More Riotous Open Data Possibilities of Kerala

Posted: February 4th, 2013 | Author: mikel | Filed under: India | 1 Comment »Theyyam is a religious ceremony of Kerala (from Nila northwards, not in Chalakudy) performed annually and uniquely in hundreds, maybe thousands of temples (see note from Prakash in the comments clarifying..). A kind of possession takes place, the deity inhabits the performer of the Theyyam, through dancing, procession, drumming, fire, psychotropic altered states, elaborate costumes, sometimes sacrifice, all eventually bringing direct blessings, fortune telling, and satisfaction to the place and people in attendance. Superficially, there are similarities in style to other arts of Kerala, like the more refined and somewhat better known art of Kathakali, as well as Mudiyett, recognized by UNESCO as a more ancient source folk practice. We visited the master of Mudiyett, watched his evening instruction of local kids in drumming, and while fascinating, it’s hard in that brief exposure to understand how all these folk art forms fit together and relate to each other. So that’s just one place where I see open platforms for responsible tourism deepening visitors’ experiences by having communities themselves document and share knowledge and draw connections and tell the stories.

Kaleidoscopic Catholic Church in Kerala

Kerala has 75 kinds of bananas, and 75 lakh variations of culture. While we were in Chalakudy, an annual pilgrimage season to a local diety was starting, an intense Hindu bachelor God, which inspired a “temporary temple” in Chalakudy itself (no, I asked, it’s not burned like the Temple at Burning Man). People of different faiths are welcome to celebrate each others festivals, and whether Christian, Hindu or Muslim, the folk festivals all have a similar Kerala feel. There’s blending and borrowing: baroque cake-like churches lit up in kaleidoscopic fun fair lights (again fitting in right on the Playa); the oldest mosque in India nearby in Kodungallur has a Hindu-like oil lamp in the most inner place of worship. Theyyam sometimes involves very pre-Brahmin seeming animal sacrifice, and tribal peoples perform snake possession ceremonies. I can only wonder what kind of festivals were held at the oldest Synagogue “site” in India, since that community has all left for Israel (based on a gravestone marked 1264, though the entire community traces back at least til 3rd century AD).

Malayalam Calendar. Open Thayam could be just one simple hack of Open Watersheds.

Prakash is a passionate, obsessive collector of Kerala culture. He diligently seeks out the locations of athaani rest blocks, marking the ancient trade routes. He’s called on frequently as an expert on Thayam, having collected the location and timing of hundreds of ceremonies. And he’s generous with his knowledge. From what is his private word doc, we could potentially iterate and create a simple site openly sharing the location, timing and details of Thayam. Start just with a single site, Leaflet or OpenLayers with a timeline, sharing this data. Iterate to something db-backed to help Prakash and others manage the collection and update the collection into the thousands (complexly, timings vary slightly each year because of the subtly different Malayalam calendar). From culture, to passion, to data, to openness, to open culture.

The Temple 2010 on Burning Man Earth

The vibrancy, the pervasive creative and sacredness of Kerala, where any group of trees can become a sacred grove, reminds me of Burning Man, and I realize the platform for creating, sharing and connecting of Kerala’s river basins could look a bit like the structure of Burning Man Earth: there are camps (or places in Kerala context), art, events, and people; and means to connect, communicate, share media, and pivot around all these. One idea that bounced around BME were tools to create your own schedule (pre-selection) and record your own experience (via automatically linking GPS traces to places and art and events). The work of Blue Yonder for tourists is based in part around developing itineraries, and I could eventually see itinerary functions directly in that responsible tourism platform. Before our arrival to Chalakudy we received an ambitious itinerary (exhaustively including every identified responsible tourism site) and having a map and idea of how much road travel the days would entail would have helped us prepare as tourists and sealed the memories. Of course, we were there to actually help create that map…

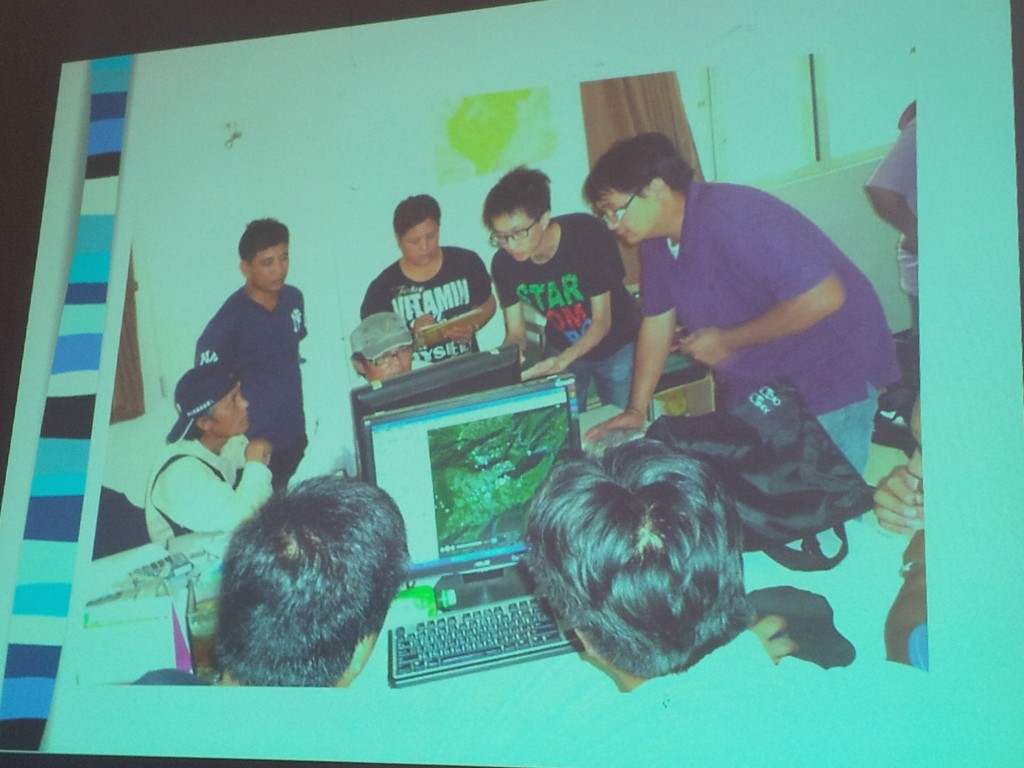

Participatory Mapping of Indigenous Names in Taiwan

Open Watershed Data, and a methodology of responsible tourism for river basins, provides a context for these media tools to develop. Design workshops, data fellowships, (even, um, yes, maybe) hackathons, could enable technical and design participation in creating amazing tools for cultures, communities, environments. Kerala has a volunteer spirit, and people want to contribute to “the something greater” when they have the chance. Folks described as “literary people” research local place names, recording the stories and meanings embedded in those names. While in Taiwan, I sat in on a session with an elder of an indigenous group, while he browsed his village in Google Earth, he told stories of (and a dozen students dutifully recorded) the names of every place, indicating deep knowledge of the landscape, how to practice agriculture, what to expect from the weather, commerating the efforts of the past. Indigenous people of Taiwan have gained stature in their society, and they are working to see through the right to return to indigenous names in their communities, yet the big challenges of responding to change remain, including increasing interest from Han Chinese tourists. The struggle is to maintain the integrity of the culture, preserve the culture, as money comes in, avoiding division and degeneration as more opportunities open up. One tribe managed to organize into a tourist cooperative, so home stays and the like don’t compete but cooperate. Many issues are over the land itself. Do individuals in the tribe have the right to sell land to outsiders for agriculture, even if risking overuse and environmental degredation, as it is their land, or is there a collective responsibility in the notion of tribal rights?

The issues of land rights management, cultural preservation all ring true to Kerala, with overlapping jurisdiction of tribal reserves, forest reserves, water bodies, and individual rights. In Kerala, what to say when the people of the river in some desperation, mine the sand in order to make a little money and survive, yet hasten further destruction of the river they depend on. The last remaining sand bank of Chalakudy was saved due to collective effort, as it was adjacent to a religious site. Hence, culture and value are the greatest strengths to seeing long term benefit vs short term individual gain. Perhaps sharing openly, and inviting the real interest of the wider world, can change the trajectory of damanged rivers and lost ways of life.

There is a tremendous wealth in Chalakudy. The crop of this very place, pepper, drove globalization mellenia ago. Roman coins have been found here. Jewish and Christian communities have been here since the 3 century AD. The first mosque and first synagogue in India are here. Colombus was looking for Chalakudy. The Portugeuse built the first European fort on this river. All of this is smartly being invested in by the Kerala government in the Muziris Heritage project. It’s wonderful, and likely to draw many tourists, both international and from India’s growing middle class (the India tourist riotous take of a place like the Athirappalli Waterfall is an experience in itself). But what of the every day history still there today. There are growing numbers of people who want to know more, surely typical and niche, but a crucial part of the tourism “industry”, or maybe better, “culture”. During our last trip to Nila, we impromptly stopped at a matchstick factory. The ruckus of this very basic mechanical operation was transfixing, totally normal to the people working there, who couldn’t understand our interest … but have you ever seen matchsticks made by hand? Social media and the internet are connecting unprecedently, changing relentlessly, challenging (I heard young Kerala guys listening to Gangam Style on their phones). We’re in that moment where perhaps this force of technology can discover and perserve the extraordinary normal of Kerala.

Chalakudy and River Basin Open Data

Posted: November 24th, 2012 | Author: mikel | Filed under: India | Leave a comment »I’m trying to gather thoughts from our whirlwind spin mapping and documenting through the Chalakudy River Basin with The Blue Yonder friends; and connecting to various other half formed ideas and unprocessed experiences. You might experience a little whiplash through the mental landscape, but no worse than than the twists and turns of Kerala roads…

The last remaining sand bank on Chalakudy River. It remains due to local agitation and proximity to religious sites. The rest have disappeared to sand mining

We have decamped 12 kms from Chalakudy, The Blue Yonder is renting us a hotel room (in five hour increments) to take advantage of the sort-of usable wifi, and crush the last few days of experience and ideas into software, maps and media. Passing by in the streets below is a jeep, flying the hammer and sickle flag, announcing monotonously and over loud-speaker in Malayalam, appointments to various local committees. Prakash is uploading videos and making reports on an Ushahidi instance running locally on my laptop, configured with custom map tiles resulting from another three days of epic drives of Kerala (that platform is now online here. Every responsible tourism spot we’ve visited is being sketched in a report, pictures, videos; and already mapped in OpenStreetMap (tourism=responsible). I’m excited for how many ways openness can share and preserve the amazing culture and environment of the Chalakudy river basin in Kerala. Like everywhere, Kerala faces extraordinary global pressures, and I notice how collective and individual efforts are in an everlasting interplay to protect, undermine, inspire, catalyze, smother, build and destroy these experiences and environments, yet again reflected in the global rush to digitize and connect to the global brain.

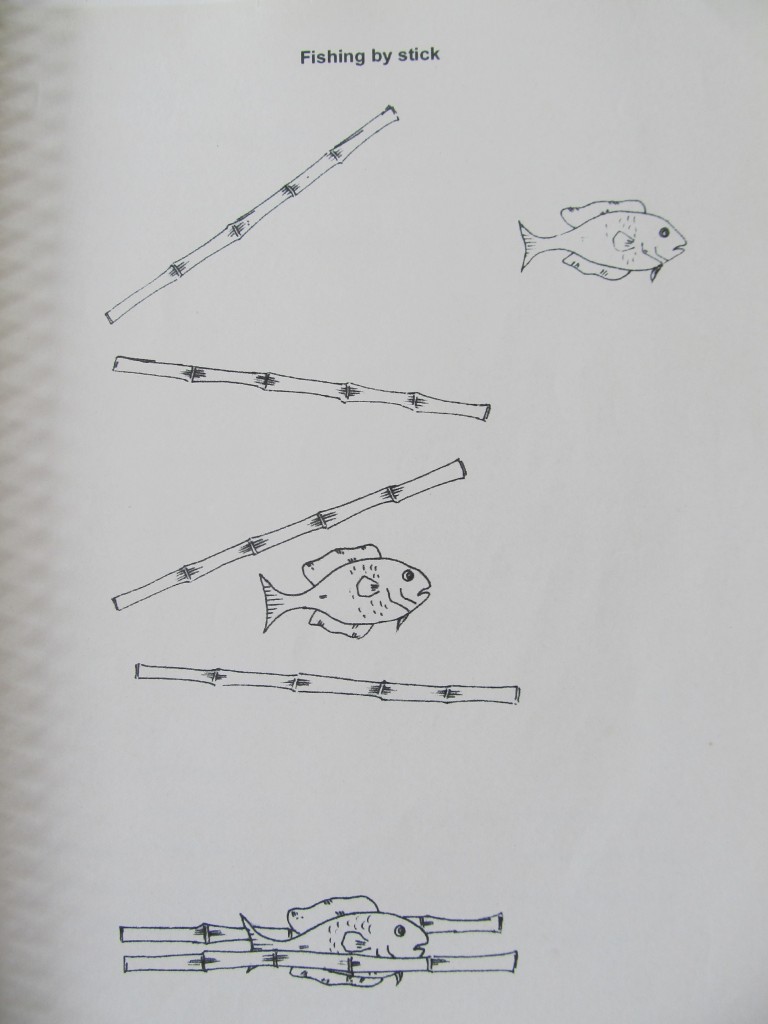

fishing by stick is a reality

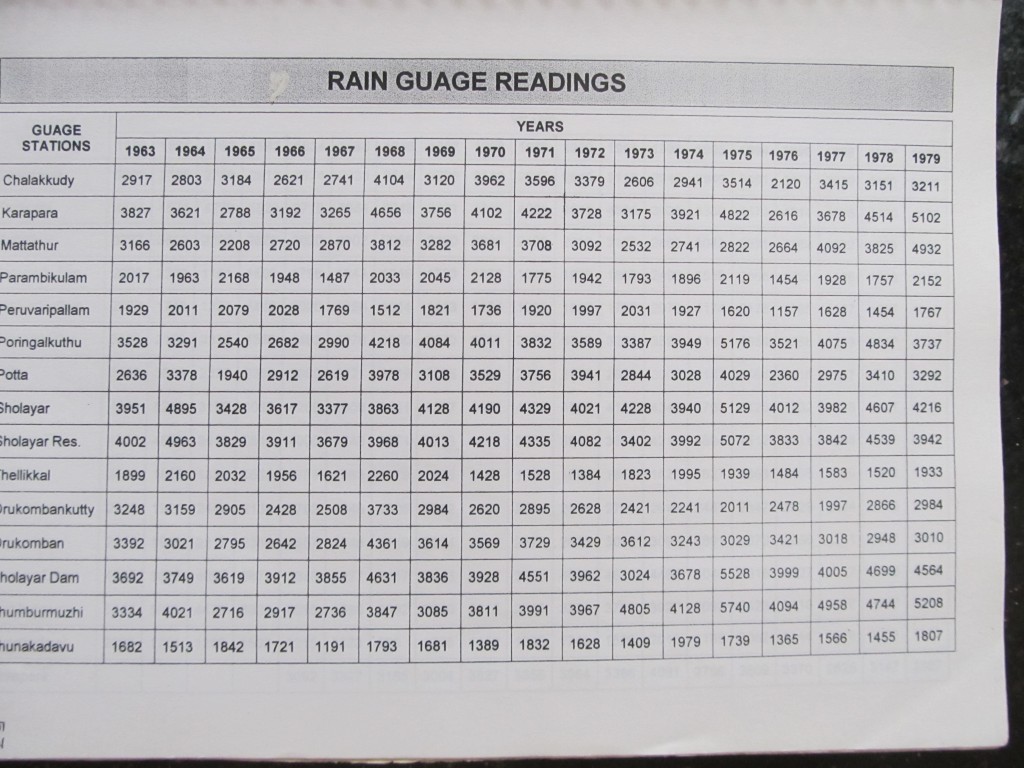

Chalakudy is Kerala’s most wild river, with the highest biodiversity of all Keralan rivers, largely lying within the rugged landscape of a forest reserve. Each morning, with several cups of chai acquired from the road side shop down the way (poured in meter long hand movements by a woman who works every sunlit hour, and many dark ones, except for a half day break on Sunday) (the road is the former tram way built by the British to expedite extraction of virgin teak forests, used among other things for reinforcing N African trenches in WW1), I read through Dr. Sunny George’s epic integrated atlas-like report on the Chalakudy watershed, covering everything from the settlement history and demographics of “scheduled tribes” (as designated in India, indigenous people who have retained their identity and largely way of life through thousands of years of contacts with various ruling structures), to land use changes over the past decades (conversion of rice patties to clay mining or conventional framing, planting of oil palm along river banks, historic exploitation of massive teak forests, and the numerous effects on water flow, retention and livelihood), to pages of tabular data indicating worrying declining flow of the river overall, to the wide diversity of traditional inland river fishing styles (reflecting fish biodiversity, and even including the unbelievable technique of catching fish between two slowly closing sticks). It’s a wonderful primer to understanding this place, and its locked away in 400 loosely bound pages; the floppy disks holding the soft copy have perished to mold sometime in the past 10 years. Its information and data that’s difficult, almost impossible, to share and utilize, yet should be required reading for anyone making decisions about the watershed. Yet it represents only the slightest beginning of the knowledge actively enmeshed in the landscapes and cultures of Chalakudy.

Open Data Watershed

A watershed is a natural ecological and cultural boundary, plainly obvious when you know to look for it. So much of the environment and character of a place, its inter-dependencies and issues, are based not on the numerous and complicated overlap of administrative boundaries (as evidenced by the long list of offices and sources consulted for compiling in the Chalakudy report), but rather the way water flow shapes landscape and human settlement. Cities are a natural organizing principle (though only I learned at Meeting of the Minds a formal focus of study more recently), and have easily grown into the framework of Open Data (also coinciding w/ #motm12, was launched the aggregate city site cities.data.gov). Like cities, open Watersheds can be a movement with real legs, to share environmental data and build on the models of engagement across disciplines evidenced in other Open Data movements. And of course, cities are intertwined with watersheds, traditionally founded on strategic points on rivers. Conceptually, it can easily attract coders, policy makers, scientists, historians, students who have already grasped Open Data; while the watershed is a geographical unit of focus that is tangible and practical. Watersheds are nested, fractal-like structure, so that data can be shared and compared across watersheds of similar scale (through the evolution/conversations of tagging structures/flexible taxonomies) (similarly, in Cairo, Takween and Diane Singerman were developing taxonomies to more easily understand, compare, develop interventions, and support grassroots learning in informal settlements). And watershed data can be generalized to contribute to larger scale models and policy, ultimately to the global level.

The Blue Yonder is developing the idea of design workshops, where experienced and student designers hold a month or two residency with a traditional crafts group in Chalakudy (like the Bamboo Craft workshop) and develop ideas which could be marketable to tourists and abroad (products from the Natural Fibre Craft Resource Center even now is marketed by IKEA). The same could be done for data. A big start would be looking at updating and translating to the web the Integrated Study of Chalakudy. And OpenStreetMap is an ideal platform to model and implement part of an integrative approach. In OSM, land use, water structures, tourist infrastructure are all stored together in a single database, yet seperatable for particular visualization and analysis.

Next couple posts will dig into more how open data and community media complement a responsible tourism approach, leading we hope to a methodology for addressing the issues facing river basins, as well as some more technical ideas and directions.

Kerala exploratory visit

Posted: April 25th, 2012 | Author: Erica Hagen | Filed under: India | Tags: crowdsourcing, cultural heritage, tourism | 3 Comments »In March, GroundTruth went to Kerala, India at the invitation of The Blue Yonder, a “responsible tourism” outfit operating throughout India and based in Bangalore. Not knowing quite what to expect, we nonetheless jumped at the chance to work on a project about crowdsourcing the cultural history of the Nila River. Nila is one of the destinations that Blue Yonder knows best. Its founder, Gopinath Parayil, is a native of the area, which is in the northern part of Kerala state. Prakash Manhapra, another TBY staff, is a lifelong resident of Tirur, a city near Nila, and has absolutely encyclopedic knowledge of the region. Better yet, he has the curiosity of a journalist and an instinct for drawing out a fascinating tale from just about any bystander we came across.

Our task was to take a look at the wealth of cultural activity and history in the Nila basin, much of it very place-specific, and devise a methodology and training for turning this into an engaging multi-input platform for showing off the local riches. This all with a view toward drawing out elements for the tourist to seek out and enjoy, giving locals a chance to celebrate their heritage, while providing a means for preserving not only some of the more fragile customs and artistry but also the very river itself. Besieged by a long-running sand excavation, the “sand mafia†controls an often illegal but overlooked sand mining operation which is quickly destroying the ecosystem of the river linking the fascinating human settlements together over millennia. The hope of Blue Yonder was that the platform would help fight the environmental battle underway by reminding people how interlinked their lives were to this river.

We took a welcome opportunity to use some of the same tools we’ve developed for slum residents to report on basic services and needs, Palestinian activists to share their efforts to retain their land, and Nigerians to share crime and security reports, to the more cheerful topic of highlighting a rich cultural heritage. And Nila has plenty of positive to share, as we discovered. We visited artisans making bell-metal puja sets, handweaving cloth, and throwing clay into cups and bowls in ways that reflected centuries-old traditions. We visited ayurvedic doctors, martial arts practitioners, traditional dance and Kathakali theater, even an all-night shadow puppet performance that is enacted for many nights in a row with or without audience, to please a watching goddess.

There was the unplanned too – we happened upon a tiny village festival featuring frightening fire-theatrics and elaborately made-up ritual performers channeling the snake deity. At another nighttime temple festival a band of drummers played relentlessly and ecstatically for hours until they stopped all together on a dime, leaving a haunting ring in the air for several seconds.

I also got to see elephants. Though some looked a bit sad.

Mesmerized as we were, we got down to business. Developing a system for recording some of these events would not be the challenge; even collecting media might be easy given that everywhere we went we saw cellphone photography and video in process. Kerala is not particularly poor; the historically communist-run state is proud of local development and a small fortune has been sent back from migrants overseas in the Gulf. Building a way for locals to interact would require, yes, a mapping of the area as well as a variety of ways to report through media and aggregate. We also wanted to involve the artisans somehow, so that they would receive more business, and integrate a social interface for recent visitors and tourists to submit media and interact with locals. Of course, the primary language in the area is Malayalam, complete with its own swirly script. Interaction with the site would have to be possible through Malayalam-enabled keyboards, Romanized inputs typically used with mobile phones, and English.

As usual, the wild card would be the community-level participants – who exactly would be energized to report, on what, and who would sustain the enthusiasm? Options included working with a fantastic local group Vayali, already dedicated to exhaustive cataloging of local culture for academic and other purposes, as well as a widespread project of youth engaged in a volunteer palliative care movement. These youth had the civic engagement spirit along with local knowledge. We could also access a mass-media outreach campaign to engage more contributors. Integration with social networking online was also important.

This project sparked a long-dormant passion of mine to preserve and protect traditional social and cultural practices which I believe are in similar (and related) peril to the ecosystems that are being systematically destroyed. There is an interrelation between the attention that one can focus on a cultural feature, and its survival in the face of immense economic and social pressure to conform to the dominant or “modern†culture.

Gopi showed us traditional Keralan architecture, which is being replaced, like everywhere, by cement block ugliness. I sometimes think of how the houses in my hometown were remodeled in the 1950’s to reflect the day’s mores, eliminating all the wood trim and tin ceilings. It’s only now that homeowners are trying to reconstruct what was damaged back then, which is never as good as the original. Gopi has convinced – sometimes by actually offering payment – some owners not to destroy but to preserve the traditional houses, by insisting that tourists would pay handsomely to stay in these beautiful lodgings. Running a tour company, he has some authority to make this claim. Examples of expensive “traditional†lodging abound, usually only as imitations. (Here’s a cool example of architectural preservation and tourism in Kathmandu).

Sometimes, locals do not realize that what they have always had – traditional architecture, artisanry and crafts, medicine and religious festivals – can be extremely valuable to the visitor as well. Of course, there is the danger that such practices will become museum-pieces for benefit of tourists alone. That is something we experienced in Kenya, where safari tours visiting colonial-style lodges will be presented with a song-and-dance performance abandoned by the actual representative tribe years ago. The effect was, for me, disturbingly patronizing. There’s nothing quite like seeing Kenyans dressed proudly in their costume on property once part of their spiritual homeland, in front of white haired foreigners supping on mashed potatoes and corned beef, in a lodge built by British colonials. But I digress.

The amazing thing about Kerala (and other parts of India) was that in no way was any of what we saw put on for our benefit, and yet, a visitor could still inspire pride and represent a financial incentive to support certain elements of culture. With our system, we hope to expand that experience to reporting oral history, heritage, cuisine, and other aspects of the river culture that make the place all that much richer. For example, there are archaeological remnants of an old trading route that tied into coastal shipping routes, pit-stops called Athaani that traders used to use for rest and refreshment, which we hope to map and annotate with interviews along the way. Only it won’t be us – as usual, only the community members will contribute, no outsiders, no researchers, no foreigners or even local city-folk. That kind of process, I hope, will lead to local ownership not only of this technology but also of the Nila itself.

Unpacking Bangalore’s Tech Activist Scene

Posted: March 30th, 2012 | Author: mikel | Filed under: India | Leave a comment »Erica Geeked Up in Bangalore, and give a talk “From Information to Empowerment: Unpacking the Equation”.

Nice to follow in the footsteps of Hapee’s GeekUp on OpenData.

The talk surveyed our work with GroundTruth, in community mapping and media, in Kibera and elsewhere. Got a nice write up in The Hindu. And a reprise with the warm and progressive parents of the Earth School Montessori school.

In between, Erica attempted to sweep through and catch up with as many of the interesting movers in Bangalore. Finally got to meet in person with IT For Change, who were among our collaborators on the IDS research project Mediating Voices, Communicating Realities, and are particularly interested to see how participatory mapping and media can apply in rural settings.

Sridhar Pabbisetty, from the Center for Public Policy at IIM Bangalore, welcomed Erica for a talk and time with his students. And also, facilitated a visit with CHF’s slum improvement projects in Bangalore.

Another highlight was meeting with Jaanagraha, the group behind the amazing I Paid a Bribe. A key component of the strong anti-corruption movement in India, and now inspiring similar efforts worldwide, was very instructive to hear how this campaign took hold.

An intense few days … felt deep, and yet just scratching the surface. So much more to loop together next time in the Bangalore tech activist scene!

Cartonama, Open Mapping in Bangalore

Posted: March 29th, 2012 | Author: mikel | Filed under: events, India, talks, tech | Leave a comment »The keystone to GroundTruth’s trip to India was the Cartonama workshop in Bangalore.

My comrade in maps was the amazing Schuyler Erle, in a reprise of our epic 2008 Free Map India tour. India, Banalore, and its OpenStreetMap have transformed (as you can see in this heart-filled animation of OSM Bangalore). This time, rather than visit 7 cities in 4 weeks, we crammed even more information into two days. As ever, I learned a ton from Schuyler. Perhaps the choicest bit being, “Canada is often projected as if the Earth was wearing a dunce cap”.

This was an intense two day workshop, covering everything needed to make an open web mapping application: from data collection in OpenStreetMap, to data juggling with OGR/PostGIS etc, making tiles with TileMill, and finally building an Ajax Web app with Leaflet and the OSM API. Oh, and also a survey of basic geographic concepts (geodesy, projections, etc), and the intricacies of the operation of GPS satellites. Really it was four workshops in one. Or maybe 10. Possibly a semesters worth. I think it’s a format worth replicating.

The end result was a modification to the amazing POSM POSM by Yuvi Panda. He built this HTML5 web app for first collecting bus stops in Mumbai. There were wonderful audible gasps when we integrated our home baked MapBox tiles into the locally running POSM app (even if we discovered lingering problems with handling of Indic fonts in Mapnik).

You can see all the presentation materials on GitHub. We collaborated on the slides in Markdown with Landslide, best way to make a presentation.

Cartonama was an Editor’s Pick in TimeOut!

Another great moment, during the ice breaker we stole from Gunner: “What’s your first memory of a computer?” “We had to take our shoes off before going in the lab because computers are holy, right?”

It seemed to go well. Was great to enthusiastic, creative participants from Servelots, TacticalTech, IT For Change, Transparent Chennai, and many others.

HasGeek did a wonderful job bringing bringing the workshop together, and are lighting up the geek event space in India. They’re really fostering community in the best way, and I’m excited to see what happens with all the mappers from our workshop, and the upcoming full Cartonama conference. So big thanks to HasGeek, and the Centre for Internet and Society for hosting and sponsoring the workshop.