Learning from the MakeSense DustDuino Air Quality Sensor Pilot in Brazil

Posted: May 5th, 2016 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, Sensors, tech | Tags: DustDuino, MakeSense | Leave a comment »Introducing new technology in international development is hard. And all too often, the key details of what actually happened in a project are hidden — especially when the project doesn’t quite go as planned. As part of the MakeSense project team, we are practicing transparency by sharing all the twists, turns and lessons of our work. We hope it is useful for others working with sensors and other technology, and inspires greater transparency overall in development practice.

Please have a look at GroundTruth’s complete narrative history of the MakeSense pilot here on Medium, or download a PDF of the full report here.Â

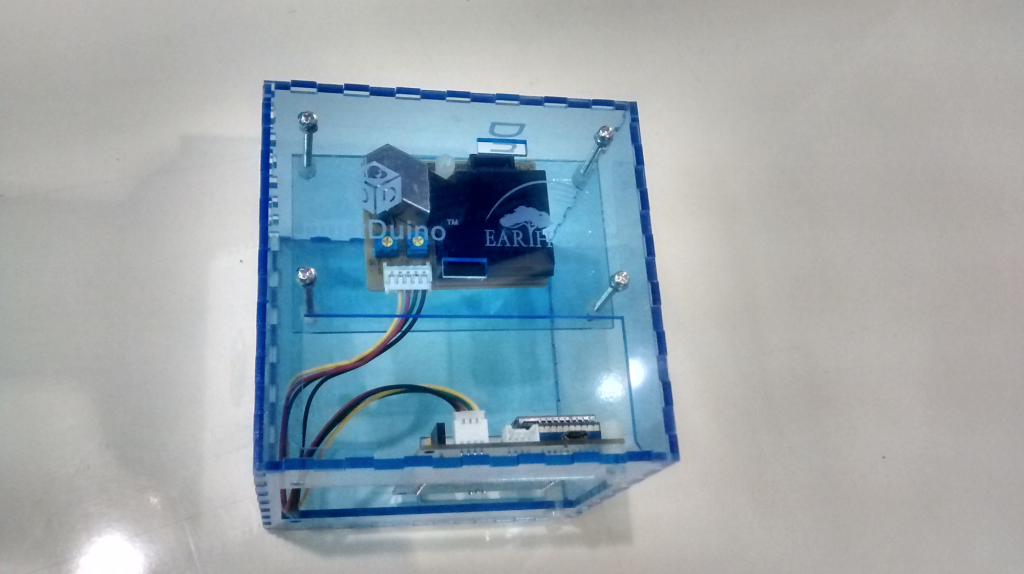

The MakeSense project was supported by Feedback Labs and the project team included GroundTruth, Internews, InfoAmazonia, Frontline SMS/ SIMLab, and Development Seed. MakeSense was meant to test feedback loops from “citizen-led sensor monitoring of environmental factors” in the Brazilian Amazon, providing structured, accurate and reliable data to compare against government measurements and news stories in the Amazon basin. Over the course of the project, DustDuino air quality sensor devices were manufactured and sent to Brazil. However, the team made several detours from the initial plan, and ultimately we were not able to fulfill our ambitious goals. We did succeed in drawing some important learnings from the work.

Lessons Learned:

Technical Challenges

- Technical Difficulties are to be expected

Setting up a new hardware is not like setting up software: when something goes wrong, the entire device may have to go back to the drawing board. Delays are common and costly. This should be expected and understood, and even built into the project design, with adequate developer time to work out bugs in the software as well as hardware. At the same time, software problems also require attention and resources to work out which became an issue for this project as well, which often relied upon volunteer backup technical assistance.

- Simplify Technical Know-how Required for Your Device

The project demonstrated that it is important to aim for the everyday potential user as soon as possible. The prototype, while mass-produced, still required assembly and a slight learning curve for those not familiar with its components, and also needed some systems maintenance in each location. Internews plans for the DustDuino’s next stage to be more “Plug-and-playâ€â€Šâ€” most people don’t have the ability to build or troubleshoot a device themselves.

- Consider Data Systems in Depth

This project suffered from a less well-thought-out data and pipeline system, which required much more investment than initially considered. For instance, the sensor was intended to send signals over either Wi-Fi or GSM, but the required code for the device itself, and the destination of the data shifted throughout the project. Having a working data pipeline and display online consumed a great deal of project budget and ultimately stalled.

- Prioritize Data Quality

The production of reliable data, and scientifically valid data, also needs to be well planned for. This pilot showed how challenging it can be to get enough data, and to correct issues in hardware that may interfere with readings. Without this very strong data, it is nearly impossible to successfully promote the prototype, much less provide journalists and the general public with a tool for accountability.

Implementation

It is important to be intentional about technical vs programmatic allocation, and not underestimate the need for implementation funding. It is often the case that software and hardware development use up the majority of a grant budget, while programmatic and implementation or field-based design “with†processes get short shrift in the inception phase. Decision making about whether to front-load the technology development or to develop quick but rough in order to get prototypes to the field quickly, as referenced in the narrative, should be made intentionally and consciously. Non-technical partners or team members should be aware of the incentives present for technical team members to emphasize hardware/software development over often equally critical local engagement and field testing processes, and ideally have an understanding of the basic technical project requirements and operations. This project suffered from different understandings of this prioritization and timeline.

Funding Paralysis

The anticipation of a need for future funding dominated early conversations, highlighting a typical bind: funding available tends to skew to piloting with no follow-up opportunities for successful pilots. This means that before the pilot even produces its results, organizations must begin to source other funds. So, they must allocate time to business development as well, which can be difficult if not impossible, and face pressure to create marketing materials and other public relations pieces. This can also in some cases (although not with this pilot) lead to very premature claims of success and a lack of transparency. During this project, there was some disagreement among team members about how much to use this pilot fund to support the search for further investment — almost as a proposal development fund — and how much to spend on the actual proof of concept through hardware/software development and field testing.

This is a lesson for donors especially: when looking for innovative and experimental work, include opportunities for scale-up and growth funding or have a plan in mind for supporting your most successful pilots.

Teamwork

A consortium project is never easy. A great deal of time is required simply to bring everyone to the same basic understanding of the project. This time should be adequately budgeted for from the start. Managing such a team is a challenge, and experienced and very highly organized leadership helps the process. FrontlineSMS (which received and managed the funding from Feedback Labs) specifically indicated they did not sufficiently anticipate this extensive requirement. Also, implementing a flat structure to decision making was a huge challenge for this team. Though it was in the collective interest to achieve major goals, like follow-on funding, community engagement, and a working prototype, there were no resources devoted to coordinating the consortium nor any special authority to make decisions, sometimes leading to members operating at cross purposes. Consistent leadership was lacking, while decision-making and operational coordination were very hard given quite divergent expectations for the project and kinds of skills and experience. This is not to say that consortium projects are a poor model or teams should not use a flat structure, but that leading or guiding such a team is a specialty role which should be well considered and resourced.

Part of the challenge in this case was that the lead grantee role in the consortium actually shifted in 2015 from FrontlineSMS to SIMLab, its parent company, when the FrontlineSMS team were spun out with their software at the end of 2014. The consortium members were largely autonomous, without regular meetings and coordination until July 2015, when SIMLab instituted monthly meetings and more consistent use of Basecamp.

Communications

Set up clear communications frameworks in advance, including bug reporting mechanisms as well as correction responsibilities. Delays in reporting bugs with Development Seed and FrontlineSMS APIs contributed significantly to the instability of the sensors in the field. Strong information flow about problems, and speedy remote decision-making, was never really achieved. At the same time, efficiency in such consortia is paramount, so that time isn’t taken from operational matters with coordination meetings — so a balance must be struck. This project eventually successfully incorporated the use of BaseCamp.

OSM: Mapping Power to the People?

Posted: June 5th, 2015 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: OSM, tech | Tags: Community, data, future of OSM, power | 2 Comments »As you probably know, OpenStreetMap is a global project to create a shared map of the whole world. A user-created map, that is. Of course, in a project where anyone can add their data, there are many forms this can take, but the fundamental idea allows for local ownership of local maps — a power shift from the historical mapping process. Now, if I want to add that new cafe in my neighborhood to the OSM map, I can do it, and quickly. And I don’t have to worry that I’m giving away my data to a corporate behemoth like Google — open and free means no owner.

But lately I’ve noticed a trend away from the radical potential of such hyperlocal data ownership, as OSM gets more widely used and recognized, inspiring everyone from the White House to the Guardian to get involved in remote mapping (using satellite imagery to trace map details onto OSM, like roads and building outlines). But remote activities still require people who know the area being mapped to add the crucial details, like names of roads and types of buildings. So why is the trend worrying?

Since first training 13 young people in the Kibera slum to map their own community using OSM, in 2009, I have focused quite a bit on questions of the local — where things actually happen. And the global aid and development industry, as anyone can see who has worked very closely with people anywhere from urban slums to rural villages, tends to remain an activity that begins in Washington (or at best, say, Nairobi’s glassy office buildings) and ends where people actually live. Mapping, on the other hand, is an activity that is inherently the other way around — best and most accurately done by residents of a place. And, I would argue, mapping can therefore actually play a role in shifting this locus of decision making.

More poetically perhaps, I also see maps as representations of who made them rather than a place per se. So if the community maps itself, that’s what they see. And that can shift the planning process to highlight something different — local priorities. After all, a resident of a place knows things faster, and better, than any outsider, and new technology can in theory highlight and legitimize this local knowledge. But just as easily, it seems, it can expedite data extraction.

Even more importantly, as any social scientist will tell you, a resident of a place knows the relevant meaning and context of the “facts†that are collected — the story behind the data. An outsider often has no idea what they’re actually looking at, even if it seems apparent. (An illustrative anecdote: I was recently in Dhaka and we noticed a political poster with a tennis racket symbol. We wondered why use a tennis racket to represent this candidate? That’s not a tennis racket — it’s a racket-shaped electric mosquito zapper, said one Bangladeshi. What you think you see is not the reality that counts!)

So, when the process of mapping gets turned around — with outlines done first by remote tracing and locals left to “fill in the blanks†for those outside pre-determined agendas, that sense of prioritization is flipped. In spite of attempts to include local mappers, needs are often focused on the external (usually large multilateral) agency, leaving just a few skilled country residents to add names to features in places they’ve never set foot in before.

There are degrees of local that we are failing to account for. Thinking that once we’ve engaged anyone “local†(ie, non-foreign) in a mapping project we’ve already leveled the playing field is letting ourselves off the hook too easily. By painting the local with one brush we fail to engage people within their own neighborhood (not to mention linguistic, ethnic group or gender). We underestimate the power of negative stereotypes in every city and country against those in the direst straits, including pervasive ideas of lack of ability, tech or otherwise. This is especially problematic when dealing with the complex dynamics of urban slums, in my experience. But any place where we hope to eventually inspire a cadre of local citizen mappers who care about getting the (data) story right, it’s crucial to diversify.

Having dealt with these challenges nearly from day one of Map Kibera, I’m particularly sensitive to the question “How does a map help the people living in the place represented?†You might say that development agencies and governments have a clear aim for their maps that will help in very important ways. Therefore, a faster and more complete map from a technical standpoint is always better. (Indeed, getting support for open maps in the first place is quite an achievement). But more often than you’d think, the map seems to be made for its own sake or to have a quick showpiece.

Even if our answer is that the map would help if disaster struck, that seems to be missing the point and might not even be true in most cases. Strong local engagement and leadership are said to be “best practice†even in cases of disaster response and preparedness, though they aren’t yet the norm. Since the recent earthquake in Nepal, there has been a very successful mapping response thanks to local OSMers Kathmandu Living Labs. But critically, this group had been working hard locally for some time. And we should see this as a great starting point for widespread engagement, not an end product.

Another problem is that established mapping processes in the field aren’t questioned much, even when it comes to OSM. Since mapping is often something people do who are techies of some kind — GIS people, programmers, urban planners — organizers sometimes seem to forget to simplify to the lowest common denominator needed for a project. Does the project really need to use several types of technological tools and collect every building outline? Does every building address need to be mapped? If not, it just seems like an easy win — why not collect everything? One reason not to is because later when you find you need local buy-in, even OSM may be viewed as an outsider project meant to dominate a neighborhood, a city, especially in sensitive neighborhoods where this has indeed been a primary use of maps. I wonder if people will one day want to create “our map†separately from OSM. A different global map wiki which is geared toward self-determination, perhaps? That would be a major loss for the OSM community.

Perhaps I seem stuck on questions of “whose map†and “by whom, for whom?†Well, that’s what intrigued me about OSM in the first place. We used to talk a lot about the democratizing potential of the internet, about wikis and open source as a model for a new kind of non-hierarchical online organizing. Now, it’s clear that because of low capacity and low access, it’s actually pretty easy to bypass the poor, the offline, the unmapped. And because of higher capacity among wealthier professionals and students in national capitals globally, it’s easier for them to do the job of mapping their country instead. Of course there isn’t anything wrong with people coming together digitally over thousands of miles to create a map. In an idealistic sense it’s a beautiful thing.

But the fact is, we (that is, technologists and aid workers — both foreign and not) still tend to privilege our own knowledge and capacity far and away over that of the people we are seeking to help. We can send messages to the poor through a mobile phone, strategize on what poster to put up where, but the survey to figure out who lives there and what they care about? Still done by outsiders, hiring locals only as data extractors. As knowledge and expertise used to make decisions becomes more data-driven and complex, a class of expert and policy maker is created that is even more out of reach. Access has always been messy. Now (thanks in part to mobile phone proliferation and without much further analysis), we hardly talk about access anymore. The fad has shifted to “big data†and other tech uses at the very top.

To me, OSM was always so much more than just a place where people shared data. It was one small way to solve this problem of invisibility bestowed by poverty.

The possibilities of OSM to empower the least powerful are still tantalizingly close on the horizon. With just a few tweaks to existing thinking, I hope we can tip the scale — we can prioritize the truly local and allow the global to serve it. But to do so we must resist glib and lazy thinking around how those processes actually work. We must pay attention to order of operations (who maps first? whose data shows up as default?), and subtleties of ownership and buy-in, and we must examine who we think of as “localâ€.

But most of all, and most simply, we have to reorient our thinking in designing mapping projects. It could be quite straightforward, for instance:

- integrating more localized thinking into training courses and OSM materials, suggesting that people on the margins (such as slumdwellers) can and should be learning OSM tools as well;

- training people to think about social context and local priorities not just technology;

- doing more offline outreach and print map distribution; creating new map renderings highlighting levels of local and remote mapping;

- making it the norm that residents of a neighborhood be involved in early project planning;

- engaging with people who have long done offline forms of data gathering and mapping in their communities.

- Considering that first pass on a blank map might matter.

- And considering that leading local technical mappers start to conceptualize their roles more as mentors to communities and to new mappers in those places than as expert consultants to foreign organizations. I’ve seen the light bulb go on when that happens.

Yes, ultimately, we will do best to address the incentive structures of international funding which are keeping us from achieving what we’d all undoubtedly wish to see, which is everyone getting the opportunity to put themselves on the map.

Many will say that it is just too hard, too time consuming, too cumbersome, too expensive, too — something — to really prioritize local in the way I’m talking about. We’ll never hit “scale†for instance. Something needs to be done now. But I would ask you to reconsider. I believe that in fact, sensitive and thoughtful engagement with communities is the only real path to scale and sustainability for many kinds of “crowd-†or “citizen-†based data work that is now happening, and most certainly the only way to reach the real target of any development-oriented data effort — actual improvements in the lives of the world’s poor and marginalized.

This post also appears here on Medium.

On citizen engagement and “feedback loopsâ€

Posted: January 28th, 2013 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, kenya, tech | Leave a comment »This post also appears on Disruptive Witness.

Citizen feedback on development and aid projects has been a kind of “holy grail†for aid for a few years now. The latest discussion comes in a recent blog post, “Consumer Reports for Aid“, by Dennis Whittle of the Center for Global Development. This is one of my very favorite topics, too. And, I eagerly sought the same kind of thing in 2009 when we began working in the Kibera community.

But here’s why we might be awaiting such feedback loops – in the model of Yelp or Consumer Reports – until the cows come home, dedicated hackathons notwithstanding.

When we tried to activate a citizen feedback loop in Kibera with Map Kibera, we thought that having a communication mechanism for residents to post comments about aid projects on the ground could revolutionize the way not only NGOs practiced, but the way the community viewed and took ownership over development. On Yelp, if I leave feedback, either positive or negative, I feel more connected to the businesses in my community and helping them succeed, fail or improve. In short, I feel a subtle sense of ownership. If the local NGOs and projects in a place like Kibera could be put online and rated by citizens, or various services commented upon in a detailed way, then maybe we’d have some real and meaningful feedback. USAID and big donors would respond to that, not to some puffed up self-reporting.

In fact, when we launched Voice of Kibera, that was one of the first ideas we had about what it might become. It wouldn’t necessarily be the news reporting site we have now; maybe it would allow people to mark services and organizations and comment on them.

It’s clear to me now why that didn’t happen – though, as you’ll see, we’re still working on the broader goal.

1) It’s hard to overestimate the complexity of a neighborhood of some 200,000 citizens, several tribes, a variety of languages, and little government whatsoever, that has existed in spite of the government’s desire to wipe it out and whose often transient residents have to struggle every day to make a living. I’m talking about one place, but I might be referring to many urban informal or extremely poor neighborhoods in the world which are the target of large amounts of aid dollars. There is a way things get done, and a reason why they get done that way – an entrenched system in which both the aid donors, government, and local actors play a role. People are very sensitive to the micropolitics that could impact their lives much more seriously than in wealthier environments. Offending the wrong person, or pleasing the right one is an important determinant of success.

Being in the business of engaging people, soliciting and publicizing their honest and informed views, and getting accurate data out there is a big job, and in my view far too little attention is being focused by techies or donors on the community side of this equation. Ultimately that’s what Map Kibera seeks to do, but it takes a lot more than setting up a web platform.

In this context, the role of a trusted representative is very important – who represents local opinion? Is it just whoever gets on Twitter while their neighbors still don’t have a mobile phone? In our excitement over technology there are always those who figure this out and can then hijack the process. System gaming problem? Not solved.

2) International aid is a mainstay of the Kibera and many other poor communities’ economies. This is what the international aid juggernaut has wrought. Yes, most Kiberans work outside of the aid industry and its various projects, but were you to do a critical analysis of the local economy and jobs, you would find that NGO jobs are the best paid and most stable, and come with a reputation upgrade, while “appreciations†– a soda at the end of a meeting, or a bit of airtime, cash or t-shirts – will be given out to a myriad of community members who attend any sort of event or meeting. Therefore, how do you build loyalty and good ratings on your Development Yelp? By intelligently executing a project that everyone relies upon day to day, that has impact, and legitimate sustainability (meaning the NGO jobs “should†be phased out eventually)? Or by winning a popularity contest by fitting the expectations for other perks? It’s a lot easier to do the latter. The incentives and potential rewards for supporting a claim that an NGO is doing great work are very high. Saying something negative can get you in trouble. We’re talking about tight-knit communities here. Why spend time giving critical feedback when it’s potentially going to get you in trouble?

3) In fact, why spend time giving feedback at all? Time and energy are very precious resources when you live in a place where parents are forced to leave small children to play unsupervised all day because they need to work and can’t pay for daycare. You’ll need to distribute some appreciation to get participation, unless participants are using a system for rating large-donor projects they’ve been beneficiaries of (see Danish Refugee Council example below), in which case much of the feedback might be in the form of calling out the continuing need for more assistance.

4) Many might respond that anonymizing this information will solve some of the problems I’ve mentioned. That’s essentially the route that Global Giving went with most of the stories on its Storytelling platform. But in that case, you don’t have very detailed knowledge about specific interventions or programs, which to me is the ultimate goal. Also, in most instances, asking for anonymous information from people is perhaps the purest yet least effective method of crowdsourcing. Anonymous inputs means you cannot hold people accountable for false information, and also removes a key incentive – to have an online presence and visibility. Even with Yelp, that’s clearly a motivator – a little bit of egotism.

So how do you make visible the inherent knowledge in a community of what works and what doesn’t? Certainly every Kibera resident has a lot of valuable knowledge, that, for instance, the vaunted bio-toilet is just stinking up the corner and no one’s using its supposed cooking gas. There is indeed a desire in Kibera, at least, to weed out the unproductive and even fake “briefcase†or “ghost†organizations that are supposed to reside there, but which aren’t in evidence on the ground, which means there is some latent incentive to provide data.

That’s why we hope our teams on the ground at Map Kibera and others like them will become the trusted informational resource for the community and will do a kind of due diligence on the local organizations and projects. In fact, this is a standard role that journalists play in a community – accountability and investigation. New kinds of citizen journalists and information centers can fill this role in places where there is limited news coverage. These informants aren’t anonymous at all – but they are protected by association with a network and local reputation.

In fact, an idea the Map Kibera team had was to create a directory of organizations and projects in the area where each group could have a page explaining what they do. The neutral nature of this project would invite in organizations in order to allow people to know who’s doing what where, and basic transparency would be built in. It would also help those tiny initiatives of regular community members – the orphanages, day cares, and youth groups – without much money or tech savvy to have some visibility and essentially prove their value. Mikel and I worked on this a little bit in a different format with Grassroots Jerusalem at www.grassrootsalquds.net. We are still seeking funding to finish this platform and establish it in Nairobi. Once that’s done, I think we can rely on our dedicated team to fact-check reports and post about various initiatives, and because they’re trusted members of the community, they can retrieve detailed opinions of citizens, both positive and negative and quote them on the site.

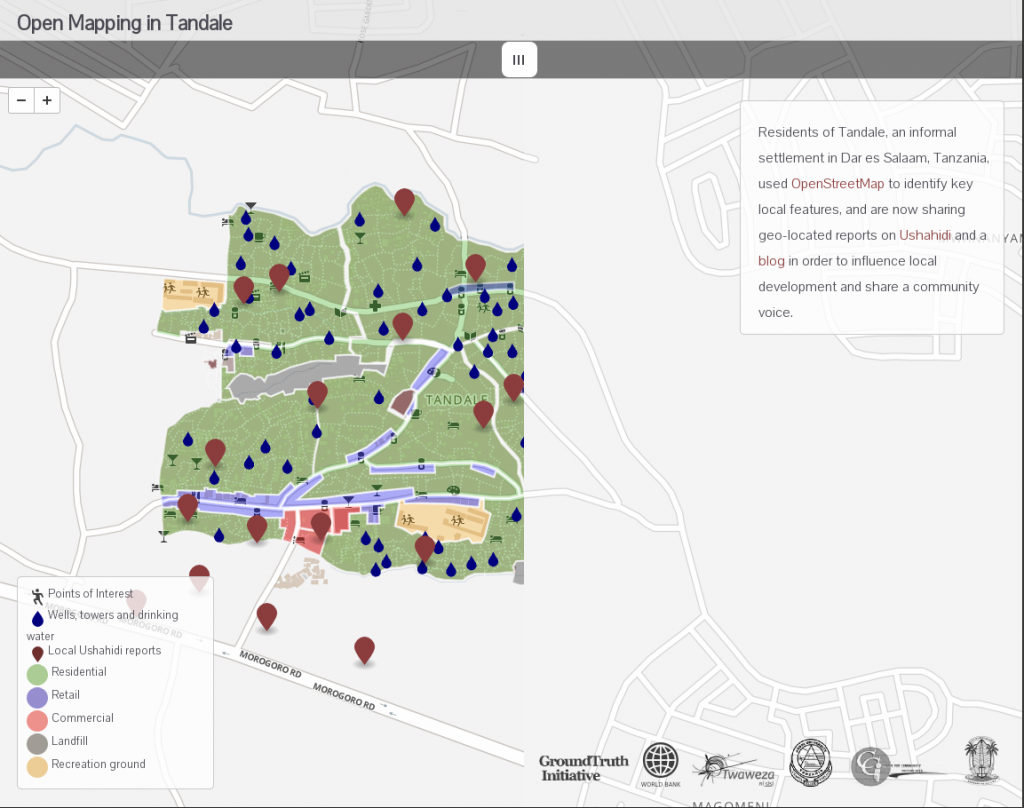

There is another way this could all work, which is to create a loop about government and large donor projects (those less likely to have a presence in the community) or simply highlight needs that require attention locally. This is more akin to the FixMyStreet concept, calling out local issues which have no project yet attached in hopes of triggering government or other support. We’ve tried to do this in Tandale, a slum in Dar es Salaam. There, we trained a team of reporters who’ve mapped the area and now post blog reports about conditions in the slum. See http://tandale.ramanitanzania.org/blog/. In this case, the loop has so far failed to close on the government or other responder’s side, in spite of initial promise. Here is where an influential third party can play an important role, such as the World Bank or UN.

I also found interesting this example of the Danish Refugee Council trying to solicit feedback on its work, which might not be a model to copy but gives a pretty accurate picture of what types of complaints a system might field. This is what a loop would often amount to: “We are requesting for power to charge our mobile phones, in order to reduce the challenges about the power and sent more SMS feedback.†Response: “According to your prioritization, DRC doesn’t provide electricity to any community.†Basically, that’s a no. I’m not sure that gets us much further, yet, than fielding such requests for more assistance. But, it does make public a normally very private exchange between donors and beneficiaries, when they are in that traditional relationship common to development schemes. I think this is a step in the right direction, because the more we open up these processes the more likely they will be open for questioning and productive critique.

The fact is that every “complaint†about “service delivery†is actually a citizen claiming a right – clean water, for instance – often in a place where there is no easy solution and there is a systemic and ultimately, political reason why neither NGOs nor government have yet to provide for such needs. Usually, that reason has little to do with the government (or big NGO/World Bank/UN etc) not knowing that the problem exists, sometimes in great detail.

The more that trustworthy community information representatives can detail and report and map and publicize and pressure and comment – and, do real journalism about – about the particular issue, the more likely that some downward accountability will be injected into the system. It’s also more likely that community members will begin to understand the forces at work in their neighborhoods and analyze what’s happening around them. It’s hard to imagine an information asymmetry as critical to address as that between residents of poor communities and major players in the development and government arenas, the 6 foot view vs the 30,000 foot.

Slick Visualization of Mapping Tandale

Posted: August 14th, 2012 | Author: mikel | Filed under: tandale, tech | 1 Comment »When the community of Tandale mapped itself in OpenStreetMap, they opened their community’s data to the creativity of the entire web. This visualization from our friends at Development Seed shows the dramatic before and after mapping in Tandale, with bright cartography and integrated Ushahidi reports. Hope this sparks more ideas for Tandale and other communities around the globe just now adding their voice to the web. Maya posted the details on how they put the map together.

Check it out at explore.ramanitanzania.org.

Moabi and Big Important Challenges for the GeoWeb

Posted: April 23rd, 2012 | Author: mikel | Filed under: Moabi, tech | 2 Comments »Recently finished a technical review of WWF’s Moabi platform, their geodata sharing platform to track deforestation, and came out with some important technical challenges for the GeoWeb I want to share with the mapping nerds.

Post continues on Brain Off