What is the Logical Conclusion for Feedback Systems?

Posted: November 6th, 2014 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback | Tags: Feedback Labs, M&E, Open Schools Kenya | Leave a comment »I’ll confess, I’ve never been a huge fan of M&E. While I absolutely love the data and statistics and numbers and fascinating insights of a good evaluation, as the founder of a nonprofit in Kenya, Map Kibera, doing a quality job on monitoring and much less evaluation was daunting.

Not only because we were under-resourced, and lacked high staff capacity (our members all coming from the Kibera slum) – but Map Kibera was actually set up in part to counter a problem obvious to any Kibera resident. NGOs and researchers were constantly collecting data, but then were usually never seen or heard from again.

Where Does the Data Go?

Was that data even seen again by the collecting organization after their project reports were turned in? What good was all that time and energy spent – on the part of the organization, but more importantly on the part of the good citizens of Kibera, who were tired of answering questions about their income and toilet habits three times in one week? And didn’t they have a right to access the resulting information as well?

Now many organizations, including Map Kibera, our organization GroundTruth Initiative, and others such as the panelists who joined me at the M&E Tech Feedback Loops Plenary: Labor Link, Global Giving, and even the World Bank have put an emphasis on citizen feedback as the core of a new way of doing development.

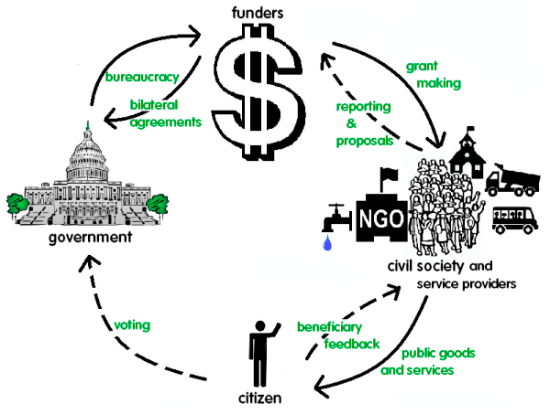

It’s possible to imagine a world where some of the main reasons for doing monitoring and evaluation are shifted over to citizens themselves – because they want to hold to account both governmental and non-governmental organizations so that the services not only get to the right people, but those people can drive the agenda for what’s needed where.

While a complicated study on, say, the school system and education needs of Kibera people might provide insight, if it sits on a shelf and doesn’t inspire grassroots pressure to shift priorities and improve education, what is the use of it? Why not instead invest in efforts to collect open data on education jointly with citizens, like our Open Schools Kenya initiative?

The benefit here is that the information is open and collectively tended – meaning kept up to date, shared, made comparable with other data sets (like Kenya’s Open Data releases from the government), and used for more than just one isolated study. It’s a way for the community to assess the status of local education itself. In our own neighborhoods and school systems, we wouldn’t have it any other way.

A Citizen Led Future

As noted by Britt Lake of Global Giving on our panel discussion, taking this concept to its logical conclusion there would be a loss of control by development agencies. Is this the real hurdle to citizen-led data collection? To what extent can aid systems be devolved to the people who are meant to primarily benefit?

A truly forward-thinking organization would embrace this shift, because with better information being collected and used at the grassroots, there will be more aid transparency overall and less opportunity for gaming the system. If you think that no small CBO has ever submitted a bogus progress report which went up the chain at USAID, think again.

Nowhere in this system is there incentive to give an accurate account of failures or document intelligent but unpredicted programmatic adaptations and detours that were made. Yet if there’s one thing I know the Kibera people want, it’s for the many organizations they see around them in the slum to be held accountable for all the funds they receive, and for delivering on their years of promises for improving the slum.

In fact, transparency around aid at this hyperlocal level is something we should even feel an ethical obligation to provide. Here’s hoping that in 20 years, the impact of the open data and feedback movements will mean that public information about projects done in the public good is reflexively open and responsive, and M&E as a separate and often neglected discipline is a thing of the past.

This post was originally featured on ICT Works as a Guest Post.

Making Education Information Available to All in Kibera

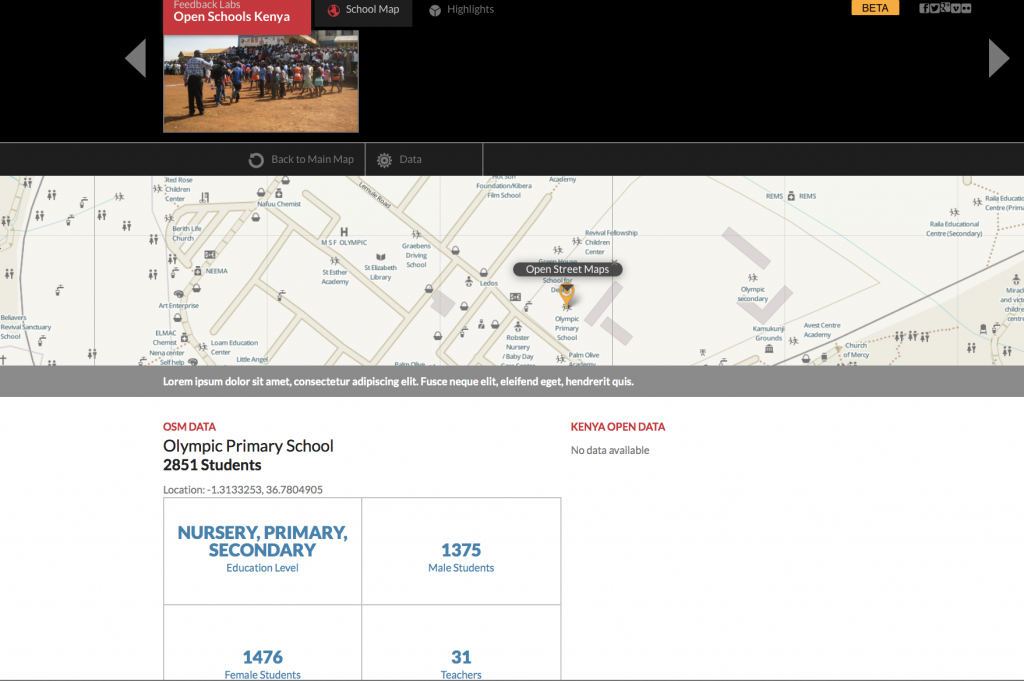

Posted: July 9th, 2014 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, kenya, openstreetmap | Tags: education, Feedback Labs, Gates Foundation | 1 Comment »How can all the information about Kenyan schools, including data released by the Kenyan government, and citizen mapping, have a greater impact on education? We’ve been working for the past few months on a project to make information about schools much more available and useful in Kenya. It’s a joint operation between GroundTruth Initiative, Map Kibera, Development Gateway, Feedback Labs, and the Gates Foundation among others.

Many people collect information about education – and they sometimes make it open and free to use. So, why isn’t it easy to find information about a particular school – for a parent, or for an education researcher? Much of the information that’s out there isn’t connected to the other data – and especially when it comes to informal schools, which provide a great deal of the education services in places like informal settlements.

Citizen data – like mapping schools using OpenStreetMap – should also be easy to combine and compare with official education data. And finally, all this info could be accessible and useful to everyone from parents to policymakers.

So, we’ve started with Kibera as a test location for the Open Schools Kenya project.

Over the past few months, the Map Kibera team has engaged parents, school leaders, and education officials in Kibera to find out how the informal school sector can be more visible, and to assess the demand for information on education. Now, a widespread effort is underway by Map Kibera to make sure that the schools data that the team collected a few years ago is still accurate, and to add new info as well. We’re also collecting photos of each school, no matter how small. Every one will have a page on the website, really bringing the informal school sector to light. Formal schools in Kibera will be there too.

Much of the work so far has been around engaging important leaders in the community, who care about local kids getting the best education. Mikel Maron of GroundTruth was recently in Nairobi working on the project and will be updating in a separate post about this busy trip. Ultimately, the community wants to know more about its schools, and to improve them. So do education supporters throughout Kenya.

But beyond this important mission of organizing and making interoperable many data sets across the vast education sector in Kenya, we’re also working on an ambitious hypothesis: that parents and community leaders in education will want to provide feedback on schools, which in turn will inform policy and improve individual schools. Ultimately, our platform will be a place where people can not only be consumers of information, but will provide their own opinions and suggestions on schools, and, importantly, submit corrections and updates to the data on the site. Given the early positive response to these ideas, we’re optimistic that this will be possible in Kibera and also Kenya-wide.

The project is not just about education, either. It has far-reaching potential in other sectors as well. We hope to demonstrate that citizen data, official data, academic research and more can come together and be part of a conversation with those on the ground who feel the impact most of government policy in every sector – ordinary citizens. And, that this kind of conversation means that people “own†their own information, and we can see the beginnings of a true “feedback loop†or dialogue between citizens and government, through the medium of shared data.

This article was originally posted on the Map Kibera blog, July 3, 2014.