More Riotous Open Data Possibilities of Kerala

Posted: February 4th, 2013 | Author: mikel | Filed under: India | 1 Comment »Theyyam is a religious ceremony of Kerala (from Nila northwards, not in Chalakudy) performed annually and uniquely in hundreds, maybe thousands of temples (see note from Prakash in the comments clarifying..). A kind of possession takes place, the deity inhabits the performer of the Theyyam, through dancing, procession, drumming, fire, psychotropic altered states, elaborate costumes, sometimes sacrifice, all eventually bringing direct blessings, fortune telling, and satisfaction to the place and people in attendance. Superficially, there are similarities in style to other arts of Kerala, like the more refined and somewhat better known art of Kathakali, as well as Mudiyett, recognized by UNESCO as a more ancient source folk practice. We visited the master of Mudiyett, watched his evening instruction of local kids in drumming, and while fascinating, it’s hard in that brief exposure to understand how all these folk art forms fit together and relate to each other. So that’s just one place where I see open platforms for responsible tourism deepening visitors’ experiences by having communities themselves document and share knowledge and draw connections and tell the stories.

Kaleidoscopic Catholic Church in Kerala

Kerala has 75 kinds of bananas, and 75 lakh variations of culture. While we were in Chalakudy, an annual pilgrimage season to a local diety was starting, an intense Hindu bachelor God, which inspired a “temporary temple” in Chalakudy itself (no, I asked, it’s not burned like the Temple at Burning Man). People of different faiths are welcome to celebrate each others festivals, and whether Christian, Hindu or Muslim, the folk festivals all have a similar Kerala feel. There’s blending and borrowing: baroque cake-like churches lit up in kaleidoscopic fun fair lights (again fitting in right on the Playa); the oldest mosque in India nearby in Kodungallur has a Hindu-like oil lamp in the most inner place of worship. Theyyam sometimes involves very pre-Brahmin seeming animal sacrifice, and tribal peoples perform snake possession ceremonies. I can only wonder what kind of festivals were held at the oldest Synagogue “site” in India, since that community has all left for Israel (based on a gravestone marked 1264, though the entire community traces back at least til 3rd century AD).

Malayalam Calendar. Open Thayam could be just one simple hack of Open Watersheds.

Prakash is a passionate, obsessive collector of Kerala culture. He diligently seeks out the locations of athaani rest blocks, marking the ancient trade routes. He’s called on frequently as an expert on Thayam, having collected the location and timing of hundreds of ceremonies. And he’s generous with his knowledge. From what is his private word doc, we could potentially iterate and create a simple site openly sharing the location, timing and details of Thayam. Start just with a single site, Leaflet or OpenLayers with a timeline, sharing this data. Iterate to something db-backed to help Prakash and others manage the collection and update the collection into the thousands (complexly, timings vary slightly each year because of the subtly different Malayalam calendar). From culture, to passion, to data, to openness, to open culture.

The Temple 2010 on Burning Man Earth

The vibrancy, the pervasive creative and sacredness of Kerala, where any group of trees can become a sacred grove, reminds me of Burning Man, and I realize the platform for creating, sharing and connecting of Kerala’s river basins could look a bit like the structure of Burning Man Earth: there are camps (or places in Kerala context), art, events, and people; and means to connect, communicate, share media, and pivot around all these. One idea that bounced around BME were tools to create your own schedule (pre-selection) and record your own experience (via automatically linking GPS traces to places and art and events). The work of Blue Yonder for tourists is based in part around developing itineraries, and I could eventually see itinerary functions directly in that responsible tourism platform. Before our arrival to Chalakudy we received an ambitious itinerary (exhaustively including every identified responsible tourism site) and having a map and idea of how much road travel the days would entail would have helped us prepare as tourists and sealed the memories. Of course, we were there to actually help create that map…

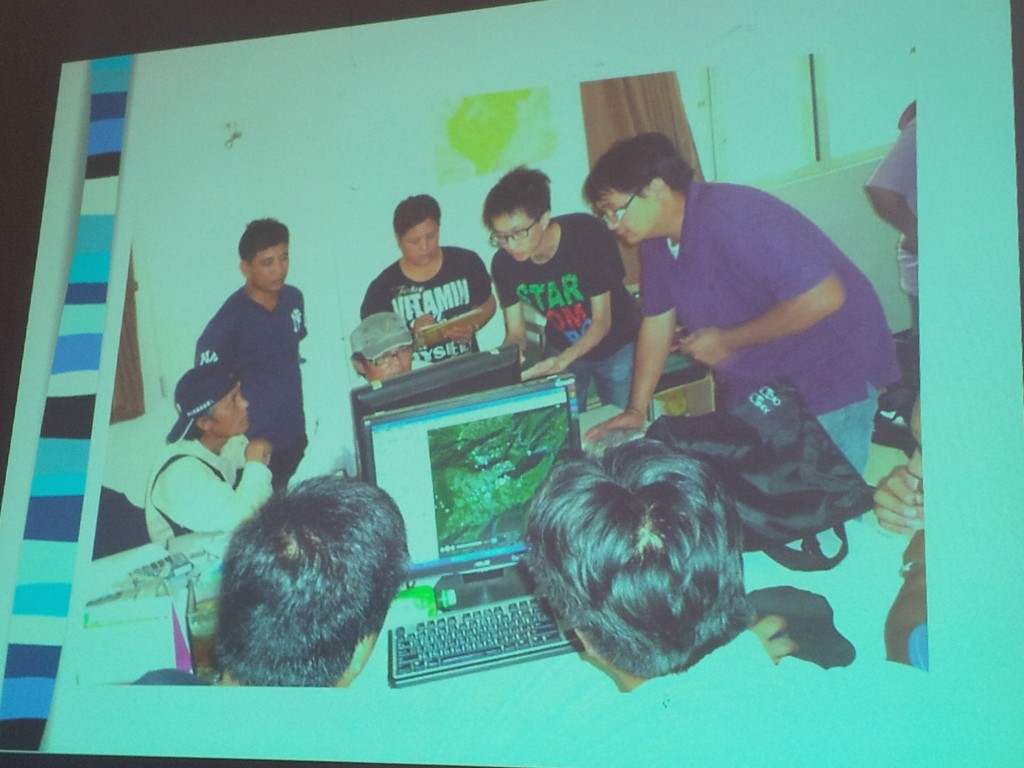

Participatory Mapping of Indigenous Names in Taiwan

Open Watershed Data, and a methodology of responsible tourism for river basins, provides a context for these media tools to develop. Design workshops, data fellowships, (even, um, yes, maybe) hackathons, could enable technical and design participation in creating amazing tools for cultures, communities, environments. Kerala has a volunteer spirit, and people want to contribute to “the something greater” when they have the chance. Folks described as “literary people” research local place names, recording the stories and meanings embedded in those names. While in Taiwan, I sat in on a session with an elder of an indigenous group, while he browsed his village in Google Earth, he told stories of (and a dozen students dutifully recorded) the names of every place, indicating deep knowledge of the landscape, how to practice agriculture, what to expect from the weather, commerating the efforts of the past. Indigenous people of Taiwan have gained stature in their society, and they are working to see through the right to return to indigenous names in their communities, yet the big challenges of responding to change remain, including increasing interest from Han Chinese tourists. The struggle is to maintain the integrity of the culture, preserve the culture, as money comes in, avoiding division and degeneration as more opportunities open up. One tribe managed to organize into a tourist cooperative, so home stays and the like don’t compete but cooperate. Many issues are over the land itself. Do individuals in the tribe have the right to sell land to outsiders for agriculture, even if risking overuse and environmental degredation, as it is their land, or is there a collective responsibility in the notion of tribal rights?

The issues of land rights management, cultural preservation all ring true to Kerala, with overlapping jurisdiction of tribal reserves, forest reserves, water bodies, and individual rights. In Kerala, what to say when the people of the river in some desperation, mine the sand in order to make a little money and survive, yet hasten further destruction of the river they depend on. The last remaining sand bank of Chalakudy was saved due to collective effort, as it was adjacent to a religious site. Hence, culture and value are the greatest strengths to seeing long term benefit vs short term individual gain. Perhaps sharing openly, and inviting the real interest of the wider world, can change the trajectory of damanged rivers and lost ways of life.

There is a tremendous wealth in Chalakudy. The crop of this very place, pepper, drove globalization mellenia ago. Roman coins have been found here. Jewish and Christian communities have been here since the 3 century AD. The first mosque and first synagogue in India are here. Colombus was looking for Chalakudy. The Portugeuse built the first European fort on this river. All of this is smartly being invested in by the Kerala government in the Muziris Heritage project. It’s wonderful, and likely to draw many tourists, both international and from India’s growing middle class (the India tourist riotous take of a place like the Athirappalli Waterfall is an experience in itself). But what of the every day history still there today. There are growing numbers of people who want to know more, surely typical and niche, but a crucial part of the tourism “industry”, or maybe better, “culture”. During our last trip to Nila, we impromptly stopped at a matchstick factory. The ruckus of this very basic mechanical operation was transfixing, totally normal to the people working there, who couldn’t understand our interest … but have you ever seen matchsticks made by hand? Social media and the internet are connecting unprecedently, changing relentlessly, challenging (I heard young Kerala guys listening to Gangam Style on their phones). We’re in that moment where perhaps this force of technology can discover and perserve the extraordinary normal of Kerala.

from Prakash…

Regarding Theyyam (also known as Thira)… The complete form of this ritual is seen in Kannur, Kasaragod and part of Kozhikode District. In other parts of Kozhikode district similar or same ritual art form is performed and is generally called Thira, with some differences in costume, style of presentation etc. In all these places Theyyam/Thira is God or Goddess itself..

Further down, near the bank of River Nila, there is another folkform called Thira ( may be derived from the same concept), here these characters are act as the subordinates/militants of Goddess.