetMap to develop a base map for their counties and map the county’s projects. As part of the process, county officials from Budgeting, M&E, Lands and Planning, ICT, and other departments were trained to use Open Data Kit and the Kobo Toolbox to survey their territory. In order to carry out the process efficiently and increase citizen involvement and project feedback, youth from each ward were also trained. Together, they not only mapped the project locations and basic details by visiting each project, but also photographed them and took notes on their completion status, operational status, and apparent quality.

This feedback was compiled by GroundTruth on a demonstration website for each county. The maps were also developed into print versions which could be used during the PB meetings themselves, and used and shared by officials who are often more comfortable with printed maps.

The work has paid off, as some counties have now completed a second phase of the project, receiving additional training on how to execute the process themselves and how to work with the data. All the maps and data stored in OpenStreetMap is open; the feedback on the projects is visible through the linked website. The purpose of the maps is to help the counties and the public to be able to track projects and budget expenditure. In the new phase of work completed in December 2019, budgeted contract amounts are also included on the site.

By working closely with both youth and government Data Fellows, Map Kibera and GroundTruth are currently supporting the counties to continue to utilize the process and better integrate it with their finance, M&E and planning departments, and work with their new GIS officers. Meanwhile, other counties are looking to work with the same process. The future of devolved governance and citizen accountability through mapping looks bright.

How to Improve Innovation Funding: lessons from the MakeSense project

Posted: June 17th, 2016 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, Funding, Sensors | Leave a comment »

MakeSense was meant to test feedback loops from “citizen-led sensor monitoring of environmental factors†in the Brazilian Amazon, providing structured, accurate and reliable data to compare against government measurements and news stories in the Amazon basin. The project centered around developing, manufacturing and field testing DustDuino sensors already prototyped by Internews, and developing a dedicated site to display the results at OpenDustMap.

It may seem obvious that it was too ambitious to try to create a mass-produced hardware prototype with two types of connectivity, a documenting website, do actual community engagement and testing (in the Amazon) AND do further business development, all for $60,000, not to mention the coordination required. But, it is also true that typical funds available for innovation lend themselves to this kind of overreach.

Good practice would be to support innovators throughout the process, including (reasonable) investment in team process (while still requiring real-life testing and results), and opportunities for further fundraising based on “lessons†and redesign from a first phase. As well, an expectation that the team be reconfigured, perhaps losing some members and gaining others between stages, plus defining a clear leadership process.

Supportive and intensive incubation, with honest assessment built in through funding for evaluations such as the one we published for this project would go a long way toward better innovation results.

Funders should also require transparency and honest evaluation throughout. If a sponsored project or product cannot find any problems or obstacles to share about publicly, they’re simply not being honest. Funders could go a long way toward making this kind of transparency the norm instead of the exception. In spite of an apparent “Fail Fairâ€-influenced acculturation toward embracing failure and learning, the vast majority of projects still do not subject themselves to any public discussion that goes beyond salesmanship. This is often in fear of causing donors to abandon the project. Instead, donors could find ways to reward such honest self-evaluation and agile redirection.

Learning from the MakeSense DustDuino Air Quality Sensor Pilot in Brazil

Posted: May 5th, 2016 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, Sensors, tech | Tags: DustDuino, MakeSense | Leave a comment »Introducing new technology in international development is hard. And all too often, the key details of what actually happened in a project are hidden — especially when the project doesn’t quite go as planned. As part of the MakeSense project team, we are practicing transparency by sharing all the twists, turns and lessons of our work. We hope it is useful for others working with sensors and other technology, and inspires greater transparency overall in development practice.

Please have a look at GroundTruth’s complete narrative history of the MakeSense pilot here on Medium, or download a PDF of the full report here.Â

The MakeSense project was supported by Feedback Labs and the project team included GroundTruth, Internews, InfoAmazonia, Frontline SMS/ SIMLab, and Development Seed. MakeSense was meant to test feedback loops from “citizen-led sensor monitoring of environmental factors” in the Brazilian Amazon, providing structured, accurate and reliable data to compare against government measurements and news stories in the Amazon basin. Over the course of the project, DustDuino air quality sensor devices were manufactured and sent to Brazil. However, the team made several detours from the initial plan, and ultimately we were not able to fulfill our ambitious goals. We did succeed in drawing some important learnings from the work.

Lessons Learned:

Technical Challenges

- Technical Difficulties are to be expected

Setting up a new hardware is not like setting up software: when something goes wrong, the entire device may have to go back to the drawing board. Delays are common and costly. This should be expected and understood, and even built into the project design, with adequate developer time to work out bugs in the software as well as hardware. At the same time, software problems also require attention and resources to work out which became an issue for this project as well, which often relied upon volunteer backup technical assistance.

- Simplify Technical Know-how Required for Your Device

The project demonstrated that it is important to aim for the everyday potential user as soon as possible. The prototype, while mass-produced, still required assembly and a slight learning curve for those not familiar with its components, and also needed some systems maintenance in each location. Internews plans for the DustDuino’s next stage to be more “Plug-and-playâ€â€Šâ€” most people don’t have the ability to build or troubleshoot a device themselves.

- Consider Data Systems in Depth

This project suffered from a less well-thought-out data and pipeline system, which required much more investment than initially considered. For instance, the sensor was intended to send signals over either Wi-Fi or GSM, but the required code for the device itself, and the destination of the data shifted throughout the project. Having a working data pipeline and display online consumed a great deal of project budget and ultimately stalled.

- Prioritize Data Quality

The production of reliable data, and scientifically valid data, also needs to be well planned for. This pilot showed how challenging it can be to get enough data, and to correct issues in hardware that may interfere with readings. Without this very strong data, it is nearly impossible to successfully promote the prototype, much less provide journalists and the general public with a tool for accountability.

Implementation

It is important to be intentional about technical vs programmatic allocation, and not underestimate the need for implementation funding. It is often the case that software and hardware development use up the majority of a grant budget, while programmatic and implementation or field-based design “with†processes get short shrift in the inception phase. Decision making about whether to front-load the technology development or to develop quick but rough in order to get prototypes to the field quickly, as referenced in the narrative, should be made intentionally and consciously. Non-technical partners or team members should be aware of the incentives present for technical team members to emphasize hardware/software development over often equally critical local engagement and field testing processes, and ideally have an understanding of the basic technical project requirements and operations. This project suffered from different understandings of this prioritization and timeline.

Funding Paralysis

The anticipation of a need for future funding dominated early conversations, highlighting a typical bind: funding available tends to skew to piloting with no follow-up opportunities for successful pilots. This means that before the pilot even produces its results, organizations must begin to source other funds. So, they must allocate time to business development as well, which can be difficult if not impossible, and face pressure to create marketing materials and other public relations pieces. This can also in some cases (although not with this pilot) lead to very premature claims of success and a lack of transparency. During this project, there was some disagreement among team members about how much to use this pilot fund to support the search for further investment — almost as a proposal development fund — and how much to spend on the actual proof of concept through hardware/software development and field testing.

This is a lesson for donors especially: when looking for innovative and experimental work, include opportunities for scale-up and growth funding or have a plan in mind for supporting your most successful pilots.

Teamwork

A consortium project is never easy. A great deal of time is required simply to bring everyone to the same basic understanding of the project. This time should be adequately budgeted for from the start. Managing such a team is a challenge, and experienced and very highly organized leadership helps the process. FrontlineSMS (which received and managed the funding from Feedback Labs) specifically indicated they did not sufficiently anticipate this extensive requirement. Also, implementing a flat structure to decision making was a huge challenge for this team. Though it was in the collective interest to achieve major goals, like follow-on funding, community engagement, and a working prototype, there were no resources devoted to coordinating the consortium nor any special authority to make decisions, sometimes leading to members operating at cross purposes. Consistent leadership was lacking, while decision-making and operational coordination were very hard given quite divergent expectations for the project and kinds of skills and experience. This is not to say that consortium projects are a poor model or teams should not use a flat structure, but that leading or guiding such a team is a specialty role which should be well considered and resourced.

Part of the challenge in this case was that the lead grantee role in the consortium actually shifted in 2015 from FrontlineSMS to SIMLab, its parent company, when the FrontlineSMS team were spun out with their software at the end of 2014. The consortium members were largely autonomous, without regular meetings and coordination until July 2015, when SIMLab instituted monthly meetings and more consistent use of Basecamp.

Communications

Set up clear communications frameworks in advance, including bug reporting mechanisms as well as correction responsibilities. Delays in reporting bugs with Development Seed and FrontlineSMS APIs contributed significantly to the instability of the sensors in the field. Strong information flow about problems, and speedy remote decision-making, was never really achieved. At the same time, efficiency in such consortia is paramount, so that time isn’t taken from operational matters with coordination meetings — so a balance must be struck. This project eventually successfully incorporated the use of BaseCamp.

What is the Logical Conclusion for Feedback Systems?

Posted: November 6th, 2014 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback | Tags: Feedback Labs, M&E, Open Schools Kenya | Leave a comment »I’ll confess, I’ve never been a huge fan of M&E. While I absolutely love the data and statistics and numbers and fascinating insights of a good evaluation, as the founder of a nonprofit in Kenya, Map Kibera, doing a quality job on monitoring and much less evaluation was daunting.

Not only because we were under-resourced, and lacked high staff capacity (our members all coming from the Kibera slum) – but Map Kibera was actually set up in part to counter a problem obvious to any Kibera resident. NGOs and researchers were constantly collecting data, but then were usually never seen or heard from again.

Where Does the Data Go?

Was that data even seen again by the collecting organization after their project reports were turned in? What good was all that time and energy spent – on the part of the organization, but more importantly on the part of the good citizens of Kibera, who were tired of answering questions about their income and toilet habits three times in one week? And didn’t they have a right to access the resulting information as well?

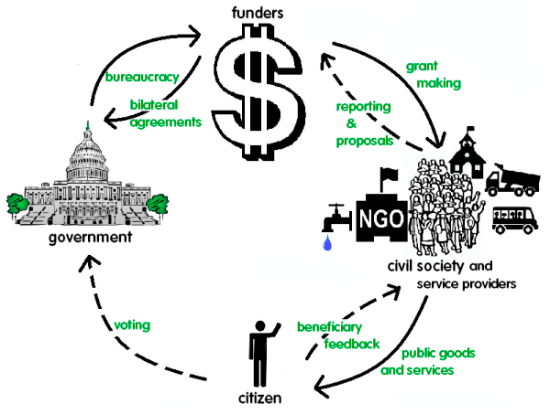

Now many organizations, including Map Kibera, our organization GroundTruth Initiative, and others such as the panelists who joined me at the M&E Tech Feedback Loops Plenary: Labor Link, Global Giving, and even the World Bank have put an emphasis on citizen feedback as the core of a new way of doing development.

It’s possible to imagine a world where some of the main reasons for doing monitoring and evaluation are shifted over to citizens themselves – because they want to hold to account both governmental and non-governmental organizations so that the services not only get to the right people, but those people can drive the agenda for what’s needed where.

While a complicated study on, say, the school system and education needs of Kibera people might provide insight, if it sits on a shelf and doesn’t inspire grassroots pressure to shift priorities and improve education, what is the use of it? Why not instead invest in efforts to collect open data on education jointly with citizens, like our Open Schools Kenya initiative?

The benefit here is that the information is open and collectively tended – meaning kept up to date, shared, made comparable with other data sets (like Kenya’s Open Data releases from the government), and used for more than just one isolated study. It’s a way for the community to assess the status of local education itself. In our own neighborhoods and school systems, we wouldn’t have it any other way.

A Citizen Led Future

As noted by Britt Lake of Global Giving on our panel discussion, taking this concept to its logical conclusion there would be a loss of control by development agencies. Is this the real hurdle to citizen-led data collection? To what extent can aid systems be devolved to the people who are meant to primarily benefit?

A truly forward-thinking organization would embrace this shift, because with better information being collected and used at the grassroots, there will be more aid transparency overall and less opportunity for gaming the system. If you think that no small CBO has ever submitted a bogus progress report which went up the chain at USAID, think again.

Nowhere in this system is there incentive to give an accurate account of failures or document intelligent but unpredicted programmatic adaptations and detours that were made. Yet if there’s one thing I know the Kibera people want, it’s for the many organizations they see around them in the slum to be held accountable for all the funds they receive, and for delivering on their years of promises for improving the slum.

In fact, transparency around aid at this hyperlocal level is something we should even feel an ethical obligation to provide. Here’s hoping that in 20 years, the impact of the open data and feedback movements will mean that public information about projects done in the public good is reflexively open and responsive, and M&E as a separate and often neglected discipline is a thing of the past.

This post was originally featured on ICT Works as a Guest Post.

Making Education Information Available to All in Kibera

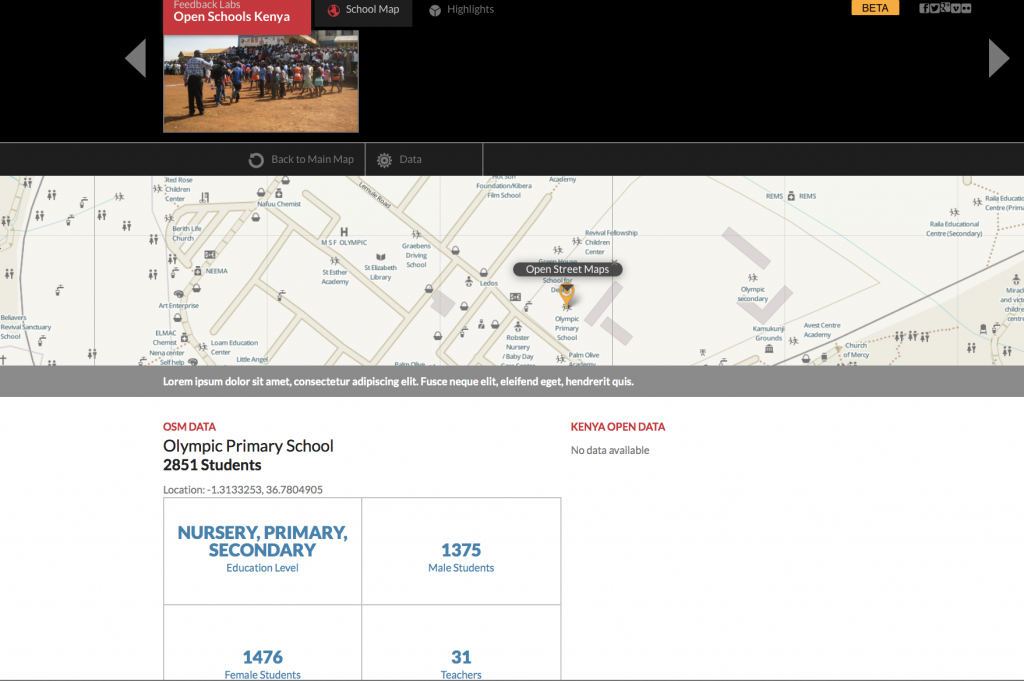

Posted: July 9th, 2014 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, kenya, openstreetmap | Tags: education, Feedback Labs, Gates Foundation | 1 Comment »How can all the information about Kenyan schools, including data released by the Kenyan government, and citizen mapping, have a greater impact on education? We’ve been working for the past few months on a project to make information about schools much more available and useful in Kenya. It’s a joint operation between GroundTruth Initiative, Map Kibera, Development Gateway, Feedback Labs, and the Gates Foundation among others.

Many people collect information about education – and they sometimes make it open and free to use. So, why isn’t it easy to find information about a particular school – for a parent, or for an education researcher? Much of the information that’s out there isn’t connected to the other data – and especially when it comes to informal schools, which provide a great deal of the education services in places like informal settlements.

Citizen data – like mapping schools using OpenStreetMap – should also be easy to combine and compare with official education data. And finally, all this info could be accessible and useful to everyone from parents to policymakers.

So, we’ve started with Kibera as a test location for the Open Schools Kenya project.

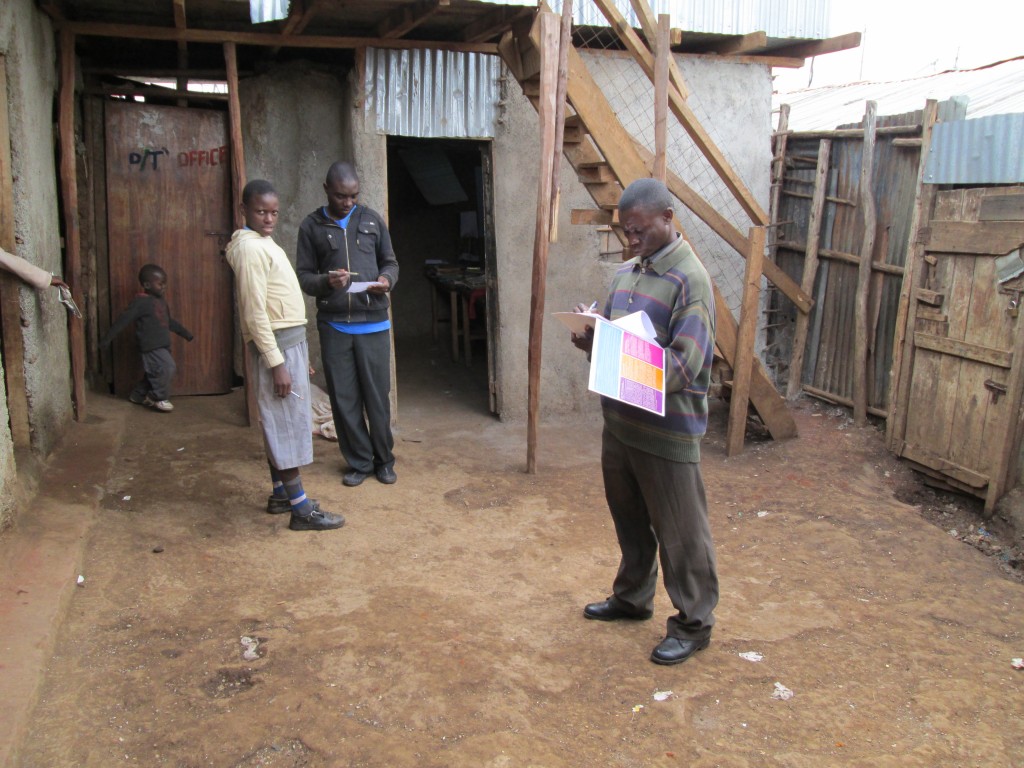

Over the past few months, the Map Kibera team has engaged parents, school leaders, and education officials in Kibera to find out how the informal school sector can be more visible, and to assess the demand for information on education. Now, a widespread effort is underway by Map Kibera to make sure that the schools data that the team collected a few years ago is still accurate, and to add new info as well. We’re also collecting photos of each school, no matter how small. Every one will have a page on the website, really bringing the informal school sector to light. Formal schools in Kibera will be there too.

Much of the work so far has been around engaging important leaders in the community, who care about local kids getting the best education. Mikel Maron of GroundTruth was recently in Nairobi working on the project and will be updating in a separate post about this busy trip. Ultimately, the community wants to know more about its schools, and to improve them. So do education supporters throughout Kenya.

But beyond this important mission of organizing and making interoperable many data sets across the vast education sector in Kenya, we’re also working on an ambitious hypothesis: that parents and community leaders in education will want to provide feedback on schools, which in turn will inform policy and improve individual schools. Ultimately, our platform will be a place where people can not only be consumers of information, but will provide their own opinions and suggestions on schools, and, importantly, submit corrections and updates to the data on the site. Given the early positive response to these ideas, we’re optimistic that this will be possible in Kibera and also Kenya-wide.

The project is not just about education, either. It has far-reaching potential in other sectors as well. We hope to demonstrate that citizen data, official data, academic research and more can come together and be part of a conversation with those on the ground who feel the impact most of government policy in every sector – ordinary citizens. And, that this kind of conversation means that people “own†their own information, and we can see the beginnings of a true “feedback loop†or dialogue between citizens and government, through the medium of shared data.

This article was originally posted on the Map Kibera blog, July 3, 2014.