How to Improve Innovation Funding: lessons from the MakeSense project

Posted: June 17th, 2016 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, Funding, Sensors | Leave a comment »

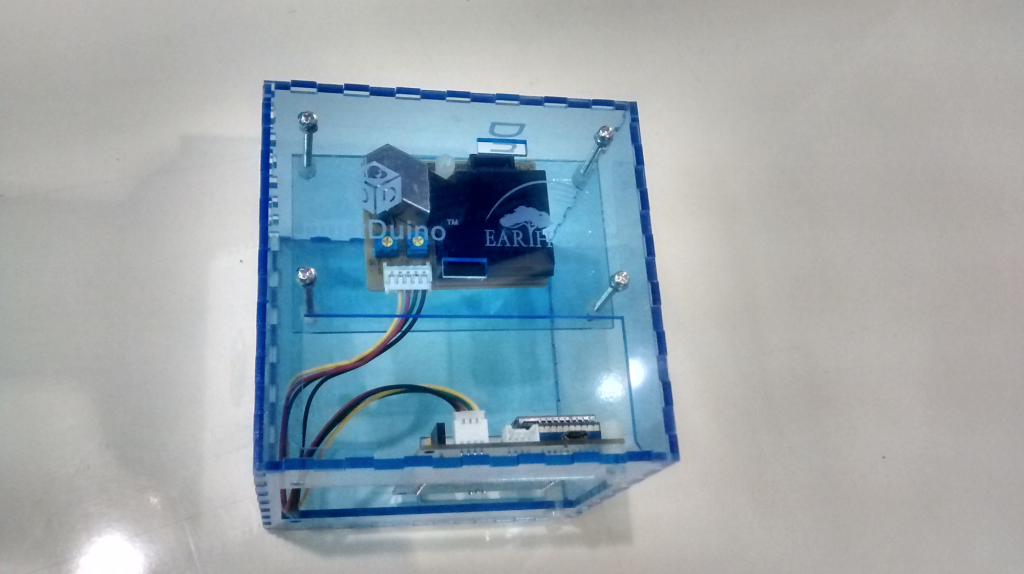

MakeSense was meant to test feedback loops from “citizen-led sensor monitoring of environmental factors†in the Brazilian Amazon, providing structured, accurate and reliable data to compare against government measurements and news stories in the Amazon basin. The project centered around developing, manufacturing and field testing DustDuino sensors already prototyped by Internews, and developing a dedicated site to display the results at OpenDustMap.

It may seem obvious that it was too ambitious to try to create a mass-produced hardware prototype with two types of connectivity, a documenting website, do actual community engagement and testing (in the Amazon) AND do further business development, all for $60,000, not to mention the coordination required. But, it is also true that typical funds available for innovation lend themselves to this kind of overreach.

Good practice would be to support innovators throughout the process, including (reasonable) investment in team process (while still requiring real-life testing and results), and opportunities for further fundraising based on “lessons†and redesign from a first phase. As well, an expectation that the team be reconfigured, perhaps losing some members and gaining others between stages, plus defining a clear leadership process.

Supportive and intensive incubation, with honest assessment built in through funding for evaluations such as the one we published for this project would go a long way toward better innovation results.

Funders should also require transparency and honest evaluation throughout. If a sponsored project or product cannot find any problems or obstacles to share about publicly, they’re simply not being honest. Funders could go a long way toward making this kind of transparency the norm instead of the exception. In spite of an apparent “Fail Fairâ€-influenced acculturation toward embracing failure and learning, the vast majority of projects still do not subject themselves to any public discussion that goes beyond salesmanship. This is often in fear of causing donors to abandon the project. Instead, donors could find ways to reward such honest self-evaluation and agile redirection.

Learning from the MakeSense DustDuino Air Quality Sensor Pilot in Brazil

Posted: May 5th, 2016 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback, Sensors, tech | Tags: DustDuino, MakeSense | Leave a comment »Introducing new technology in international development is hard. And all too often, the key details of what actually happened in a project are hidden — especially when the project doesn’t quite go as planned. As part of the MakeSense project team, we are practicing transparency by sharing all the twists, turns and lessons of our work. We hope it is useful for others working with sensors and other technology, and inspires greater transparency overall in development practice.

Please have a look at GroundTruth’s complete narrative history of the MakeSense pilot here on Medium, or download a PDF of the full report here.Â

The MakeSense project was supported by Feedback Labs and the project team included GroundTruth, Internews, InfoAmazonia, Frontline SMS/ SIMLab, and Development Seed. MakeSense was meant to test feedback loops from “citizen-led sensor monitoring of environmental factors” in the Brazilian Amazon, providing structured, accurate and reliable data to compare against government measurements and news stories in the Amazon basin. Over the course of the project, DustDuino air quality sensor devices were manufactured and sent to Brazil. However, the team made several detours from the initial plan, and ultimately we were not able to fulfill our ambitious goals. We did succeed in drawing some important learnings from the work.

Lessons Learned:

Technical Challenges

- Technical Difficulties are to be expected

Setting up a new hardware is not like setting up software: when something goes wrong, the entire device may have to go back to the drawing board. Delays are common and costly. This should be expected and understood, and even built into the project design, with adequate developer time to work out bugs in the software as well as hardware. At the same time, software problems also require attention and resources to work out which became an issue for this project as well, which often relied upon volunteer backup technical assistance.

- Simplify Technical Know-how Required for Your Device

The project demonstrated that it is important to aim for the everyday potential user as soon as possible. The prototype, while mass-produced, still required assembly and a slight learning curve for those not familiar with its components, and also needed some systems maintenance in each location. Internews plans for the DustDuino’s next stage to be more “Plug-and-playâ€â€Šâ€” most people don’t have the ability to build or troubleshoot a device themselves.

- Consider Data Systems in Depth

This project suffered from a less well-thought-out data and pipeline system, which required much more investment than initially considered. For instance, the sensor was intended to send signals over either Wi-Fi or GSM, but the required code for the device itself, and the destination of the data shifted throughout the project. Having a working data pipeline and display online consumed a great deal of project budget and ultimately stalled.

- Prioritize Data Quality

The production of reliable data, and scientifically valid data, also needs to be well planned for. This pilot showed how challenging it can be to get enough data, and to correct issues in hardware that may interfere with readings. Without this very strong data, it is nearly impossible to successfully promote the prototype, much less provide journalists and the general public with a tool for accountability.

Implementation

It is important to be intentional about technical vs programmatic allocation, and not underestimate the need for implementation funding. It is often the case that software and hardware development use up the majority of a grant budget, while programmatic and implementation or field-based design “with†processes get short shrift in the inception phase. Decision making about whether to front-load the technology development or to develop quick but rough in order to get prototypes to the field quickly, as referenced in the narrative, should be made intentionally and consciously. Non-technical partners or team members should be aware of the incentives present for technical team members to emphasize hardware/software development over often equally critical local engagement and field testing processes, and ideally have an understanding of the basic technical project requirements and operations. This project suffered from different understandings of this prioritization and timeline.

Funding Paralysis

The anticipation of a need for future funding dominated early conversations, highlighting a typical bind: funding available tends to skew to piloting with no follow-up opportunities for successful pilots. This means that before the pilot even produces its results, organizations must begin to source other funds. So, they must allocate time to business development as well, which can be difficult if not impossible, and face pressure to create marketing materials and other public relations pieces. This can also in some cases (although not with this pilot) lead to very premature claims of success and a lack of transparency. During this project, there was some disagreement among team members about how much to use this pilot fund to support the search for further investment — almost as a proposal development fund — and how much to spend on the actual proof of concept through hardware/software development and field testing.

This is a lesson for donors especially: when looking for innovative and experimental work, include opportunities for scale-up and growth funding or have a plan in mind for supporting your most successful pilots.

Teamwork

A consortium project is never easy. A great deal of time is required simply to bring everyone to the same basic understanding of the project. This time should be adequately budgeted for from the start. Managing such a team is a challenge, and experienced and very highly organized leadership helps the process. FrontlineSMS (which received and managed the funding from Feedback Labs) specifically indicated they did not sufficiently anticipate this extensive requirement. Also, implementing a flat structure to decision making was a huge challenge for this team. Though it was in the collective interest to achieve major goals, like follow-on funding, community engagement, and a working prototype, there were no resources devoted to coordinating the consortium nor any special authority to make decisions, sometimes leading to members operating at cross purposes. Consistent leadership was lacking, while decision-making and operational coordination were very hard given quite divergent expectations for the project and kinds of skills and experience. This is not to say that consortium projects are a poor model or teams should not use a flat structure, but that leading or guiding such a team is a specialty role which should be well considered and resourced.

Part of the challenge in this case was that the lead grantee role in the consortium actually shifted in 2015 from FrontlineSMS to SIMLab, its parent company, when the FrontlineSMS team were spun out with their software at the end of 2014. The consortium members were largely autonomous, without regular meetings and coordination until July 2015, when SIMLab instituted monthly meetings and more consistent use of Basecamp.

Communications

Set up clear communications frameworks in advance, including bug reporting mechanisms as well as correction responsibilities. Delays in reporting bugs with Development Seed and FrontlineSMS APIs contributed significantly to the instability of the sensors in the field. Strong information flow about problems, and speedy remote decision-making, was never really achieved. At the same time, efficiency in such consortia is paramount, so that time isn’t taken from operational matters with coordination meetings — so a balance must be struck. This project eventually successfully incorporated the use of BaseCamp.

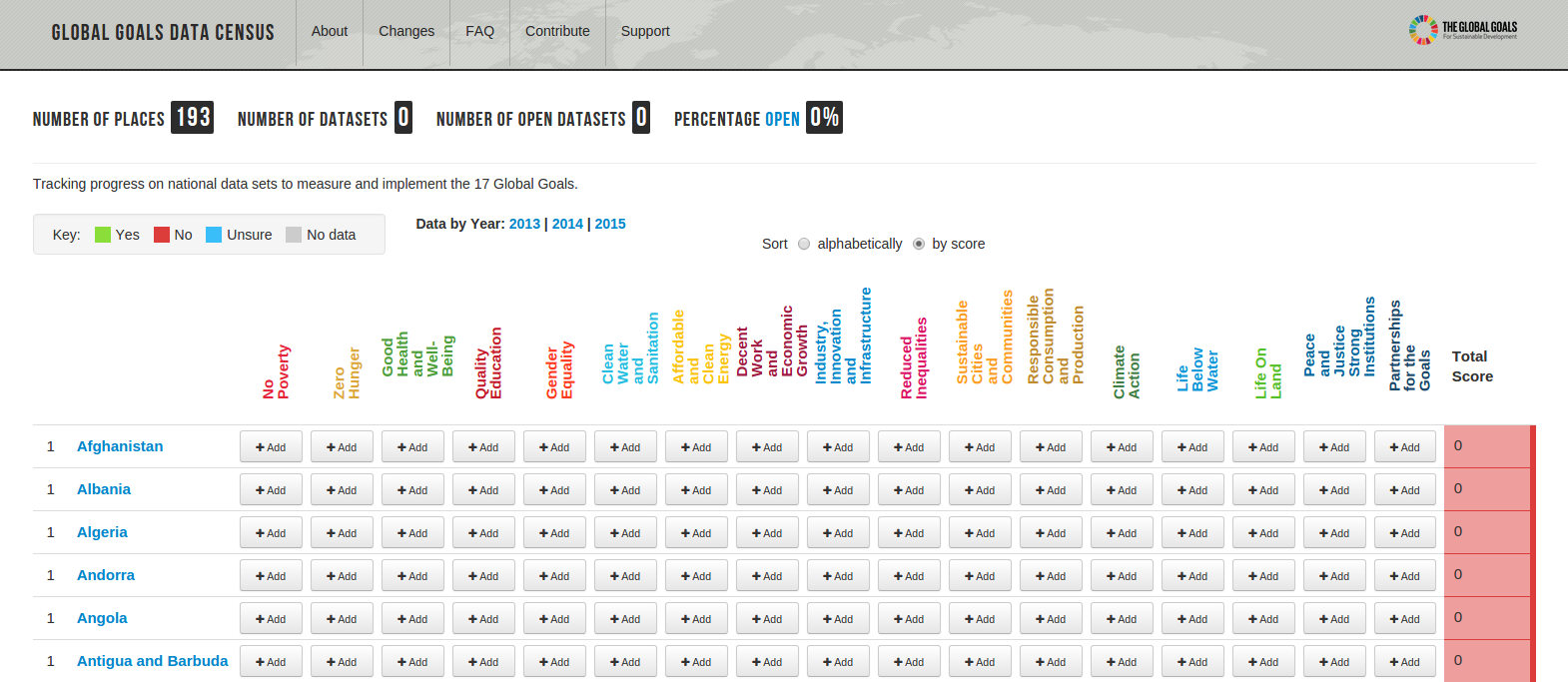

Let’s Build the Global Goals Data Census

Posted: October 5th, 2015 | Author: mikel | Filed under: global-goals | 1 Comment »The Global Goals have launched and data is a big part of the conversation. And now, we want to act … create and use data to measure and meet the goals. I’m presenting here a “sketch” of a way to track what data we have, what we can do with it, and what’s missing. It’s a Global Goals Data Census, a bit of working, forked code to iterate and advance, and raise a bunch of practical questions.

image by @jcrowley

The Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data launched last week, to address the crisis of poor data to address the Goals. Included were U.S. Government commitments to ” Innovating with open geographic data”. In the run up, events contributed to building practical momentum, like Africa Open Data Conference, Con Datos, and especially the SDG Community Data Event here in DC, facilitated by the epic Allen Gunn. And the Solutions Summit gathered a huge number of ideas, many of which touch on data.

Among many interesting topics, the SDG Community Data Event developed many ideas and commitments, including

- Put all the data in one place

- Create an inventory of indicators: + What exists ; + What goals are they relevant for

- Build a global goals dashboard

The action of taking stock of what data we have, and what we need, looks like a perfect place to start.

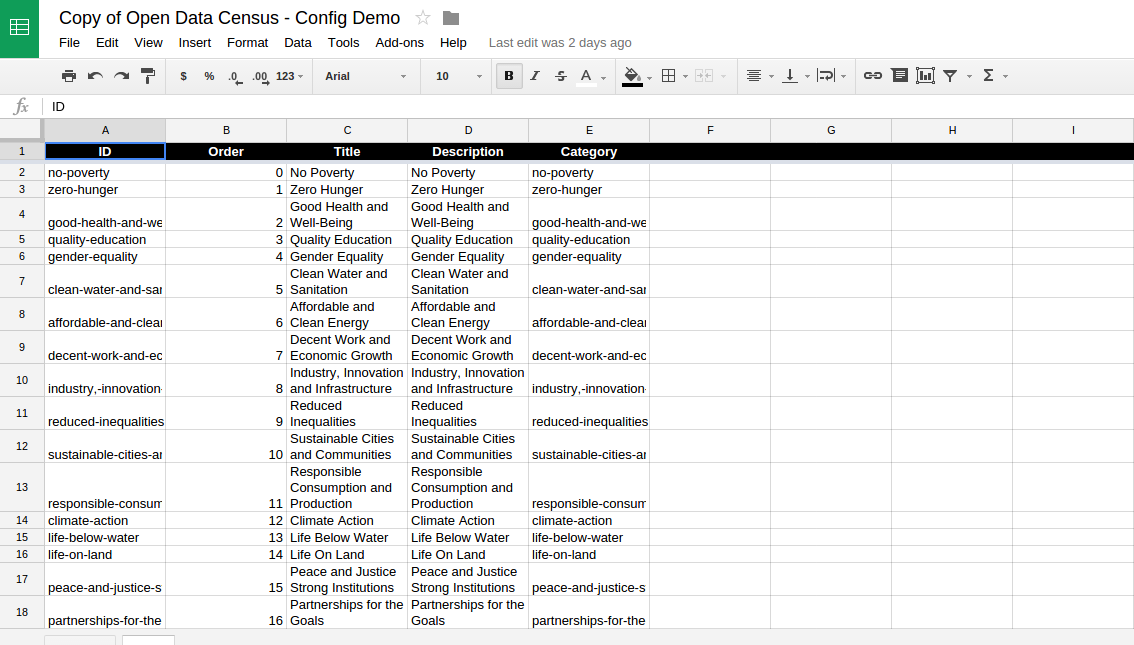

OKFN’s Open Data Census is a service/software/methodology for tracking the status of open data locally/regionally/globally. I forked the opendatacensus, got it running on our dev server, made a few presentation tweaks, and configured (all configuration is done via a Google Spreadsheet).

Each row of the Global Goals Data Census is a country, and each column is one of the 17 Goals. Each Goal links to a section of the SDGs Data, built off a machine readable listing of all the goals, targets and indicators.

This is truly a strawman, a quick iteration to get development going. It should work, so give it a quick test to help formulate thoughts for what’s next.

This exercise brought up a bunch of ideas and questions for me. Would love to discuss this with you.

- Does it make sense to track per Indicator, in addition to the overall Goal? There been a lot of work on Indicators, and they will be officially chosen next year.

- There may be multiple available Datasets per Goal of Indicator. The OpenDataCensus assumes only one Dataset per cell.

- For the Global Goals, are there non-open Datasets we should consider, due to legitimate reasons (like privacy).

- Besides tracking Datasets, we want to track the producers, users and associated organizations. The OpenDataCensus assume data is coming from one place (the responsible government entity). Much more complex landscape for the Goals.

- What is the overlap with the Global Open Data Index? Certainly the Goals overlap a little with the Datasets in the Global Census, but not completely. And the Index doesn’t cover every country that has signed up for the Goals. Something to definitely discuss more.

- Undertaking the Census, filling the cells, is the actual hard work. Who is motivated to take part, and how best to leverage related efforts.

- Many relevant data sets are global or regional in scope. How best to incorporate in a nationally focused census? How to fit in datasets like OpenStreetMap which are relevant to many Goals?

- There is an excellent line of discussion on sub-national data. There are also non-national entities which may want to track Goals separately. How to incorporate?

- What other kinds of questions do we want to ask about the Datasets, beyond how Open they are? Should we track things like the kind of data (geo, etc), the quality, the methodology, etc?

- Where could the Global Goals Data Census live? A good use of http://data.org/?

@webfoundation on open data and the SDGs

Does this interest you? Let’s find each other and keep going. Comment here, or file issues. One good upcoming opportunity is the Open Government Partnership Summit … will be a great time to focus and iterate on the Global Goals Data Census. There will be an effort to expand adoption of the Open Data Charter, “recognizing that to achieve the Global Goals, open data must be accessible, comparable and timely for anyone to reuse, anywhere and anytime”. I’ll be there with lots of mapping friends and ready to hack.

OSM: Mapping Power to the People?

Posted: June 5th, 2015 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: OSM, tech | Tags: Community, data, future of OSM, power | 2 Comments »As you probably know, OpenStreetMap is a global project to create a shared map of the whole world. A user-created map, that is. Of course, in a project where anyone can add their data, there are many forms this can take, but the fundamental idea allows for local ownership of local maps — a power shift from the historical mapping process. Now, if I want to add that new cafe in my neighborhood to the OSM map, I can do it, and quickly. And I don’t have to worry that I’m giving away my data to a corporate behemoth like Google — open and free means no owner.

But lately I’ve noticed a trend away from the radical potential of such hyperlocal data ownership, as OSM gets more widely used and recognized, inspiring everyone from the White House to the Guardian to get involved in remote mapping (using satellite imagery to trace map details onto OSM, like roads and building outlines). But remote activities still require people who know the area being mapped to add the crucial details, like names of roads and types of buildings. So why is the trend worrying?

Since first training 13 young people in the Kibera slum to map their own community using OSM, in 2009, I have focused quite a bit on questions of the local — where things actually happen. And the global aid and development industry, as anyone can see who has worked very closely with people anywhere from urban slums to rural villages, tends to remain an activity that begins in Washington (or at best, say, Nairobi’s glassy office buildings) and ends where people actually live. Mapping, on the other hand, is an activity that is inherently the other way around — best and most accurately done by residents of a place. And, I would argue, mapping can therefore actually play a role in shifting this locus of decision making.

More poetically perhaps, I also see maps as representations of who made them rather than a place per se. So if the community maps itself, that’s what they see. And that can shift the planning process to highlight something different — local priorities. After all, a resident of a place knows things faster, and better, than any outsider, and new technology can in theory highlight and legitimize this local knowledge. But just as easily, it seems, it can expedite data extraction.

Even more importantly, as any social scientist will tell you, a resident of a place knows the relevant meaning and context of the “facts†that are collected — the story behind the data. An outsider often has no idea what they’re actually looking at, even if it seems apparent. (An illustrative anecdote: I was recently in Dhaka and we noticed a political poster with a tennis racket symbol. We wondered why use a tennis racket to represent this candidate? That’s not a tennis racket — it’s a racket-shaped electric mosquito zapper, said one Bangladeshi. What you think you see is not the reality that counts!)

So, when the process of mapping gets turned around — with outlines done first by remote tracing and locals left to “fill in the blanks†for those outside pre-determined agendas, that sense of prioritization is flipped. In spite of attempts to include local mappers, needs are often focused on the external (usually large multilateral) agency, leaving just a few skilled country residents to add names to features in places they’ve never set foot in before.

There are degrees of local that we are failing to account for. Thinking that once we’ve engaged anyone “local†(ie, non-foreign) in a mapping project we’ve already leveled the playing field is letting ourselves off the hook too easily. By painting the local with one brush we fail to engage people within their own neighborhood (not to mention linguistic, ethnic group or gender). We underestimate the power of negative stereotypes in every city and country against those in the direst straits, including pervasive ideas of lack of ability, tech or otherwise. This is especially problematic when dealing with the complex dynamics of urban slums, in my experience. But any place where we hope to eventually inspire a cadre of local citizen mappers who care about getting the (data) story right, it’s crucial to diversify.

Having dealt with these challenges nearly from day one of Map Kibera, I’m particularly sensitive to the question “How does a map help the people living in the place represented?†You might say that development agencies and governments have a clear aim for their maps that will help in very important ways. Therefore, a faster and more complete map from a technical standpoint is always better. (Indeed, getting support for open maps in the first place is quite an achievement). But more often than you’d think, the map seems to be made for its own sake or to have a quick showpiece.

Even if our answer is that the map would help if disaster struck, that seems to be missing the point and might not even be true in most cases. Strong local engagement and leadership are said to be “best practice†even in cases of disaster response and preparedness, though they aren’t yet the norm. Since the recent earthquake in Nepal, there has been a very successful mapping response thanks to local OSMers Kathmandu Living Labs. But critically, this group had been working hard locally for some time. And we should see this as a great starting point for widespread engagement, not an end product.

Another problem is that established mapping processes in the field aren’t questioned much, even when it comes to OSM. Since mapping is often something people do who are techies of some kind — GIS people, programmers, urban planners — organizers sometimes seem to forget to simplify to the lowest common denominator needed for a project. Does the project really need to use several types of technological tools and collect every building outline? Does every building address need to be mapped? If not, it just seems like an easy win — why not collect everything? One reason not to is because later when you find you need local buy-in, even OSM may be viewed as an outsider project meant to dominate a neighborhood, a city, especially in sensitive neighborhoods where this has indeed been a primary use of maps. I wonder if people will one day want to create “our map†separately from OSM. A different global map wiki which is geared toward self-determination, perhaps? That would be a major loss for the OSM community.

Perhaps I seem stuck on questions of “whose map†and “by whom, for whom?†Well, that’s what intrigued me about OSM in the first place. We used to talk a lot about the democratizing potential of the internet, about wikis and open source as a model for a new kind of non-hierarchical online organizing. Now, it’s clear that because of low capacity and low access, it’s actually pretty easy to bypass the poor, the offline, the unmapped. And because of higher capacity among wealthier professionals and students in national capitals globally, it’s easier for them to do the job of mapping their country instead. Of course there isn’t anything wrong with people coming together digitally over thousands of miles to create a map. In an idealistic sense it’s a beautiful thing.

But the fact is, we (that is, technologists and aid workers — both foreign and not) still tend to privilege our own knowledge and capacity far and away over that of the people we are seeking to help. We can send messages to the poor through a mobile phone, strategize on what poster to put up where, but the survey to figure out who lives there and what they care about? Still done by outsiders, hiring locals only as data extractors. As knowledge and expertise used to make decisions becomes more data-driven and complex, a class of expert and policy maker is created that is even more out of reach. Access has always been messy. Now (thanks in part to mobile phone proliferation and without much further analysis), we hardly talk about access anymore. The fad has shifted to “big data†and other tech uses at the very top.

To me, OSM was always so much more than just a place where people shared data. It was one small way to solve this problem of invisibility bestowed by poverty.

The possibilities of OSM to empower the least powerful are still tantalizingly close on the horizon. With just a few tweaks to existing thinking, I hope we can tip the scale — we can prioritize the truly local and allow the global to serve it. But to do so we must resist glib and lazy thinking around how those processes actually work. We must pay attention to order of operations (who maps first? whose data shows up as default?), and subtleties of ownership and buy-in, and we must examine who we think of as “localâ€.

But most of all, and most simply, we have to reorient our thinking in designing mapping projects. It could be quite straightforward, for instance:

- integrating more localized thinking into training courses and OSM materials, suggesting that people on the margins (such as slumdwellers) can and should be learning OSM tools as well;

- training people to think about social context and local priorities not just technology;

- doing more offline outreach and print map distribution; creating new map renderings highlighting levels of local and remote mapping;

- making it the norm that residents of a neighborhood be involved in early project planning;

- engaging with people who have long done offline forms of data gathering and mapping in their communities.

- Considering that first pass on a blank map might matter.

- And considering that leading local technical mappers start to conceptualize their roles more as mentors to communities and to new mappers in those places than as expert consultants to foreign organizations. I’ve seen the light bulb go on when that happens.

Yes, ultimately, we will do best to address the incentive structures of international funding which are keeping us from achieving what we’d all undoubtedly wish to see, which is everyone getting the opportunity to put themselves on the map.

Many will say that it is just too hard, too time consuming, too cumbersome, too expensive, too — something — to really prioritize local in the way I’m talking about. We’ll never hit “scale†for instance. Something needs to be done now. But I would ask you to reconsider. I believe that in fact, sensitive and thoughtful engagement with communities is the only real path to scale and sustainability for many kinds of “crowd-†or “citizen-†based data work that is now happening, and most certainly the only way to reach the real target of any development-oriented data effort — actual improvements in the lives of the world’s poor and marginalized.

This post also appears here on Medium.

What is the Logical Conclusion for Feedback Systems?

Posted: November 6th, 2014 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: citizen feedback | Tags: Feedback Labs, M&E, Open Schools Kenya | Leave a comment »I’ll confess, I’ve never been a huge fan of M&E. While I absolutely love the data and statistics and numbers and fascinating insights of a good evaluation, as the founder of a nonprofit in Kenya, Map Kibera, doing a quality job on monitoring and much less evaluation was daunting.

Not only because we were under-resourced, and lacked high staff capacity (our members all coming from the Kibera slum) – but Map Kibera was actually set up in part to counter a problem obvious to any Kibera resident. NGOs and researchers were constantly collecting data, but then were usually never seen or heard from again.

Where Does the Data Go?

Was that data even seen again by the collecting organization after their project reports were turned in? What good was all that time and energy spent – on the part of the organization, but more importantly on the part of the good citizens of Kibera, who were tired of answering questions about their income and toilet habits three times in one week? And didn’t they have a right to access the resulting information as well?

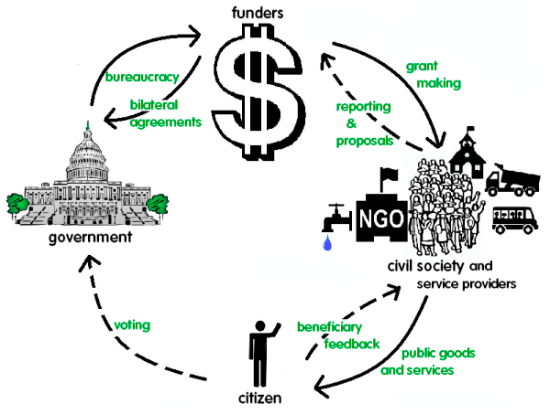

Now many organizations, including Map Kibera, our organization GroundTruth Initiative, and others such as the panelists who joined me at the M&E Tech Feedback Loops Plenary: Labor Link, Global Giving, and even the World Bank have put an emphasis on citizen feedback as the core of a new way of doing development.

It’s possible to imagine a world where some of the main reasons for doing monitoring and evaluation are shifted over to citizens themselves – because they want to hold to account both governmental and non-governmental organizations so that the services not only get to the right people, but those people can drive the agenda for what’s needed where.

While a complicated study on, say, the school system and education needs of Kibera people might provide insight, if it sits on a shelf and doesn’t inspire grassroots pressure to shift priorities and improve education, what is the use of it? Why not instead invest in efforts to collect open data on education jointly with citizens, like our Open Schools Kenya initiative?

The benefit here is that the information is open and collectively tended – meaning kept up to date, shared, made comparable with other data sets (like Kenya’s Open Data releases from the government), and used for more than just one isolated study. It’s a way for the community to assess the status of local education itself. In our own neighborhoods and school systems, we wouldn’t have it any other way.

A Citizen Led Future

As noted by Britt Lake of Global Giving on our panel discussion, taking this concept to its logical conclusion there would be a loss of control by development agencies. Is this the real hurdle to citizen-led data collection? To what extent can aid systems be devolved to the people who are meant to primarily benefit?

A truly forward-thinking organization would embrace this shift, because with better information being collected and used at the grassroots, there will be more aid transparency overall and less opportunity for gaming the system. If you think that no small CBO has ever submitted a bogus progress report which went up the chain at USAID, think again.

Nowhere in this system is there incentive to give an accurate account of failures or document intelligent but unpredicted programmatic adaptations and detours that were made. Yet if there’s one thing I know the Kibera people want, it’s for the many organizations they see around them in the slum to be held accountable for all the funds they receive, and for delivering on their years of promises for improving the slum.

In fact, transparency around aid at this hyperlocal level is something we should even feel an ethical obligation to provide. Here’s hoping that in 20 years, the impact of the open data and feedback movements will mean that public information about projects done in the public good is reflexively open and responsive, and M&E as a separate and often neglected discipline is a thing of the past.

This post was originally featured on ICT Works as a Guest Post.